State capital expenditure remains one of India’s strongest levers for long-term growth. It builds the public assets that raise productivity and draw in private investment. Yet most states continue to fall short of the capital outlays they announce. The gap between budgeted intentions and actual spending reflects deeper structural weaknesses in sub-national public finance.

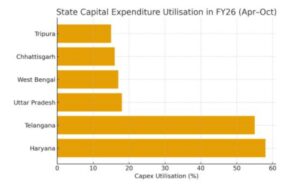

The latest monthly accounts from the Comptroller and Auditor General show that in the first seven months of FY26, states spent only 33.5% of their annual capex allocations. Haryana and Telangana were early spenders, but large states such as Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Chhattisgarh and Tripura used less than one-fifth of their targets. This pattern has persisted despite higher central support and a stable macroeconomic environment.

READ | Bihar economy: The state must fix fiscal and logistics gaps

Revenue uncertainty undermines capital spending

States prepare ambitious Budget Estimates based on optimistic assumptions of revenue. The end of GST compensation in 2022 removed an important buffer. State excise revenues are volatile. Transfers from the Centre, including Finance Commission grants and centrally sponsored schemes, are often delayed or tied to specific conditionalities.

When revenues fall short, states protect salaries, pensions, subsidies and interest payments. Capital outlays are postponed because they offer the most flexibility. The RBI’s State Finances Report shows that committed expenditure now absorbs over half the revenue receipts of several states.

Centre’s fiscal choices shape state capex

The Centre’s fiscal stance has also altered the capex by states. Union Budgets now undertake more than 60% of general government capital expenditure, shifting the balance between central and state investments.

Cuts in centrally sponsored schemes and shrinking untied transfers limit state autonomy. Scheme-linked funding also introduces uncertainty because disbursements vary across the year.

The Centre’s 50-year interest-free capex loans are well intentioned but contingent on reform milestones that many states find difficult to meet. This central dominance has boosted national capex numbers, but it has also reduced the space for states to design and execute their own investment priorities.

Salaries and pensions have grown rapidly due to Pay Commission awards and expanded payrolls. Interest costs have risen as states borrowed heavily during and after the pandemic.

This rigid structure leaves little discretionary space. When revenues weaken, states adjust by reducing capital formation. This structural rigidity ensures that capex becomes the shock absorber during fiscal stress.

Delayed payments and arrears distort cash flows

A growing share of state liabilities arises from unpaid bills. Contractor payments, subsidy arrears and power sector dues create cash-flow pressures that squeeze capital budgets.

The PRAAPTI Portal shows power sector dues crossing ₹1.3 lakh crore in 2024. Governments facing large arrears delay contractor payments or slow project execution. This dampens private sector interest in infrastructure development and raises project costs due to claims and penalties.

Arrears shift resources away from asset creation and reduce the credibility of state procurement systems.

Political incentives favour populism over assets

The political economy remains a central constraint. Welfare schemes deliver quick electoral dividends. Capital projects take longer and often extend beyond a government’s term.

This creates a bias toward subsidies and cash transfers and away from long-gestation public infrastructure. The incentive structure favours visibility and immediacy rather than durable productivity gains. IMF research shows that countries with sustained political commitment to public investment achieve better capex outcomes even at comparable levels of fiscal capacity.

Weak administrative capacity slows execution

Project preparation remains uneven. Detailed project reports, environmental clearances, tender processes and land acquisition require specialised skills. Many departments remain understaffed or reliant on external consultants.

As a result, states struggle with execution in the early part of the year and rush spending in the final quarter. This “March rush” is a recurring finding in CAG reports, reflecting administrative bottlenecks rather than weak intent.

Quality of capex needs greater scrutiny

Quantity alone is not a measure of effectiveness. Many states spend disproportionately on administrative buildings, boundary walls or small works that offer limited productivity gains. CAG audits repeatedly flag cost overruns, poor project design, and the absence of asset registers.

Without stronger scrutiny of project selection and evaluation, even higher spending may not generate the desired economic outcomes.

Centre–state dynamics and the coming shift

Inter-state disparities in fiscal health are widening. Revenue-rich states have diversified tax bases and stronger administrative systems. States in the Hindi heartland and the Northeast depend heavily on centrally transferred resources and therefore set ambitious capex targets without the capacity to deliver them.

This structural challenge will gain significance when the 16th Finance Commission announces its recommendations. The devolution formula, grant allocations and design of special-purpose transfers will shape state capex capacity from FY27 onward. Changes in horizontal devolution will alter the fiscal space of poorer states and influence their ability to undertake long-term investments.

Reform agenda for stronger state capex

Strengthening state capex needs structural reforms. Medium-term fiscal frameworks must ring-fence capital outlays from revenue volatility. Borrowing limits can be linked to capex efficiency instead of uniform deficit caps.

States must invest in project preparation systems and transparent procurement processes. Timely clearance of arrears and tighter oversight of contingent liabilities will improve investor confidence. Digital monitoring and cross-department coordination can further reduce execution delays.

The argument centres on treating capital expenditure not as discretionary spending but as a foundational requirement for growth. India’s next decade will depend as much on state fiscal discipline and administrative capacity as on the Centre’s investment push.

A stronger state-level capex framework is essential for sustaining the country’s investment cycle.