Several state governments have joined the chorus for the reinstatement of the old pension scheme. The demand for dumping the new pension scheme that came into force in 2004 got louder with Punjab joining the bandwagon. Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan, and Jharkhand had already announced that they will restore statutory pension scheme for state employees, while Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Andhra Pradesh are expected to follow suit.

The matter is generating a heated debate with opposition parties promising to bring back the old pension scheme if voted to power in the upcoming assembly elections in Gujarat and Himachal Pradesh. However, the Pension fund Regulatory and Development Authority has made it clear that the law doesn’t allow the transfer of funds collected under the NPS, throwing a spanner into the efforts to replace NPS with old pension scheme.

READ | Vikram S success marks private sector success in space industry

Old Pension Scheme vs New

Under the older regime, pension to the employees of both the Union and state governments was fixed at 50% of the last drawn basic pay. Also, just like the salaries of employees, monthly pay-outs to pensioners also increased with hikes in dearness allowance. DA is an adjustment offered to employees and pensioners to make up for the increase in cost of living and is announced twice a year. According to the current government pay scales, the minimum pension is Rs 9,000 a month and maximum is Rs 1,25,000.

The government had switched to the new pension scheme as the former regime only ballooned government liabilities as no accretions towards a pension fund were made to fulfil this obligation. The current generation of taxpayers paid for the current pensioners. The OPS was found to be unviable as pension liabilities kept climbing every year. Better healthcare meant life expectancy improved which meant longer pension pay-outs. Hence came the new pension scheme.

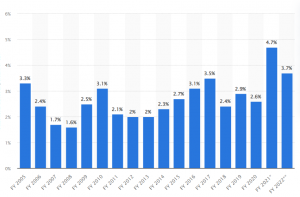

Fiscal deficit of states as % of GDP

With the New Pension Scheme notified in December 2003, the defined contribution comprised 10% of the basic salary and DA by the employee and a matching contribution by the government. The same was increased to 14% later. The NPS allows subscribers (government employees) to decide where they want to invest their money by contributing regularly into a pension account throughout their career. After retirement, they can withdraw part of the pension amount in lump sum and use the rest to buy an annuity for a regular income.

The opposition against the new regime is on simple grounds — that retired service personnel and government employees prefer the visibility of a defined or assured-benefit scheme such as the OPS over the relative opacity of the defined-contribution NPS.

While some states are opposing the 2004 scheme and opposition parties making promises to bring back the old system, they are ignoring the fundamental reason why these states switched to the new system at the first place. The old system is plainly unviable for state finances, especially at a time when the fiscal deficit of several states is at alarming levels.

In fact, it was for this very reason that all states other than West Bengal had voted for NPS and made it compulsory for employees joining after April 1, 2004. Further, in the 2000s, India’s pension debt was reaching uncontrollable levels which led to the government making a committee to adapt a better pension system. The NPS significantly reduces burden from the shoulders of the state government while under OPS, the government bore the entirety of the burden.

READ | India-Australia FTA will boost trade in services, minerals

Currently, the state finances are in distress. The indebtedness of states is expected to remain elevated at 30-31% this financial year. This is slightly lower than the level of 31.5% seen in fiscal 2021-22. The state governments need to borrow from the Union government when they are unable to meet various fiscal obligations such as subsidies.

Pension pay-out as a share of states’ own tax revenue make an alarming reading. For some states the figure is as high as 79.93%. Himachal Pradesh, for instance, has a revenue of nearly Rs 9,100 crore while its pension outgo is around Rs 7,266 crore.

The state governments’ plan to bring back the old statutory pension that has been proved unviable reeks of populist compulsions of electoral politics. If state governments take on the additional responsibility, they will be left with little to invest in productive assets and income support to the poorest. The state governments must understand the fiscal picture and withdraw from the attempt to reinstate statutory pension.