Kerala economy at a crossroads: Sri Lanka and Kerala have striking similarities in terms of agro-climatic conditions, structure of economy and human development indicators. Now with Sri Lanka facing a major economic crisis, it is natural that people are speculating about the future of Kerala’s economy. While Sri Lanka is an independent country, Kerala is a sub-national unit within a federal country. However, Kerala can learn a lesson or two from the ongoing crisis in Sri Lanka.

There is a widely held perception that the present crisis in Sri Lanka is the fallout of huge borrowings from countries like Japan and China for mega infrastructure projects. While this is one of the reasons for the present crisis, a deeper analysis would show that a host of factors are responsible for the Sri Lankan meltdown.

READ I Tracing Sri Lanka economic crisis to mindless liberalisation, fancy projects

The making of Sri Lankan crisis

For one, Sri Lanka has been experiencing slower economic growth for the last 10 years. But the situation took a turn for the worse when Gotabaya Rajapaksa came to power in 2019. The structural specificities of the economy, the Covid-19 pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine war, and some policy measures taken by the government can be blamed for the crisis in varying degrees.

Like in the case of Kerala, the main pillars of the Sri Lankan economy are tourism industry, remittances from expatriates, and foreign exchange earned through the export of agricultural products like tea. Income from tourism had started dwindling after the Easter terror attack in 2019, and it acquired alarming proportions after the Covid-19 pandemic broke out. Remittances from expatriate Sri Lankans also fell significantly during this period. Some of the ill-advised policy measures like switching over to organic farming by completely avoiding the use of chemical fertilizers resulted in a steep fall in agricultural production and export earnings from tea.

The policy blunders committed by the Rajapaksa government added to the crisis. The government announced tax cuts and several measures to make the country business-friendly ahead of the 2019 elections. On winning the elections, the government reduced VAT from 15% to 8% and Nation Building Tax from 2% to 0%. As a result, government revenues fell from $10.9 billion in 2017 to $6.6 billion in 2020.

READ I Kerala Budget 2022-23 will struggle to fund its vision

With the revenues from internal and external sources drying up, the government had to rely on borrowing to meet the mounting expenditure necessitated by the Covid-19 pandemic. Import of essential goods including food items, fuel and medicines shrank after the foreign exchange reserves hit rock bottom. Now the country is in the grip of galloping inflation, causing a severe shortage of essential goods.

It is not the external debt, but the crumbling domestic economy that deepened the Sri Lankan crisis. Putting all the blame for the Sri Lankan crisis on external borrowings may be barking at the wrong tree.

The lessons for Kerala economy

What are the takeaways from the Sri Lankan crisis for policymakers in Kerala? There is a view that there are not many implications for Kerala as it is just a state within a country. This may be simplistic, considering the fact that the root causes of Sri Lanka’s crisis are present in Kerala’s economy as well. Kerala is in the process of availing massive foreign assistance for its flagship semi-high-speed K-Rail. Kerala is already one of the highly indebted states in India.

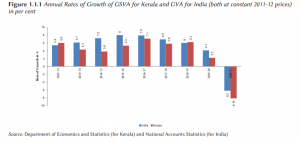

As per the 2022-23 Budget estimates, the total liability of Kerala will be Rs 3,78,476 crore by the end of March 2023. Of course, Kerala’s debt is within the limits imposed by the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act. Comparing Kerala’s debt-GSDP ratio, some economists have said that it is not as alarming as it is made out to be. A better indicator would be the capacity of the state to service the debt when it is due. According to renowned economist Evse Domar, so long as the rate of growth of an economy is higher than the prevailing interest rate, debt need not be a cause for concern.

The underlying logic of this proposition, known as Domar Gap, is that borrowed funds are utilised for growth-promoting investments which, in turn, lead to higher tax revenues to service the debt. When it comes to Kerala, one cannot be but a little circumspect about growth prospects. Like Sri Lanka, Kerala has also learned how fragile sources like expatriate remittances and tourism are.

Two disquieting aspects in the growth dreams of Kerala are the ageing population and climate change. First, Kerala is fast-becoming a big old age home, according to demographers. The number of people above 60 years of age will be around 20% by 2025. Taking care of the aged population is going to be a big burden for the state exchequer. This also means that the number of young people who will migrate and bring in remittances will decline.

An increasing preference is visible among young migrants to settle down in countries where they have migrated. Second, compared with most Indian states, Kerala is more vulnerable to threats of climate change like floods, tsunamis and drought. This suggests that Kerala has to be cautious about a high debt burden. It may be argued that in the event of a crisis, the Centre will bail out the state government. The Centre is bound by constitutional provisions relating to sharing of federal resources.

The main function of the Finance Commission, the constitutional agency mandated to distribute federal resources between the Centre and states, is to ensure that more public resources flow to states which are lagging behind in basic public services. This means that Kerala, which is far ahead of most Indian states in human development indicators and physical quality of life indices, will have to come to terms with a progressive fall in Central transfers in the years to come.

For a moment, assume that investments in infrastructure projects like the K-Rail will lead to high growth. Will it translate to high revenues? Kerala’s experience in public resource mobilisation for the last 65 years makes one pessimistic. During the first 10 years of Kerala’s formation (1957-68 to 1966-67), Kerala’s share in own revenue mobilised by all the states put together was 4.45%. In 2019-20, this share has fallen to 4.34%.

Does this mean that the capacity of Keralites to contribute towards public resources registered a fall? Of course not. In fact, Kerala experienced a phenomenal increase in fiscal capacity. The state stood at the 8th position in per capita household consumption in 1972-73. Kerala climbed up to the 3rd position in 1983 and to the 1st position in 1999-00. What is more, Kerala mobilises over 60% of its own revenue from 4 sources – liquor, lottery, petrol, and motor vehicles. A significant portion of this income is drawn from the poor and the marginalised.

Kerala’s poor fiscal performance is the direct fallout of its heavy dependence on borrowing which has created the mindset that the government will somehow manage its affairs. A society long-accustomed to light fiscal burden cannot be easily convinced to contribute to public purposes. Tax-paying culture is something that a society inculcates over decades. It is increasingly becoming difficult to raise tax rates or introduce new taxes in Kerala.

Almost 67% of borrowed funds are utilised for revenue expenditure. In order to overcome the FRBM limits, the state has floated off-budget borrowing arms, Kerala Infrastructure Investment Fund Board (KIFBI) and Kerala Social Security Pension Ltd. Though the borrowing by these agencies is outside the budget, the repayment is from budget revenue. These contingent liabilities have added to the overall debt burden of the state.

The moral of the story is simple – the Sri Lankan crisis should serve as an eye-opener for the political class and civil society in Kerala who seem to be carried away by the hype around the K-rail and its potential to transform Kerala into a knowledge economy.

(Dr Jose Sebastian is a former faculty member of Gulati Institute of Finance and Taxation, Thiruvananthapuram. Views expressed are personal.)