Delhi is choking again. The air is toxic, schools are shut, construction has stopped, and emergency plans have been dusted off. The script is familiar, rehearsed, and depressingly cyclical. Each winter, India’s capital gasps for breath. Each spring, the outrage dissipates. Why does a city armed with data, technology, and policy frameworks still stumble year after year? The answer lies not in the weather or in farmers’ fields, but in the failure of governance. Delhi air pollution has become an administrative ritual rather than a public-health priority. What the capital needs is not another seasonal firefight, but institutional reform.

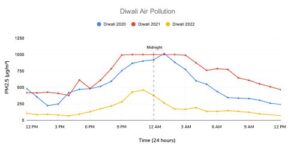

Delhi’s air quality index (AQI) once again crossed the “hazardous” mark this November, touching 500 in several neighbourhoods. SAFAR’s latest readings show PM2.5 levels ten times higher than the World Health Organization’s safety limit. The city’s own emission inventories tell the story. Vehicular pollution contributes roughly 38 per cent of Delhi’s PM2.5 load. Construction dust, road dust, and industrial emissions add another 30 per cent. Waste burning and crop-residue fires from neighbouring states fill in the rest.

READ I How clear cryptocurrency rules can boost digital finance

Why GRAP fails every winter

Scientific conditions make matters worse. Cold air, low wind speed, and a shallow boundary layer trap pollutants close to the ground. For several weeks each year, Delhi becomes a bowl of poison gas. But the meteorology is only the stage. The actors — cars, factories, stubble fires, and administrative inertia — perform the same drama without change.

The Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) was meant to be Delhi’s institutional shield. It defines measures for different levels of air pollution — from banning diesel generators to halting construction. Yet, every winter, GRAP’s activation feels too little, too late. Studies by the Centre for Science and Environment and the Indian Statistical Institute show that GRAP’s “Stage 3 and Stage 4” restrictions often take effect after air quality has already crossed the danger mark.

Forecasting systems like SAFAR and the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology can now predict high-pollution days three to five days in advance with reasonable accuracy. But policy decisions are reactive, not preventive. Bureaucrats wait for the crisis to peak before pulling the levers. The plan that should have been anticipatory has become ceremonial. Even when invoked, its enforcement is patchy: violators of construction or waste-burning bans face small fines, easily absorbed as business costs.

The larger problem is jurisdictional chaos. Delhi, Haryana, Punjab, and Uttar Pradesh share one polluted airshed but act like separate sovereignties. Coordination mechanisms exist on paper; in practice, each state blames the other. When accountability is collective, it quickly becomes invisible.

The economics of Delhi air pollution crisis

Pollution is not just a health issue; it is a macroeconomic one. The World Bank estimates that air pollution costs India nearly 1.4 per cent of its GDP each year through lost productivity, healthcare expenditure, and premature deaths. A study by the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago shows that residents of Delhi could live nine years longer if the city met WHO air-quality standards. That is a measure of both the human and economic loss.

The health burden is staggering: increased hospital admissions for asthma and heart disease, lower worker output, and higher insurance payouts. The productivity cost of poor air quality in Delhi alone runs into billions of dollars annually. Every tonne of particulate matter allowed into the air represents not just environmental neglect but fiscal leakage.

Treating pollution control as expenditure misses the point. Cleaner air yields long-term economic returns — better health, higher productivity, reduced medical costs, and improved investment climate. Beijing’s Clean Air Action Plan, for example, cost about $100 billion between 2013 and 2017, but saved multiples of that through lower mortality and improved worker efficiency.

Delhi air pollution and coordination gaps

Delhi air pollution is regional, but its governance is fragmented. Punjab’s farm fires add smoke; Haryana’s industries add emissions; Uttar Pradesh’s brick kilns add dust. Yet there is no empowered inter-state authority to manage the airshed. The Commission for Air Quality Management (CAQM), established in 2020, was expected to coordinate responses. It remains toothless — issuing directions but lacking fiscal control or enforcement capacity.

Municipal bodies, too, are hamstrung. Their budgets are uncertain, their revenue powers limited, and their mandates overlapping with state agencies. The Delhi Pollution Control Committee, municipal corporations, and transport departments often work at cross-purposes. In the absence of a unified command and clear accountability metrics, enforcement becomes discretionary and episodic.

The private sector, meanwhile, adapts rather than transforms — investing in air purifiers, not in cleaner logistics or production. Public transport expansion is slow, and electric-vehicle adoption, though improving, remains concentrated in higher-income households. The cumulative effect is visible every November — a thick haze of ungoverned externalities.

Towards measurable clean-air outcomes

To escape this cycle, Delhi needs a different approach — one that combines fiscal incentives, technological transparency, and political accountability.

First, budgetary grants to municipalities should be tied to measurable air-quality outcomes. Cities that achieve sustained reduction in PM2.5 levels should receive greater fiscal devolution; those that don’t should face reduced transfers. Performance-linked finance works — it aligns incentives with outcomes.

Second, forecasting must become a trigger for action, not a post-mortem. If meteorological models predict a severe AQI phase, restrictions on construction, industrial activity, and traffic should begin before the spike. That is how Beijing reduced its winter peaks.

Third, empower local governments with predictable funds and clear mandates. Delhi’s municipal bodies should have dedicated clean-air budgets to manage dust, waste, and local emissions. They must also deploy low-cost sensor networks for hyper-local monitoring — making violations visible and immediate.

Fourth, strengthen regional coordination. CAQM should evolve into a true inter-state authority with financial and legal powers. Crop-residue management in Punjab and Haryana requires shared funding and procurement incentives, not just moral appeals.

Fifth, institutionalise year-round action. Pollution does not begin in November, nor end in February. Construction dust, road emissions, and waste burning are perennial sources. The revised GRAP must therefore include quarterly reviews, public scorecards, and independent audits of compliance.

Finally, learn from global precedents. London’s Ultra-Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) and Singapore’s congestion pricing demonstrate that economic instruments — not just prohibitions — can shift behaviour. Delhi’s policy mix still relies too heavily on bans, too little on pricing and accountability.

The governance of clean air

Clean air is a public good, and like all public goods, it requires state capacity. Delhi’s experience shows that technological advances and legal frameworks are futile without administrative will. The capital has the data, the plans, and the committees. What it lacks is a chain of accountability that connects cause to consequence.

Policymakers must therefore embed environmental outcomes into the fiscal system — make air quality part of the performance metrics of cities, departments, and even chief secretaries. Transparency in data, predictability in funding, and certainty in enforcement are the three pillars on which Delhi’s clean-air strategy must rest.

Delhi air pollution is not an accident of geography or climate; it is a man-made failure. Every year the capital rehearses the same ritual — outrage, meetings, bans, and silence. The smog clears, but the system remains clouded. Air pollution is not a seasonal event. It is a continuous governance challenge.

If Delhi wants to breathe again, it must link budgets to results, forecasts to action, and accountability to measurable improvement. The right to clean air is not a privilege of the rich; it is the foundation of public health and economic productivity. The question is not whether Delhi can act. It is whether Delhi’s rulers can learn.