Need for gender-responsive transportation planning: Indian cities are witnessing a striking disparity in the way men and women travel. Women often exhibit what can be termed a mobility of care, engaging in more journeys associated with non-work-related travel, unpaid household duties, and caregiving responsibilities. Their journeys tend to be shorter and spread across various locations, mainly due to their employment in informal sectors which are typically away from the city centre. Women frequently combine paid employment with unpaid care work, creating interconnected trip chains to manage their diverse responsibilities. On the contrary, men’s commutes generally involve longer distances, as they are more often employed in formal, centralised sectors located in city centers and industrial zones.

A recent study conducted in three cities — Gaya, Patna, and Muzaffarpur in Bihar —- has shed light on the significant challenges faced by women in India. This primarily relates to the issue of limited mobility of women, which diverges from the international trend where women are making more trips. Household surveys unveiled that women undertake 37% fewer trips than men, opting for more sustainable modes of transportation, including public transport, intermediate public transport, or walking.

READ I India’s ageing population presents challenges, opportunities

Need for gender-responsive transportation planning

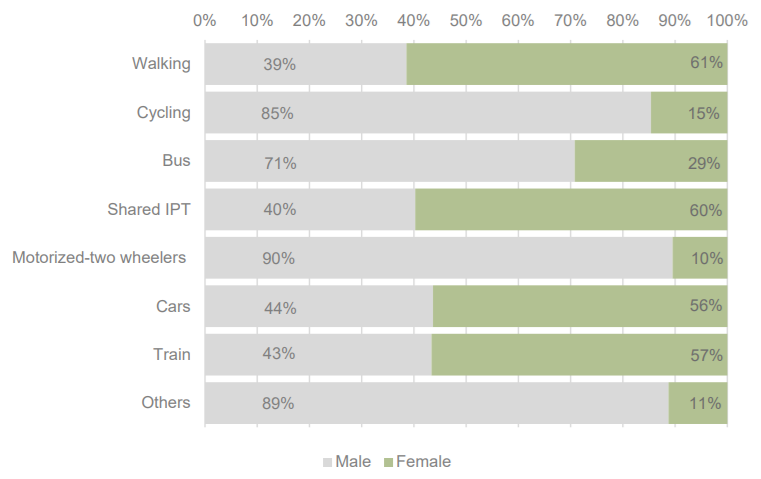

Women constitute 60% of all walking trips. In the case of intermediate transportation which accounts for 20% of all trips, an overwhelming 60% of users are women. While these findings pertain to tier-2 cities, where data availability is limited, it is reasonable to expect similar trends in tier-1 cities, given women’s preference for more sustainable transportation methods.

While urban transport planning may appear inclusive on the surface, designed to cater to everyone’s needs, it often falls into the trap of offering one-size-fits-all solutions, inadvertently constraining women’s mobility. This constraint, in turn, hampers their socio-economic growth because mobility is not just about moving from one place to another; it is also about creating opportunities.

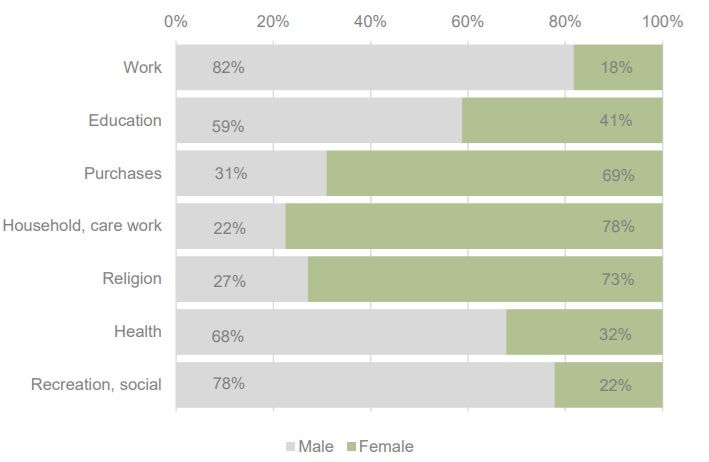

Travel purpose by gender

Travel modes by gender

A significant portion of formal sector employment is occupied by men, whose jobs are predominantly located in and around the city centres. These workplaces are easily accessible as they are usually situated in areas well-connected to public transport. Men’s journeys often span the city, commuting from the outskirts to the city center for work and then back home. Since men primarily use public transport during peak hours, the public transportation systems are also designed to effectively operate during these times, efficiently catering to the needs of these formal sector workers, aligning with the travel patterns of men commuting to work.

In stark contrast, less than 20% of women find employment in the formal sector. The majority of women employed in the informal sector travel to workplaces during off-peak hours, often located on the outskirts of the city. However, their story extends beyond their workplace; women aren’t just employees; they are conductors of a complex family structure. Many begin their workday after men have left for their jobs and well before their children return from school. During these off-peak hours, public transport becomes less frequent, extending wait times for these female commuters.

Examining the statistics more closely, while work-related journeys constitute a significant 41% of all trips, only 18% of these trips are undertaken by women. The current urban transportation system primarily serves the needs of male commuters, operating on schedules aligned with the daily routines of formally employed men. A study in Bihar by Urban Catalysts uncovered a stark reality: a staggering 73% of women’s trips are linked to household chores, caregiving responsibilities, and essential errands, primarily during non-peak hours.

The mismatch between public transportation schedules and women’s needs often compels them to choose costlier alternatives such as auto-rickshaws. This holds true even in places where public transport is free for women, as seen in Delhi. Public buses struggle to accommodate the distinct travel patterns of women due to variations in peak hours.

A survey conducted across three cities in Kerala -— Ernakulam, Kozhikode, and Trivandrum -— by Urban Catalysts and GIZ uncovered a startling statistic: 74% of young girls aged 18-20 experienced sexual harassment, often compelling them to limit their journeys, especially after 7 pm. Even women working in the transportation sector have to deal with safety concerns. Female e-rickshaw drivers, for instance, often avoid seating male passengers in the front seat due to harassment fears. This gender-based limitation results in these female e-rickshaw drivers earning approximately 25–30% less than their male counterparts, despite covering similar distances.

Safety concerns and incidents of harassment impacting women’s mobility have a far-reaching impact on their access to education and economic opportunities. Limited mobility affects women’s ability to access education, employment, and essential healthcare services. To navigate this challenging landscape, women often resort to strategies like traveling in groups, further constraining their access to education and employment opportunities. This also encroaches on their personal freedom.

It is imperative to transform this narrative of gender disparity into a story of inclusivity in urban transportation. The solution lies in giving priority to gender-responsive transportation planning. To effectively address the challenges in urban mobility for women, we must collect and analyse user data that includes women, men, transgender individuals, and those of other genders. This critical initial step lays the foundation for creating public transportation systems that accommodate the unique needs and travel patterns of everyone.

Additionally, we can enhance safety for women by increasing the number of staff in the workplace. An inspiring example is the Kochi Metro System, where 80% of the staff is female, making it easier for women to commute even at night without worrying about safety concerns. To address the issue of public buses being unable to accommodate women not employed in the formal sector and with other responsibilities, we should establish certain guidelines to ensure that buses should also operate with a higher frequency during off-peak hours.

Gender-responsive transportation planning isn’t a luxury; it’s a necessity for cities. There is a huge scope for improvement in our existing transportation planning that neglects the needs of women, making it harder for them to access education, jobs, and economic independence.

The city administration and state governments have to come up with robust plans to understand women’s travel patterns and safety concerns. This can also include collecting actual data from the concerned group that can help them incorporate better implementation strategies. Investment in safer, more accessible, and women-friendly transportation can empower not only women but can also vastly improve the health of public transport for everyone.

(Sanobar Imam is Research Associate with CUTS International.)