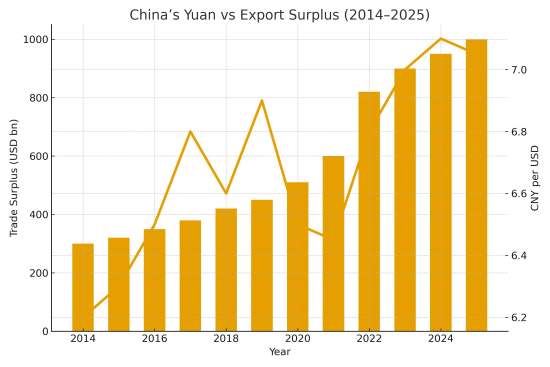

China’s dominance in world trade has entered a new phase. Despite slow domestic growth, a property slump, and weak investor confidence, China’s exports have surged past $1 trillion in surplus this year. The paradox is striking: an economy battling deflation and overcapacity continues to flood global markets with competitive goods. The evidence suggests that weak yuan, maintained through active state intervention, has become a powerful tool of export strategy.

The issue matters now because global supply chains are adjusting to geopolitical tensions, and several countries—including India, the United States, and the European Union—argue that China’s currency management distorts fair competition. A weak yuan lowers Chinese export prices, undercuts competitors, and contributes to large global imbalances. The argument is simple: China’s managed currency regime is enabling an unfair cost advantage in global markets, with significant implications for emerging economies.

READ I Will RBI’s repo rate cuts bring relief to homebuyers?

Weak yuan and export competitiveness

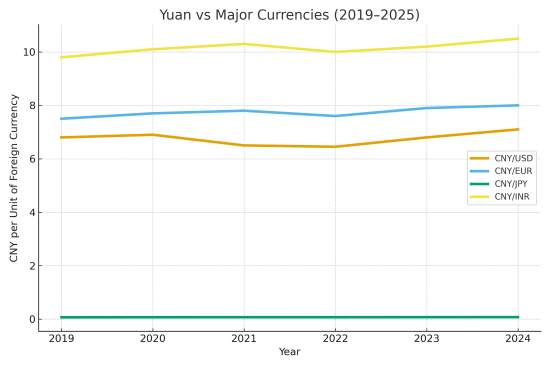

China officially abandoned its hard peg to the dollar in 2005, but the promise of a market-driven currency never materialised. The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) continues to guide the yuan through daily reference rates, state bank interventions, and restrictions on capital flows. Reports show that the yuan trades at around 7.1 per dollar, a valuation many global economists consider weak.

The 2025 currency pattern is revealing. Despite a modest 3–4 percent appreciation against the dollar, the yuan remains undervalued relative to economic fundamentals. IMF estimates cited by former US officials suggest an undervaluation of up to 18 percent. Meanwhile, other Asian currencies—such as the Thai baht, Singapore dollar, and Taiwan dollar—have appreciated far more against the weakening US dollar.

This distortion matters because the weak yuan effectively subsidises Chinese exporters. It lowers the foreign-currency price of Chinese goods, fuels demand abroad, and supports factory utilisation at a time when domestic consumption remains weak. Cheap hotel rooms, consumer electronics, cars, and manufactured goods illustrate a broader trend: China is exporting deflation to the rest of the world.

Overcapacity, deflation, and the currency advantage

China’s weak yuan cannot be separated from the structural weaknesses inside its economy. Chronic overcapacity in sectors such as steel, chemicals, solar panels, electronics, and automobiles has left factories dependent on foreign markets. A depreciated currency helps clear this excess supply abroad and sustain employment in industrial regions.

The weakness of domestic demand is stark. Retail sales remain subdued; industrial production is below trend; and investment, especially in real estate, continues to decline. Chinese households have lost wealth due to the housing market downturn, which has reduced their willingness to spend. These internal pressures push Chinese firms to aggressively cut export prices—supported by the cushion of a weak yuan.

The result is a powerful competitive advantage. A BYD plug-in hybrid car priced at $15,500 in China sells for nearly $50,000 in overseas markets, even after transport and distribution costs. Consumer electronics and solar modules show similar gaps. A weaker yuan allows China to maintain price margins while expanding market share. For many developing countries, including India, such aggressive pricing threatens domestic industries despite protective tariffs.

Global trade imbalances and policy strains

China’s exchange-rate policy has global consequences. With a trade surplus of more than $1 trillion, China is accumulating foreign exchange at a pace unmatched by any major economy. This surplus reflects an imbalance between domestic savings and investment, but it is amplified by currency suppression.

The WTO’s monitoring reports consistently note that China’s currency management remains opaque. Economists warn that persistent undervaluation can trigger retaliatory policies. The United States has long accused China of currency manipulation—though recent trade negotiations have avoided the topic in favour of incremental tariff adjustments.

For emerging economies, the implications are more severe. A weak yuan displaces manufacturing competitiveness in economies like India, Vietnam, Mexico, and Brazil. Their currencies tend to strengthen relative to the yuan, raising export prices. This creates pressure on local producers and complicates industrial policy efforts aimed at diversifying supply chains.

India’s challenge is acute: sectors such as textiles, electronics, solar components, and chemicals face sustained import competition from Chinese producers whose cost structures benefit from the yuan’s undervaluation. The RBI’s real effective exchange rate (REER) data shows the rupee is broadly stable, while the yuan’s REER has weakened to its lowest point since 2012—an indication of a widening competitiveness gap.

Trade, currency, and industrial policy

India’s export strategy cannot be insulated from China’s currency advantage. As Beijing keeps the yuan undervalued to support its export machine, India faces three layers of challenge: preserving manufacturing competitiveness, managing its own exchange-rate stability, and protecting sectors exposed to import surges.

The first line of response is currency management. India maintains a market-determined rupee with limited intervention to smooth volatility. This approach boosts credibility but exposes exporters to pressure when competitors benefit from undervaluation. Coordinated action with other emerging economies through institutions like the IMF, G20, and BRICS may be necessary to highlight systemic distortions caused by China’s practices.

The second response is defensive trade policy. India already uses anti-dumping duties, safeguard measures, and standards-based regulations, but these need to be supported by faster investigations and deeper monitoring of price trends. The surge of low-priced imports across electronics, EVs, solar panels, and chemicals indicates that traditional tariff tools may not be sufficient.

The third pillar is industrial capacity building. India’s production-linked incentive (PLI) schemes, semiconductor mission, and green-energy manufacturing goals require stable demand and protection against predatory pricing. Without policy vigilance, China’s weak currency could undermine India’s long-term industrialisation objectives.

China’s weak yuan has become a critical source of competitive distortion in global trade. A managed currency keeps Chinese exports artificially cheap, supports sectors suffering from overcapacity, and helps sustain a large trade surplus. For countries like India, the impact is visible in stressed manufacturing sectors, widening trade deficits, and persistent import dependence in key value chains.

The policy challenge is not to mirror China’s currency practices but to respond through coordinated economic, trade, and institutional strategies. India’s best options lie in strengthening its industrial base, monitoring currency misalignment through multilateral platforms, and tightening trade-remedy mechanisms. A global trading system cannot function efficiently if one major economy consistently uses its exchange rate as a strategic lever. Addressing the consequences of a weak yuan is therefore central to ensuring fair competition and safeguarding the prospects of emerging manufacturers.