Recognising the importance of building local capacities, India has pursued targeted industrial policies to develop specific segments of electronics manufacturing and their supporting ecosystems. For decades, however, successive governments struggled to overcome the disincentives created by prolonged free trade in electronics and a hands-off approach to FDI. It was only in the second half of the 2010s, when the domestic market was shielded against imports of selected products, that these efforts began to yield results.

Subsequently, the mobile phone segment that grew significantly under the Phased Manufacturing Program (PMP) had taken over the previously dominant consumer electronics segment by 2016-17. India had also already become a net exporter of mobile phones in 2019-20. However, through the encouragement of local assembly, the PMP had also simultaneously led to a manifold jump in mobile parts and components imports, as several studies had established. This trend has continued under the production-linked incentive or PLI Schemes introduced in the post-Covid years.

READ I Privatisation is no substitute for industrial policy

New vulnerabilities in electronics manufacturing

After the take-off of the PLI Scheme for Large Scale Electronics Manufacturing, the share of mobile phones, which had already accounted for 40% of total electronics industry output in 2019-20, increased to more than 44% by 2023-24 and rose further to account for close to half (48.2%) of the country’s electronics production in 2024-25. Similarly, smart phones have come to dominate India’s electronics exports with its share going up from the already high 26% in 2019-20 to 64.1% in 2024-25. In fact, smart phones have singlehandedly come to dominate India’s manufactured exports and merchandise exports. Such concentration makes the country’s export growth highly vulnerable to demand growth for a single product in its major export markets.

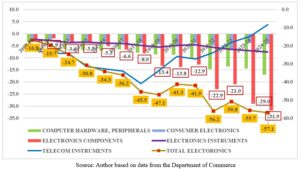

Meanwhile, there has been a significant parallel growth in India’s electronics imports from 2021-22 onwards. With the further shift in the composition of imports—away from the telecom segment towards electronics components, components accounted for as much as 56% of total electronics trade deficit in 2024-25. In 2024-25, imports of telecom parts other than PCBs, with a share of 15% in total electronics imports, ranked a close second to that of the largest electronics imports of semiconductor processors and controllers (16% share).

Against this backdrop, it is commendable that the government has launched the Electronics Component Manufacturing Scheme (ECMS) to give direly needed support for domestic component production. Meanwhile, despite the fact that enormous scale has been achieved in mobile phone production that can support local component production, arguments are being made for reduction in component duties. One of the clear-cut lessons from the history of electronics manufacturing in India has been that duty-free imports disincentivises local production of electronic components (& products) by both domestic and foreign companies.

Zero duty imports also nullify commercial incentives for existing and new indigenous producers to invest in new technologies/R&D and equipment for expanding or upgrading production. It is therefore critical for India to maintain strategic tariff manoeuvring and heightened support for indigenous parts and components makers, along with policies to encourage foreign players to set up their advanced parts and components production locally through joint ventures. It is very pertinent to recall that the government has been extremely strategic in avoiding the country’s entry into RCEP, as none of the post-Covid industrial policies to promote domestic production would have borne fruits if we had joined that mega regional free-trade block.

Meanwhile, given that electronics is the backbone of all digital devices and digital equipment, digitalisation accelerating through the economy is set to lead to a further surge in economy-wide demand for ‘smart’ electronics/digital products. Amidst the opportunities provided by changing geopolitics, and given that leading OEMs and global EMS firms are increasingly moving into more and more technologically sophisticated product segments, electronics manufacturing in India stands to gain from an expansion especially in mature technology products—through subcontracting and otherwise. The expansion of scale in operations will also result in a gradual improvement in the level of domestic value addition. However, amidst the changing technological dynamics in the intelligent era, our policies must be designed to ensure that the output, export and employment benefits of such large public-funded investments become self-sustaining.

Need for a shift in industrial policy

Digital intelligence derived from data is the foundation for innovation and competitiveness in the AI era, and this has led to an increased role for software in all ‘smart’ electronics/digital products. Software is involved not only in the technologies and devices used for data capture, data storage and data transfer; it is software/algorithms that also provide the ability to turn digital data into intelligence. Digital intelligence or AI built on top of data is, in turn, used both for developing new digital products, or/and for improving existing products and processes (Francis 2023).

Under prevailing data governance rules, all first movers (too often lead firms in different global value chains/GVCs or BigTech) that collect data through their software-embedded networked products derive exclusive claims over all possible future uses of the data collected by them. The continuous access to more and more data facilitated through their software-embedded products along with the anti-competitive strategies adopted by these firms allows them to keep refining their data-analytics software/AI algorithms. This, in turn, helps them to design better and more new ‘intelligent’ products, which are patented as software-embedded devices and equipment/machinery, or software systems/solutions, or digital parts and components.

For instance, a recent research study by the author under the Horizon Europe’s TWIN SEEDS project on EU medical device subsidiaries in India found that that software platforms and the software/algorithms embedded in medical devices and equipment are used by medical device firms for continuously gathering and analysing data on the usage and operations of the ‘networked’ device or equipment (i.e. machine-to-machine data), along with that of patients, care providers, healthcare organisations, and, in fact, the entire health sector. Different kinds of collaborations involving domestic stakeholders, along with acquisitions of competitors, Indian tech firms/AI start-ups, etc. enable these firms to gain access to vast amounts of personal and non-personal data (that includes anonymised personal data).

The continuous access to more and more data facilitated through their software-embedded products and anti-competitive strategies allows them to keep refining their data-analytics software/algorithms/AI. This, in turn, helps them to design better and more new ‘intelligent’ products, that is, software-embedded devices/equipment or software systems/ solutions, or active/digital parts and components, all of which are patented. As the GVC literature has proven, the largest portion of value addition in any GVC is captured by the intellectual property rights (IPR) holders.

Without access to similar and expanding sets of data to train algorithms/AI models, other market players will not be able to create more intelligent products that could potentially compete with those of market leaders. This means that even when a growing range of smart electronic/digital products may be increasingly produced domestically, India may witness an increase in net outward forex payments for both goods and services imports in the form of:

(i) proprietary software-embedded devices/components/ equipment; and (ii) proprietary embedded technologies, software solutions/platforms/systems and the like (Francis 2023).

Given the inalienable role of software in developing digital intelligence, India’s ability to leapfrog in the AI era will therefore need a two-pronged industrial policy, in addition to public digital infrastructure provision (Francis 2023).

Across multiple products, components and sub-assemblies that involve software design, fiscal incentives to support local production must be linked to the incorporation of indigenous software designs, to ensure that Indian data does not get trapped in foreign patented embedded solutions/systems and products—which we are imported as proprietary services and goods at a premium into the country. As digitalisation heightens energy and resource-intensive production patterns, additional incentives must be linked to designs that incorporate energy efficiency, carbon neutral processes and environment-friendly materials.

Aggregation of demand through government procurement at the centre, state and local levels, and aggregating demand across digitalising sectors and industries are both critical along this transition. The economies of scale and scope generated by developing these hardware-software synergies across sectors and industries will enable India to fully integrate and benefit from her indigenous software/product design and data analytics capabilities currently leveraged mostly by foreign players. Such a policy approach may also help us to overcome the design control exercised by foreign OEMs on parts and components, which will in turn help build the indigenous digital industrial supply ecosystem.

Simultaneously, we must also put in place a balanced national data governance framework for non-personal data, to create a level playing field for indigenous start-ups and all other indigenous entities to be able to innovate and compete with the first movers, GVC lead firms and BigTech; currently the latter enjoy dominant market positions due to the network effects intrinsic to data-centric innovations.

This centrality of data and digital intelligence in generating and maintaining competitiveness and innovations, and the prime role of software in the same, must be kept in mind before making concessions related to digital clauses in ongoing trade negotiations. The commitments that India makes in trade and investment deals in areas like data flows, ‘open government data’, source codes, etc. can make or break India’s ability to implement a range of necessary digital industrial policies to create and maintain technological leadership and ensure India’s digital sovereignty.

The author is a Bangalore-based economist.