India’s growth narrative is often told in the language of GDP projections and digital adoption rates. But beneath the celebratory data lies a deep contradiction: a stubborn gender gap in workforce participation that continues to limit the country’s economic potential.

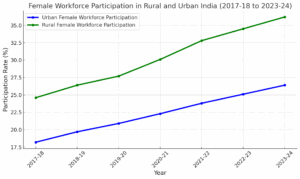

According to the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) 2022–23, 75% of Indian men are part of the workforce, compared with just 37% of women. While this marks a notable rise from 23% in 2017–18, the gender gap remains stark and deeply entrenched.

READ I Social security net grows, but gaps remain

Rural-urban gender gap

A closer look reveals a telling divergence. Women in rural India participate more in the workforce (41%) than their urban counterparts. This is largely due to their engagement in agriculture and informal home-based labour. In contrast, urban India—home to most formal sector jobs—presents greater barriers to both entry and retention for women. This gap highlights that the problem is not merely one of employability, but of systemic inaccessibility, gendered expectations, and enduring social constraints that erode women’s economic agency.

One of the most pervasive and under-recognised barriers to women’s sustained participation in the economy is the burden of unpaid care work. The 2019 Time Use in India Survey and the Economic Survey 2023–24 confirm that women often exit paid employment not due to lack of skill or opportunity, but because the combined weight of paid and unpaid responsibilities becomes unmanageable. Without affordable childcare, flexible work arrangements, and supportive public infrastructure, ‘the double burden’ continues to push women out of the formal labour force.

Recent policy interventions such as the Maternity Benefit (Amendment) Act, 2017, and schemes like Saksham Anganwadi & Poshan 2.0 (2024–25) have attempted to bridge the gender gap. Yet, even new flexible work norms and informal sector safety nets risk becoming technocratic patches in the absence of a broader cultural reset around gender roles and family responsibilities.

Cultural architecture of inequality

At the heart of the problem lies not just policy failure, but the powerful cultural scripting of gender. In India, patriarchy does more than limit choices—it shapes identity. Marriage, often celebrated as a rite of passage, serves in many communities as an institution of gender discipline. The ideals of the ‘good wife’ and the ‘good mother’ are built on pillars of sacrifice and invisibility. These ideals quietly disincentivise ambition and cast paid work as optional—or even selfish.

This internalisation begins early. Through textbooks, TV soaps, advertising, and even children’s moral tales, girls absorb the message that they are expected to nurture, not lead. Even among the educated urban elite, women are often raised to prize domesticity over professional aspiration. Assertiveness is discouraged; obedience is rewarded. The result is a quiet but powerful cultural ceiling—one that cannot be shattered by employment quotas or skill programmes alone.

By adolescence, girls have already been nudged toward “compatible” careers that accommodate caregiving or part-time work. The ceiling they encounter is not just glass—it is built into the architecture of culture and consciousness.

Gender inequality and struggle for autonomy

Perhaps the most corrosive form of gender inequality is the denial of autonomous decision-making. In countless Indian households, a woman’s choices around education, work, marriage, and motherhood remain subject to the approval—if not the control—of others. Legal adulthood brings few guarantees of personal freedom. This persistent gatekeeping reinforces dependence, dampens agency, and keeps generations of women locked out of the formal economy.

Compounding this disempowerment is the near-total invisibility of women’s biological and emotional wellbeing in public policy. From puberty to menopause, hormonal transitions influence mental health and decision-making capacity. Yet few workplaces—and fewer policies—acknowledge or support these shifts. The result: capable women exit high-pressure careers not from lack of resilience, but from exhaustion without empathy.

Need for cultural re-engineering

India does not merely need more employment schemes for women. It needs a profound shift in how society defines success, labour, responsibility, and womanhood. Gender parity cannot be measured solely through labour force participation or entrepreneurship statistics. True empowerment must address the ecosystem—social, institutional, and psychological—that produces and reproduces inequality.

Education reform must go beyond access to confront the hidden curriculum that perpetuates gender roles. Media must move past glorifying silent sacrifice and begin showcasing diverse, empowered narratives of womanhood. And policy must be rooted in lived experience—factoring in the full emotional and biological spectrum of a woman’s life.

Until these invisible structures are dismantled, India’s demographic dividend will remain half-spent, its growth trajectory lopsided. Empowerment cannot be outsourced to government schemes or CSR tokens. It requires deliberate, cultural reengineering—an overhaul of how we raise our children, design our cities, run our workplaces, and imagine the role of women in public life.

Only when women are truly free to choose—to study, to work, to lead, or to rest—on their own terms, can India claim to be not just rising, but rising equitably.

Shrabani Mukherjee is Associate Professor, Department of Economics, Shiv Nadar University, Chennai.