The term techno-nationalism may be of recent vintage, but the idea has been around for more than two centuries. It first took form in 18th century Britain during the Industrial Revolution, when the state imposed tight restrictions on the export of advanced machinery and barred skilled artisans from emigrating — ensuring that its technological edge remained a source of national strength. Japan, during its period of isolation, adopted similar strategies to industrialise rapidly while shielding its innovations.

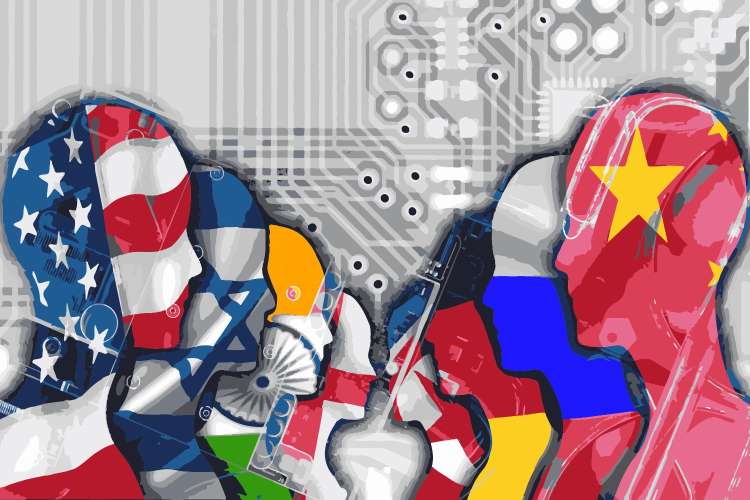

The concept took clearer shape during the Cold War, when the United States and the Soviet Union engaged in parallel races across space, defence, and computing. Government-led research and development, restrictions on technology exports, and competing visions of global technical standards all defined that era. What was once a policy tool to retain economic edge and political dominance is now being revived with renewed urgency — most visibly in the escalating confrontation between the US and China.

READ I Swadeshi revival meets Trump tariffs, trade war

Return to state-led protectionism

In the past decade, governments have begun to reassert themselves more aggressively in strategic sectors. State subsidies, public funding, export controls, and investment screening have become standard tools for shielding critical industries. These interventions often target technologies deemed essential for economic resilience and national security, such as semiconductors, artificial intelligence, and rare earth materials.

Supply chains — once optimised purely for cost efficiency — are now being redesigned for redundancy and resilience. Inventory buffers, supplier diversification, and restrictions on data and talent flows are all part of the new industrial logic. This strategic decoupling, once dismissed as improbable in a globalised economy, is now mainstream policy among major economies.

The battle over technological self-sufficiency is not theoretical. China, for instance, has since 2010 weaponised its dominance in rare earth minerals — essential for electronics, defence, and renewable energy industries. A telling moment came when it halted exports to Japan during a maritime dispute, demonstrating how trade in critical inputs could serve geopolitical ends.

China’s strategic dominance through control

China’s growing assertiveness has extended beyond raw materials. In 2013, it tightened environmental norms for rare earth producers, pushing many smaller firms out and enabling the state to consolidate control. Even as the World Trade Organisation challenged China’s export quotas, Beijing maintained a firm grip through licensing and regulatory barriers.

Its 2017 Cybersecurity Law further extended this control to data, mandating that firms store key information within China and undergo vetting before transferring data abroad. The law also increased scrutiny on imported network equipment and reshaped digital infrastructure rules in ways that disadvantaged foreign firms.

The latest salvo came in 2023, when China imposed export restrictions on seven rare earth elements and high-performance magnets, citing the need to establish a new licensing regime. While framed as regulatory housekeeping, the move had the clear effect of tightening China’s chokehold on global supply chains.

These are not marginal capabilities. Chinese firms control roughly 85% of the rare earth processing chain and 92% of magnet manufacturing. In other critical minerals — graphite, manganese, cobalt, nickel, and lithium — China commands between 60% and 90% of refining capacity. Western mining companies have accused Beijing of dumping excess supply to depress global prices and render non-Chinese competitors unviable.

Semiconductors and the new tech war

The most acute expression of techno-nationalism is the global fight over semiconductor chips. Once seen as mere components, semiconductors are now viewed as strategic assets. The United States has imposed sweeping export bans on advanced chip technologies and lithography equipment, with the aim of stalling China’s progress in AI and supercomputing. China has retaliated with export controls on gallium and germanium — key inputs in chipmaking.

The ripple effects extend well beyond the two rivals. European regulators, wary of Chinese firms dominating the EV supply chain, are tightening scrutiny of foreign investments in automotive and battery technologies. Just a decade ago, China was a minor player in chips. Today, it is racing to close the gap with US, South Korean, and Taiwanese firms.

The global battle for standards

Control over production is only one theatre of this conflict. Another is the battle for influence over global standard-setting bodies. Western officials have grown increasingly uneasy as Chinese companies gain leadership positions in organisations like the 3rd Generation Partnership Project, which sets communication standards for technologies like 5G. Firms such as Huawei and ZTE now chair or co-chair several key technical committees, leading to friction over the shaping of protocols and definitions that will underpin future innovation.

Western countries see this as a dilution of their influence and a strategic risk. The response has included efforts to revive participation in these forums and invest more heavily in technical expertise to match Beijing’s deep bench of engineers and negotiators.

Rebuilding technological sovereignty

The revival of techno-nationalism has triggered differentiated responses across countries. The European Union, for instance, has embraced the language of technological sovereignty and is cooperating more closely with the United States under the umbrella of the EU-US Trade and Technology Council. The European Chips Act is channelling funds into domestic chip fabrication, while parallel investments are being made in AI and quantum technologies.

Japan and South Korea, leaders in advanced manufacturing, are investing in domestic capacity and diversifying imports to hedge against geopolitical risk. India, meanwhile, is positioning itself as a third pole. Under the “Make in India” and Digital India initiatives, it is trying to build end-to-end capability in emerging technologies like 5G, AI, and cyber defence—reducing its reliance on both China and the West.

The contours of the new global order will be shaped less by trade liberalisation and more by strategic competition over technology. China’s use of export controls, industrial policy, and regulatory power reflects a deliberate effort to reorder global trade flows and cement long-term dominance in critical sectors.

The rest of the world is responding in kind, recalibrating supply chains, raising barriers to foreign technology, and accelerating investment in indigenous innovation. As techno-nationalism reshapes policy frameworks, the idea that technology is a neutral force for shared progress is being steadily replaced by a more contested, geopolitical view.

Technology is no longer merely a driver of economic growth. It has become the frontline of national strategy.

Shikha Bhakri is a research scholar at Indian Institute of Foreign Trade, New Delhi.