Tariff collections have already topped $150 billion this year, the highest on record, and Wall Street has treated each new deal with Europe or Japan as a relief rally. These headline gains flatter the White House narrative that higher US tariffs are cost‑free leverage. Yet the International Monetary Fund’s latest World Economic Outlook warns that today’s 3 per cent global growth projection is tenuous, with tariff uncertainty identified as the chief downside risk. The apparent calm therefore masks a combustible mix — short‑term US windfalls and long‑term systemic damage.

The United States’ effective tariff rate has jumped from about 2.5 per cent to 17.5 per cent in barely seven months. Politically, that delivers a neat talking point: tariffs now raise almost as much for the Treasury as last year’s corporate‑tax cut cost. But economics is not accountancy. Moody’s Analytics calculates that every one‑percentage‑point rise in tariffs pushes consumer inflation up by 10 basis points the following year, eroding any revenue gain. Even Morgan Stanley, hardly a bastion of free‑trade idealism, predicts “slow growth and firm inflation” once dealer stockpiles of tariff‑free inventory run down.

READ I Indian banks must embrace global capital

Inflationary undercurrents at home

Retail prices have not yet spiked because importers front‑loaded shipments before the 15 per cent duties took effect. That cushion “is starting to wear thin,” Morgan Stanley warns. Once it does, the Federal Reserve will confront a policy straitjacket: cut rates to support growth and risk fuelling price rises, or hold rates high and choke investment. Either choice crimps domestic demand just as fiscal deficits widen. In short, the tariff boom is a textbook case of consuming today what must be paid for tomorrow with higher prices, weaker real wages and a crimped policy arsenal.

President Trump’s strategy rests on bilateral coercion: accept 15–20 percent tariffs or risk something worse. Economists see the resulting deals a qualified win for Washington, but are sceptical that the promised foreign investment will ever materialise. More worrying is the precedent. Multilateral rules built over seven decades are being replaced by a patchwork of power‑based bargains, eroding the most‑favoured‑nation principle and sidelining the World Trade Organisation.

When tariff exemptions depend on presidential favour, investment planners everywhere demand higher risk premia, diverting capital from productivity‑enhancing projects to precautionary stockpiles and legal fees. That invisible tax will not show up in next quarter’s GDP release, but it will drag on growth for years.

US tariffs and emerging economies

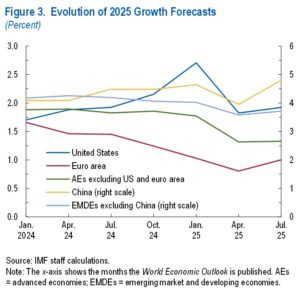

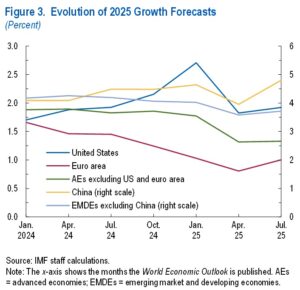

The IMF notes that apparent resilience is “underpinned by fleeting forces” such as advance buying ahead of tariff deadlines. Once those purchases fade, supply‑chain disruption will hit export‑oriented economies first. A stronger dollar—up nine per cent this year as investors seek US assets—magnifies the shock by inflating dollar‑denominated debt servicing costs.

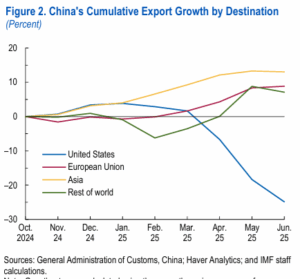

In Asia, where trade with the United States drives factory orders, higher duties already coincide with tighter credit conditions and falling capital expenditure. The tariff war is thus exporting stagflation risks to economies least equipped with fiscal space, jeopardising the demand that sustains US tech and farm exports.

Think tanks warn of a “slow‑burn efficiency loss” as firms re‑engineer supply chains to navigate country‑specific tariffs. Designing a product so that inputs from Vietnam attract a different duty than those from Mexico is no one’s idea of value creation. The administrative burden diverts managerial attention and capital from research, automation and worker training. Worse, rules‑of‑origin mazes encourage round‑tripping and invoice gaming, breeding the very uncertainty business hates. The ultimate cost is a smaller productivity frontier—exactly the opposite of what American workers were promised.

Restore rules, not raise walls

The lesson from a century of trade policy is clear: temporary protection often ossifies into permanent distortion. To avoid that fate:

Codify deals multilaterally. Congress should insist that any tariff agreement be lodged with the WTO and include measurable sunset clauses.

Target adjustment assistance, not blunt tariffs. If the objective is supply‑chain security, use transparent subsidies for critical sectors and skills training rather than universal import taxes.

Re‑engage allies on reform. The EU and Japan have capitulated out of fear; they would support a collective initiative to update global trade rules on subsidies, carbon border adjustments and digital commerce.

Strengthen the Fed–Treasury coordination channel. A credible plan to cap the effective tariff rate would give the Federal Reserve room to manage inflation without sacrificing growth.

History will remember whether Washington chose to lead a reform of the trading system or dismantle it. Short‑term tariff trophies may thrill markets today, but the bill—higher prices, fractured alliances and diminished global growth—will arrive soon enough. The prudent course is to change direction before that invoice falls due.