By Ravneet Kaur

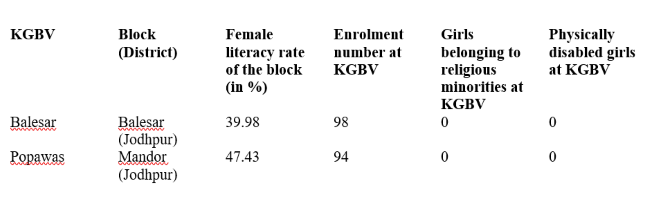

Kasturba Gandhi Balika Vidyalayas (KGBV) are residential schools set up in educationally backward blocks at the upper primary level for girls belonging to the SC, ST, OBC and minority communities in areas where the female rural literacy rate is below national average and the gender gap in literacy is above national average. They are designed to address the issue of high dropout rate among girl students.

Objectives of the scheme is to educate girls from marginalised communities, especially those who are out-of-school or never enrolled. One third of the population in Rajasthan is illiterate and women’s literacy rate is at 52.66%. The dropout rate is 45% among girls against the national average of 60%. The percentage of girls dropping out before completing elementary education among the scheduled castes and scheduled tribes is even worse with only 41%. (NITI Aayog 2015). Disabled children of 5-19 years not attending educational institutions is 31% in Rajasthan, slightly higher than the national average of 27% (Social Statistics Division 2016).

READ I The New Education Policy: Twenty ideas that will shape India’s education system

Issues plaguing KGBVs

Mainstream studies have focussed on the structure of the KGBV scheme, but they miss various crucial social issues such as caste and food choices.

Caste quotient: Caste discrimination in government schools has been elaborated by Ramachandaran and Naorem (2016). They measured types of tasks assigned to different castes and gender in six states. They concluded that tasks like cleaning toilets, playgrounds, classrooms were given to SC/ST and tasks like fetching water for the teacher, washing teacher’s lunchbox and making tea for guests were given to forward castes. A study by All India Dalit Mahila Adhikar Manch (2017) corroborates these facts in their study of KGBVs in Bihar. Similar patterns were observed during our fieldwork in Rajasthan, though there are not explicit, but hidden traces of caste discrimination done by teachers like only Chowdhary/Vishnoi girls are allowed in kitchens, warden room or water filling as they are from upward castes. Such tasks were not carried out by lower castes girls.

Right to choose food: A study by Mukta Agrawal et al. (2018) found out that the schools offered cereal-based diet and other foods including body building food were found deficient. Low intake of milk products, fruits and leafy vegetables reflected in low intake of calcium, vitamin A, iron and other micronutrients, resulting in girld becoming anaemic. Another study by All India Dalit Mahila Adhikar Manch (2017) mentions many girls expressed their desire to have eggs, milk and more vegetables in their diet. Even though the right to food is being met, the right to choose food is not even under consideration.

READ I The digital divide: Why Kerala is not ready for the online education plunge

Cultural influence on the KGBV menu was also observed. Teachers mostly belonged to Brahmin caste or other upward castes so they did not include garlic and onions in the diet. Non-usage of these items were ensured while cooking meals. Also, sources of protein for growing girls were restricted to pulses or cereals only and eggs were not included for the same reason. A majority of the girls are from SC communities that have different dietary habits from Brahmin community.

Child Marriage: It was found that in KGBVs, at least 10% of the girls were victims of child marriage. This was predominantly prevalent in Vishnoi community as they have a tradition of marrying the children during the death ceremony of elders in their house. In Popawas and Balesar, 7 and 4 girls were identified, respectively. It was found that the age of girls was 9- 13 when they were married off. In India, traditions are major contributors to the deplorable violation of children’s right to reach their full potential for development. This highlights that the issue of child marriage.

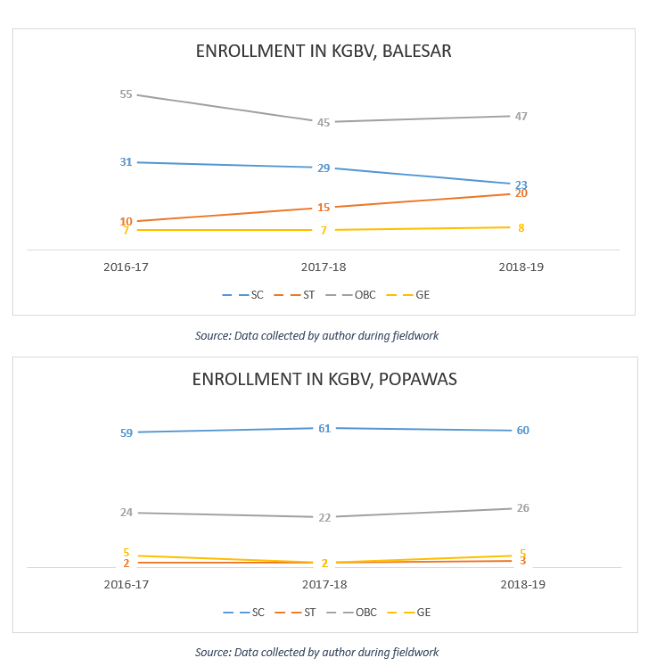

Low enrolment numbers: The admission rate for the KGBVs (given below) reflects lower admission rate for SC/ST compared with OBCs in Balesar, while Popawas has performed better. However, girls from religious minorities were absent and so were girls with special needs.

READ I The five futures that the New Education Policy promises

NITI Aayog in 2015 conducted an evaluation of all KGBVs. It showed that the average number of students enrolled in KGBVs of Rajasthan is 96 whereas, the highest is 248 in Haryana. Both states have almost similar patterns of discrimination against girl child, but contrasting results show the efforts to fight the menace. To understand the issue better, we looked at the existing enrolment numbers at Rajasthan KGBVs during the fieldwork.

The minimum enrolment number of 100 was set at the beginning, which continued to exist as maximum enrolment number due to constraints mentioned below:

READ I Atmanirbhar Bharat: Some practical steps to boost manufacturing in MSME sector

Infrastructure capacity

The first KGBV national evaluation (2009) had identified cleanliness/hygiene as a significant issue in Uttarakhand. It was found that there was improper ventilation, spaces were cramped and the situation was further exacerbated by shortage of toilets and difficulties in accessing water. Another evaluation report observed design inadequacies in the new buildings, for example, kitchen not being provided with storage facilities, platforms, chimney, absence of activity room for girls, libraries in the hostels, teachers’ rooms and labs.

Various studies by Sadhna Saxena highlight the poor sanitation conditions at KGBVs. Similar inadequacies were observed during our fieldwork as well. The space allotted to each KGBV cannot accommodate 100 girls comfortably. It was observed that girls used to share their beds and quilts due to lack of space. Few of the girls had to rotate shifts for sleeping on floor. Many girls were found to be suffering from skin and ear infections and gastrointestinal diseases due to shortage of space and water, unhygienic living conditions, and lack of nutritious too. Already enrolled girls are not finding comfortable space to sleep, in taking more girls will be a management fiasco for the school.

Budgetary allocation

The allocation to education has been dwindling over years. According to NITI Aayog’s 2015 report, in 2011, the budget released for Rajasthan KGBVs was almost Rs 100 lakh less than the outlay. As per the accountability initiative, budgetary allocation to SSA in 2014-15, Rs 54,925 crore was approved, a drop of 22% from 2012-13.

A study by Kumar and Gupta (2008) compared budget allocation to KGBVs and Navodaya Vidyalayas which showed that not only does KGBV receive less money under every head, its teachers are staff get lower salaries and sporadic in-service training inputs. There is no clear demarcation of funds per capita, rather a sum of amount has been given per child, which limits the management of funds. This has become a major impediment in increasing capacity. The 2013 evaluation team found out that students complained of persistent hunger and inadequacy of food. The team also reported that the average utilisation rate for the country against total allocation was only 25% in 2011-12.

Impact of Covid-19

Based on telephonic interviews of headmistresses and wardens of selected KGBVs, we found that the Covid pandemic has amplified the problems of girls from marginalised communities. The digital divide is evident in their villages, leading to poor learning outcomes as each household has single smartphone with limited data capacity. This stops them from attending online classes. Also, many girls belonged to below poverty line families that have lost their livelihoods. Girls might become nutritionally insecure as their households are food insecure and are unable to arrange three meals a day. Right to food ceases to exist in such situations. HMs fear that these girls will become victims of either child marriage or child labour, pushing them deeper into the vicious circle of vulnerability and high dropout rates.

From the prevailing debates on education and the digital divide during COVID, this fragment of educational space remains unnoticed. But KGBVs are crucial for girls belonging to marginalised sections. Along with the focus on increasing capacity, the stakeholders, especially Panchayats, should focus on addressing the daunting challenges affecting the education of girls from marginalised communities. Literacy has been visualised as a crucial tool of development and eradication of illiteracy is central to the war against poverty and unemployment.

(Ravneet Kaur studies for Masters in Public Policy at NLSIU, Bangalore. She can be reached at ravneetk@nls.ac.in.)