Rice export ban explained: Amid the unfolding disruptions in the global supply chain, the Directorate General of Foreign Trade has taken the decision to impose restrictions on the export of non-basmati rice from India. The export regulations for non-basmati rice have undergone frequent changes, particularly after the Russia-Ukraine conflict, which created pressures on commodity prices in the international market. Given that India holds a significant share of 40% in the world rice market, this policy intervention has stirred significant attention in the global market.

Western media outlets, in particular, have been vocal, offering moral lessons and advocating for righteousness and virtue in policymaking and execution. It becomes crucial to delve into the local and global factors surrounding this situation to comprehend the underlying political and economic dynamics behind the rice export ban.

Policy decisions concerning restrictions on internationally traded goods are made in consideration of global demand, supply, and other fundamental factors. In this scenario, various fundamental factors have played a pivotal role in disrupting the balance between demand and supply, necessitating this reactive policy decision. These factors can be categorized as systematic and systemic.

READ I Volatile global prices, climate change threaten another round of food price shocks

Systematic factors behind rice export ban

Multiple systematic factors contributed to the rice export ban, with a significant one being erratic rainfall patterns. Key rice-producing states like West Bengal, Eastern Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Chhattisgarh have experienced suboptimal rainfall, with some areas facing a deficit as substantial as 44%. Conversely, states like Punjab, Haryana, and Western Uttar Pradesh have encountered relentless rain, leading to floods that destroyed cultivated crops. Consequently, there has been a delay in planting crops in these vital producing states, resulting in concerns about suboptimal rice production.

Furthermore, cropping patterns have shifted over the past few years, as farmers in Punjab, Haryana, Uttarakhand, and the Terai region of Uttar Pradesh have shown a preference for basmati rice over non-basmati varieties. This shift could impact the overall production of non-basmati rice, raising worries about food availability for marginalized sections of society and even for public distribution through food security provisions. Beyond this, economic factors like population growth, rising per capita income, changing consumption patterns due to urbanization, redirection of surplus production for ethanol under the E-20 program, escalating oil and fertilizer prices, and inadequate investments in agricultural R&D further challenge the situation in India’s agricultural sector.

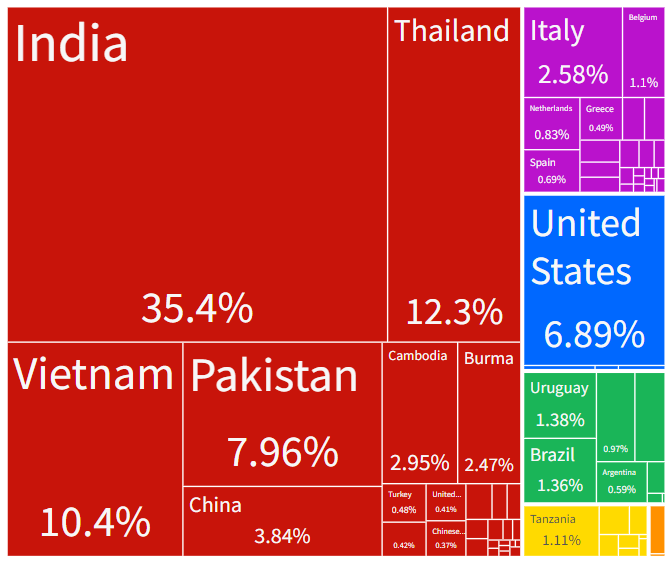

Largest rice exporters

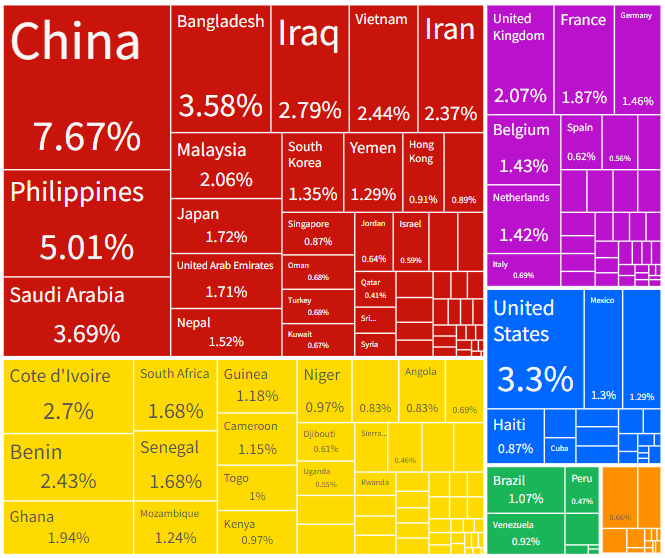

Largest rice importers

The global disruptions in supply chains have resulted in high inflation, particularly affecting staple foods. This price surge has raised concerns for the government, given its adverse effects on the economically disadvantaged, a crucial segment of India’s electorate. Another noteworthy anomaly is the substantial gap between wholesale and retail prices of key staple crops, creating disincentives for both producers and consumers. This gap could be attributed to rampant speculation amid global food uncertainties and inefficiencies within the distribution chain intermediaries.

Nevertheless, considering the available stock, kharif (monsoon season) production, and reasonably strong supplies of alternative foods like wheat, maize, and other cereals, India stands in a robust position to meet domestic demand. Hence, the systematic factors related to demand and supply do not stand out as the primary drivers behind the ongoing export restrictions on rice.

Systemic Factors: The prohibition on rice exports is primarily a response to the evolving geo-economic landscape, shaped significantly by the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Russia’s decision to withdraw from the ‘UN food deal’ has triggered disturbances in the global food market, adding pressure to the already strained global commodity market, compounded by the aftermath of the pandemic and escalating prices of global oil and fertilizers.

Together, Russia and Ukraine contribute over 25% of global food demand. This circumstance prompted commodity speculators to establish numerous letters of credit with Indian suppliers. Faced with a lack of wheat and maize supplies, these speculators turned to stockpiling India’s rice in Free Trade & Warehousing Zones at strategic logistical hubs, including Jebel Ali (Dubai), Alexandria (Egypt), Haifa (Israel), Tema (Ghana), and Calabar (Nigeria). This surge in commodity speculation, coupled with the intent to hold stocks for future lucrative sales, raised alarms among India’s top policymakers, prompting the need to curb such tendencies.

Consequently, this development triggered a ripple effect in global food markets, compelling key suppliers to adopt protectionist measures. The resultant scarcity, combined with the appreciation of the US Dollar, raised alarming concerns about the accessibility and affordability of food, especially in Global-South countries. Indian policymakers acknowledge that low-income countries in Africa and the Middle East are primary importers of Indian rice. Therefore, the speculative practices and stockpiling by Western commodity firms could potentially hamper India’s ability to meet the genuine needs of these countries.

Considering India’s moral and ethical obligations to cater to both domestic and international markets, the decision to restrict non-basmati rice exports is deemed suitable. This rice export ban implies that India will continue to fulfil the specific requirements of Global-South countries under a quota regime. Consequently, the export restrictions are considered a fitting measure to honour India’s just, lawful, and well-intentioned international commitments by providing sustenance to its counterparts under the quota system, while also countering the speculative trading pursued by Western commodity entities.

In this context, the political economy behind the rice export restrictions transcends India’s borders. This phenomenon is predominantly driven by global supply chain disruptions stemming from geostrategic rivalries and vested interests of major global powers. The purpose of these restrictions is to instil order, transparency, and a sense of responsibility in meeting the legitimate economic needs of Global-South counterparts. India has historically and will continue to honour its international obligations while prioritizing its domestic imperatives. However, for the long term, a gradual and incremental approach to implementing such restrictions is recommended, ensuring India’s reputation as a dependable provider of global public goods within a stable, equitable, and foreseeable export regime.

(Dr Ram Singh is Professor, Indian Institute of Foreign Trade, New Delhi.)