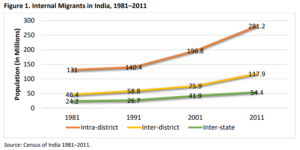

Around 456 million Indians, accounting for 37% of the country’s population, are on the move, according to the 2011 Census. UNESCO (2013) and ILO (2020) estimates indicate that internal migrants directly contribute 10% to the country’s GDP, serving as the backbone of several sectors. Consequently, heated discussions are going on to formulate effective policies covering occupational health, safety, and social security of inter-state migrant workers.

Over the past six decades, Kerala has seen a steady influx of migrant labour. According to NSSO 2020-21 data, Kerala ranks fifth (30.6%) among states that receive migrant workers. The 2011 Census reports that West Bengal ranks first in terms of the number of migrant workers to Kerala, followed by Assam, Bihar, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, and Manipur. A 2021 estimate by the Kerala Planning Board pegged the population of migrant workers in the state at 3.4 million.

Additionally, the 2023 findings of the SERB project “Effect of Social Institutional and Technological Interventions on Access to Healthcare Among Interstate Migrant Labourers in Kerala” identified as many as 80 job categories for migrant workers in Kerala, with daily wages ranging from Rs 500 to Rs 1400.

READ I Partition’s hidden scar: How mass displacement crippled healthcare in India

The pull factors

What makes Kerala one of the most preferred destinations for migrant workers? Extensive field surveys conducted in 40 villages across five districts of West Bengal by the SERB project revealed favourable socio-cultural conditions, availability of adequate educational opportunities, and higher minimum wages as the prominent factors attracting migrants to Kerala.

The significant growth in the construction sector, coupled with the absence of natives in traditional sector workforces and their refusal of unskilled jobs due to expanding educational attainment, suggests that the future of Kerala belongs to migrant workers.

In response, Kerala has rolled out a host of social welfare schemes for ‘guest workers,’ including the Migrant Welfare Policy (2010), the Awas Insurance Policy (2017), the Apna Ghar Residential Scheme (2019), and fourteen literacy and educational schemes, including the flagship ‘Hamara Malayalam’ programme.

The integration challenge

What sets these efforts apart is that while other states try to situate their policies for inter-state migrant workers within the obligations of the Inter-State Migrant Workmen Act 1979, Kerala has innovated schemes that go well beyond welfare to the holistic development of migrant workers and their families.

It is worth mentioning that although states such as Jharkhand (Shramdan), Karnataka (Seva Sindhu Portal), Odisha (Shramik Sahayatha), and West Bengal (Karmasathi) have devised innovative schemes for the health, welfare, and security of migrant workers, they are still considered de facto citizens in these and other states. According to the Interstate Migrant Policy Index (IMPEX) Report 2019 by the NGO India Migration Now, Kerala emerged as the most migrant-friendly state, with indicators on child rights protection, education, health, and sanitation highlighted.

The integration crisis

A study by the Centre for Migration Policy and Inclusive Governance at Mahatma Gandhi University, Kerala, on the increasing instances of migrant workers becoming victims of intolerance, revealed a spike in fake news and narratives against them in Kerala’s news and social media forums. The rise of xenophobic tendencies in local newspapers and social media platforms has made migrant workers feel insecure in the state.

The recent lynching incidents of Rajesh Manji, a native of Bihar, and Ashok Das from Arunachal Pradesh, though isolated, highlight the urgent need for discussions on the insecurity faced by migrant workers in Kerala’s public discourse and concrete efforts to integrate them into society for harmonious coexistence. While violence perpetrated by migrant workers generates negative sentiments against them in Kerala, it is imperative for the government to determine how safe, orderly, and regular migration, as envisaged in the UN Global Compact on Migration (2018), can be realised. The necessity for a comprehensive immigration policy is evident here.

Policy suggestions

Based on field studies across all 14 districts of Kerala and extensive discussions with policymakers, the following policy recommendations are suggested for government consideration:

Registration of migrant workers and their health and welfare services are centralised under the Kerala Labour Commissionerate. This has often resulted in beneficiaries not receiving adequate and timely information regarding their rights and entitlements. Implementing a decentralised data collection and dissemination system through local self-government institutions would bridge this crucial information gap.

Each panchayat should be empowered to impose a monthly working tax on interstate migrant workers while ensuring systematic registration, accommodation, sanitation, health, and legal services for tax-paying migrant workers. This would provide the government with thematic information beyond mere numbers.

Interstate agreements for data exchange would help identify workers with criminal backgrounds in destination states and secure their social welfare and legal protection in source states.

Efforts to ensure the inclusion of migrant workers in institutional mechanisms need to be bolstered. The government should provide necessary documents to those workers wishing to settle permanently in Kerala. Domicile certificates should be issued to migrant workers residing in the state for the past five years, giving them access to institutional benefits and processes, including elections. Public employment and higher educational opportunities should also be available to the children of migrant workers through education subsidies.

A unique health model encompassing universal coverage should be conceived based on best practices from existing schemes. Primary health centres/ community Health centres should conduct free medical camps exclusively for migrant workers and their families monthly. Mobile medical units should be deployed to provide medical aid to remote areas. Compulsory service of doctors in primary health centres during night hours should also be ensured.

Transparency in the allocation and utilisation of resources provided by the Union and state governments must be ensured by subjecting the accounts of various schemes concerning migrant workers to social auditing.

As interstate migrant workers continue to become the primary labour force in Kerala, the onus is on the government to craft policies to accommodate their influx and integration into Kerala society.

(Navas M Khadar is Project Associate, GoI-DST-SERB Project, Mahatma Gandhi University, Kottayam. Anjali J is Research Intern, Centre for Migration Policy and Inclusive Governance, Mahatma Gandhi University, Kottayam.)