The fight against gender-based violence in India, halfway through 2025, is marked by unrelenting numbers, structural failures, and the determination of survivors. What is striking is not just the scale but the persistence of the problem, despite louder voices in civil society and more frequent policy interventions. Facts, not platitudes, must now drive accountability.

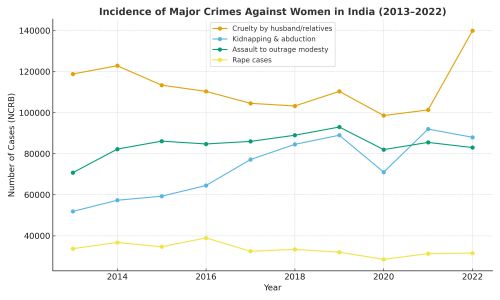

Data from the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) recorded 445,256 cases of crimes against women in 2022, higher than the previous year. These include domestic violence, sexual assault, dowry harassment, abduction, and murder. The largest category was cruelty by husbands or relatives—over 140,000 cases. Rape accounted for 31,516 incidents, while assault with intent to outrage modesty stood at more than 83,000.

Surveys underscore the social normalisation of violence. Nearly one-third of women aged 18–49 report having faced domestic abuse, according to NFHS-5 and independent studies. Improved reporting explains some of the increase, but it also points to the scale of the crisis that remains embedded in everyday life.

READ I Road safety: India’s cities are failing pedestrians and riders

A geography of violence

Some states carry a disproportionate burden. Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, West Bengal, and Madhya Pradesh consistently top the list. Delhi, with high per capita crime rates, shows that urbanisation and prosperity do not translate into safety.

Uttar Pradesh accounts for nearly 15% of reported gender-based violence cases. Yet less than 4% of the Nirbhaya Fund earmarked for women’s safety has been utilised in the state. Political leaders continue to make ritualistic promises while institutions lag in enforcement and accountability.

Layers of discrimination

Gender-based violence in India is inseparable from caste and community hierarchies. Dalit and Adivasi women, as well as religious minorities, face particular vulnerability. The conviction rate for rape of Dalit women is an abysmal 2%, compared to the national average of 25%. Manual scavenging remains predominantly the burden of Dalit women, who make up nearly 98% of those engaged in this degrading work.

Patriarchal attitudes further blur reality. In a 2025 survey, 49% of respondents said men and women face violence equally—an assertion at odds with crime data that shows women are overwhelmingly the victims, usually at the hands of men in domestic or community settings.

Silence, stigma, and new threats

Reporting remains weak, suppressed by stigma, fear of reprisal, and lack of economic independence. Survivors are often pressured into silence by families and communities.

Digital spaces have created new challenges. A regional survey found that three-quarters of women parliamentarians in Asia-Pacific had faced psychological violence online, with 60% receiving direct threats. Meanwhile, child marriage persists at 23%, entrenching cycles of violence and control, particularly in rural areas.

Promise without delivery

India has expanded its legal arsenal against gender-based violence in India. The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (2023) increased punishments for sexual crimes and broadened definitions. One-Stop Centres, Women Helplines (181), Emergency Response Systems, and Fast-Track Courts were introduced to improve access to justice.

Yet outcomes remain weak. Funds are underutilised, fast-track trials drag on, and conviction rates remain flat. The gap between legislative intent and administrative delivery is wide, leaving perpetrators largely unafraid of consequences.

Economic and social costs

Violence against women carries a heavy economic price. Female youth literacy has reached 96% and labour force participation stands at 45%—significant gains. Yet violence forces many to leave jobs, discontinue education, or withdraw from public life. Widowhood or divorce often strips women of autonomy, especially in rural areas, making them dependent on families that may themselves be abusive.

Breaking the cycle requires more than symbolic gestures. Five priorities stand out:

Gender sensitisation in schools and workplaces: Education systems must introduce evidence-based curricula to challenge the normalisation of violence.

Expanded survivor support systems: One-Stop Centres and helplines need more funding, staff, and trauma-informed services.

Justice reform: Fast-Track Courts must function at scale, and police and judicial officers must be held accountable for delays.

Economic empowerment: Policies should support survivors to complete education, acquire skills, and secure jobs, reducing financial dependence.

Digital safety: Law enforcement needs cyber crime capacity to protect women, especially those in public life, from online harassment.

Elected leaders must go beyond rhetoric, allocate resources on time, and enforce laws without bias. Civil society must keep survivor voices at the forefront so that experiences do not get lost in statistics.

India’s gender-based violence crisis is neither new nor without solutions. What it requires is political will, institutional honesty, and a shift from symbolism to measurable outcomes. The country can no longer afford silence or half-measures. Women’s safety, dignity, and freedom demand urgent and fact-driven reform.

Shariq Us Sabah is an independent economist and author.