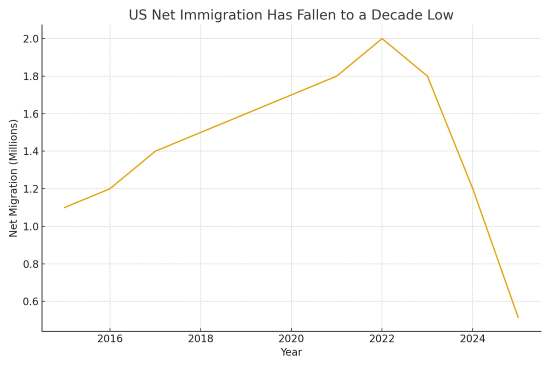

US immigration collapse and labour shortage: The United States has not seen a labour-force squeeze of this scale since the post-war years. The latest estimates from the Federal Reserve show that net migration into the country has fallen from nearly two million a year to about 515,000. The Census Bureau has confirmed the trend, noting slower population growth and widening shortages across critical sectors. Yet the political language in Washington continues to revolve around “closing the border” and “putting Americans first.” Economics, as usual, tells a different story.

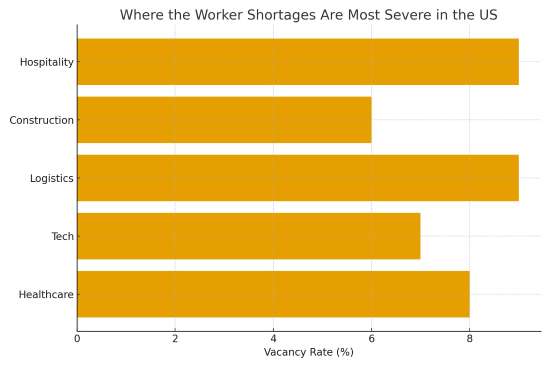

The gap between rhetoric and reality has widened. Hospitals are short of nurses. Tech firms complain about the scarcity of specialised engineers even as they announce headline-grabbing layoffs. Logistics companies report thousands of vacancies. Construction, hospitality, and elder-care services are unable to find workers. The decline in immigration has collided with an ageing population and historically low birth rates. A shrinking labour pool is beginning to weigh on economic growth, wage inflation, and fiscal sustainability.

READ I India-US trade deal nears completion

US immigration decline and shrinking labour force

The Federal Reserve’s most recent research shows how steep the reversal has been. The fall in net migration reflects tighter rules on temporary visas, new processing backlogs, and a shift in administrative policy.

The labour-market effects are visible. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports vacancy rates of 6–9% across healthcare, transportation, hospitality, and construction. In nursing alone, the US faces a shortage of nearly 200,000 professionals.

Tech and AI-related roles are growing faster than the available supply of STEM graduates. Wage inflation has moderated, but not because the labour shortage has eased. Instead, firms are cutting non-essential roles while competing fiercely for specialised talent.

Demographic indicators amplify the challenge. America’s median age is rising. Birth rates are at a four-decade low. The labour-force participation rate for prime-age workers has recovered, but older cohorts are retiring faster than younger workers are entering the workforce. The Congressional Budget Office has already warned that a slower-growing labour force will reduce long-term GDP potential and worsen the debt burden.

No major economy can sustain growth with a workforce that is stagnant or shrinking. The United States is discovering this the hard way.

Policy contradictions behind labour shortage

The contradictions in Washington are striking. The new administration has tightened student-visa scrutiny, accelerated deportations, and imposed new hurdles for H1B, L1, and other work visas. Executive actions have narrowed definitions of specialised knowledge and increased documentation requirements. Asylum processing has slowed. Universities are reporting a drop in international student deposits for the 2024–25 cycle.

Yet industry groups from healthcare associations to technology coalitions are pleading for more workers. Several states have urged Congress to create exemptions for nurses, truck drivers, and AI-related roles. Bipartisan bills proposing higher visa caps remain stuck in committee. Business leaders talk about productivity, innovation, and competitiveness. Politicians talk about border control.

This tension is not new. What is new is the scale of the mismatch between economic need and political posture. A labour-scarce economy cannot function with migration levels last seen in the early 1990s. The irony is that even as political leaders promise to “bring jobs home,” the shortage of workers is pushing firms to move operations elsewhere.

Indian skilled workers face new risks

For India, the consequences are two-sided. India is the largest source of skilled migrants to the United States. More than 70% of H1B visas go to Indian professionals. Indian students form the largest foreign student group, according to the Open Doors report. Nurses from southern India are essential to several state hospital systems.

A decline in US immigration affects each of these channels. H1B processing has slowed. Student-visa approvals have become more unpredictable. Employers are asking for more documentation. The chilling effect is visible in student counselling centres and in the enquiries received by immigration lawyers.

Remittances may also be affected. Indian workers in the US are among the highest contributors to the country’s inward remittances. A slowdown in mobility will eventually reduce these flows.

Yet the picture is not only negative. The sectors most affected by US labour shortages — technology, healthcare delivery, data services, and back-office operations — are also areas where Indian firms excel. Remote work has become a structural feature of the services economy. Global capability centres (GCCs) are expanding their Indian operations. AI-enabled processes allow consulting, health-tech, and financial-services firms to operate with teams partly or fully based in India.

American restrictions are also pushing other advanced economies to adjust. Canada, the UK, and Australia have tightened student and post-study visas in response to domestic politics, opening the door to faster growth in Gulf economies seeking high-skill migrants. Japan and South Korea are opening new sectors to foreign workers. The global competition for Indian nurses, engineers, digital specialists, and AI professionals has intensified.

India’s strategy for global talent mobility

India needs a clearer strategy. Skilled migration has long been treated as a passive outcome of domestic constraints rather than a policy goal. That approach will not work in a world marked by labour shortages, rising protectionism, and renewed competition for talent.

The first step is to upgrade domestic skilling. The demand for cyber-security specialists, AI engineers, advanced-manufacturing technicians, and healthcare professionals is outpacing the capacity of training institutions. A coordinated effort involving industry, universities, and the government is essential.

Second, India must negotiate better mutual-recognition agreements for degrees, certifications, and professional qualifications. Countries facing shortages should find it easier to absorb Indian talent—with safeguards to prevent exploitation.

Third, India needs a stronger system for safe migration. The experience of nurses, gig-economy workers, and semi-skilled migrants shows the gaps in regulation. Restrictive visa regimes increase the risk of abuse. Transparent contracts, standardised migration processes, and better grievance-redress systems are necessary.

Finally, India must double down on remote services. The country already dominates IT and BPO exports. The next wave will come from telemedicine, global design services, AI-assisted consulting, cloud-management operations, and specialised back-office functions for finance and healthcare. If the US cannot import enough workers, it will import more services.

The decline in US immigration is not a passing phase. It is part of a structural shift driven by politics, demography, and economic fear. For India, this is a moment of risk, and opportunity. A coherent strategy for global talent mobility, remote work exports, and safe migration can turn a global labour shortage into a national advantage.

In the decades ahead, the countries that thrive will be those that shape global labour markets. India has the talent, the demographic base, and the technological capability to do so. The question is whether policy will keep pace with the moment.

India must shape the next chapter of global labour markets, not be shaped by them.