India-US trade talks: On 28 May the US Court of International Trade struck at the heart of President Donald Trump’s trade arsenal, ruling that the International Emergency Economic Powers Act does not let a president levy blanket import duties. In unusually sharp language the judges said that if the tariff orders were unlawful for the small businesses that sued, “they are unlawful for everyone.”

Within twenty-four hours the Federal Circuit Court granted a temporary stay, reinstating the tariffs while it hears an appeal. Yet the episode has laid bare the fragility of Washington’s coercive trade tools and—inadvertently—handed India a sliver of negotiating space before US envoys land in New Delhi on 5–6 June for what both sides hope will be the final round of bilateral trade talks.

READ I Trump’s tax cuts risk ballooning US debt crisis

Leverage — real and imagined

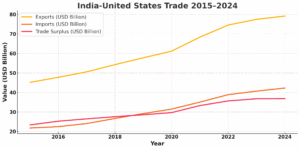

For years the Trump team cited India’s goods trade surplus to demand swift concessions, ignoring the services surplus that flows the other way and the handsome profits US corporations repatriate from their Indian operations. The imbalance is rhetorical, not existential. Yet it has allowed Washington to press for duty cuts on bourbon and big bikes, market access for genetically-modified corn and soy, and drug-patent rules friendlier to Big Pharma.

India has already sweetened its offer—remember the Budget-day duty trims on whiskey and motorcycles—and agreed a wide-ranging terms of reference only hours before a threatened 26% “reciprocal” tariff was to kick in on 8 April.

The message from Washington was blunt—sign quickly or pay dearly.

India-US trade talks and the ruling

Does the court’s rebuke neutralise that threat? Not quite. As analysts are quick to note, Mr Trump retains older but serviceable weapons—Section 301 for unfair practices, Section 232 for national security, and Section 122 of the 1974 Act that lets him slap emergency duties of up to 15% for 150 days without lengthy investigations.

In other words, the legal foundations have cracked, but the edifice still casts a long shadow. American negotiators will arrive for the India-US trade talks with fewer cards, but not empty-handed. Indeed, the speed with which the administration secured an appellate stay signals it will fight all the way to the Supreme Court—and may escalate other tariff lines in the meantime. India-US trade negotiations offer an opportunity, not a victory lap.

What India wants—and what it must avoid

Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal says the India-US trade agreement is “well on track” and politely insists that US court battles are an internal affair. The instinct is sound; nothing irritates Washington more than foreign commentary on its litigation. But behind closed doors New Delhi must hard-code three red lines.

First, agriculture. Opening the gate to GM crops would ignite domestic backlash and fracture the small farmer coalition that underpins rural stability. India has managed to ring-fence agriculture in every trade pact since ASEAN; giving way now would create a precedent every future partner will cite.

Second, intellectual-property evergreening. US negotiators want Section 3(d) of India’s Patent Act watered down. That clause, which curbs trivial drug-patent extensions, is the spine of our generic-medicine success. Diluting it would raise healthcare costs not only at home but across the global South that depends on Indian generics.

Third, data localisation. Multinationals crave free data flows; Indian regulators see localisation as a lever for competition, taxation and security. A premature pledge could lock India out of the very digital-public-infrastructure model it now promotes via UPI and ONDC.

A negotiator’s checklist

New Delhi’s negotiators at the India-US trade talks need to play three boards at once—the law, the calendar and the economy.

The decision of the United States Court of International Trade may ultimately be upheld; if so, congressional action would be needed for any across-the-board tariff. That would lengthen US timelines and dilute presidential leverage. India need not concede today what can be deferred until tomorrow’s legislation.

US mid-term elections loom in November 2026. An interim deal that “saves American jobs” is campaign gold for Mr Trump. That gives India bargaining power: Washington needs a headline sooner than New Delhi does.

With supply chains scrambling for “friend-shoring” destinations, India’s $500-billion manufacturing base looks more attractive than ever, and services exports are at an all-time high. A bad trade deal—not a delayed one—is the real risk.

A shrewd strategy therefore is to conclude a narrow “early harvest” package that locks in tariff relief on labour-intensive exports—textiles, gems, marine products—while parking thornier issues (digital trade, agriculture, pharmaceuticals) for a phase two that begins only after the US legal dust settles.

Engage, hedge, reform

Engagement does not preclude hedging. India should simultaneously accelerate talks with the EU and revive dialogue with ASEAN on upgrading the 2010 FTA. Diversification dilutes any one partner’s leverage. At the WTO, New Delhi ought to join like-minded members to clarify that IEEPA-style measures are incompatible with multilateral rules—a legal backstop if Section 301 is redeployed.

Domestic reform is the final, often forgotten, pillar. India’s cumbersome customs clearance, unpredictable tariff tweaks and ad-hoc quality controls erode the value of any preferential access it may win abroad. Streamlining ports, digitising compliance and providing regulatory certainty would raise export competitiveness far more durably than a hurried bilateral deal.

Use the breathing space wisely

The CIT ruling has punctured the aura of inevitability that surrounded Mr Trump’s tariff threats; the appellate stay reminds us that the sword still hangs. In this brief interregnum India should do what seasoned litigators do: ask for more time, narrow the scope, and insist on language that ties tariff relief to objective benchmarks, not presidential discretion.

If New Delhi signs away core interests merely to avert a tariff that may never survive judicial scrutiny, it will have squandered a strategic opportunity. But if it leverages the moment to secure balanced market access while defending agriculture, affordable medicines and data autonomy, the much-anticipated bilateral trade agreement could yet become a template for equitable commerce in an era of economic nationalism.

Great negotiations, like great litigation, are tests of patience. The court has given India a breather; the question is whether we can breathe and bargain at the same time.