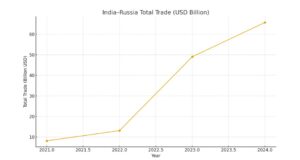

India-Russia trade ambitions: The annual India-Russia summit ended with confident declarations. New Delhi and Moscow agreed to widen cooperation across energy, technology and manufacturing. President Vladimir Putin’s first trip to India since the start of the Ukraine conflict added political weight to the agenda. Both sides projected bilateral trade—currently $65–70 billion—would rise to $100 billion by the decade’s close.

But this optimism faces a difficult global backdrop. Western sanctions on Moscow are tightening, and the United States has warned of secondary sanctions on companies, logistics operators and financial intermediaries linked to Russia. These pressures carry direct consequences for Indian refiners, exporters and banks. India must balance its longstanding strategic ties with Russia against the need to stabilise exports, defend the rupee and secure a broader trade understanding with the US.

READ | Rupee depreciation: The currency faces a slow, structural slide

Structural imbalances in India-Russia trade

The joint statement listed an impressive set of goals: reviving a rupee–rouble settlement mechanism, expediting discussions on an FTA with the Eurasian Economic Union, and expanding cooperation across crude oil, fertilisers, coal, nuclear energy, space, tourism and labour mobility.

However, each ambition runs into a basic structural constraint—India imports far more from Russia than it exports. Indian exports stand at $4–4.5 billion, dominated by pharmaceuticals, textiles, machinery, tea and coffee. Imports, driven largely by crude oil, exceed $60 billion. The imbalance has left Russian banks with large, unusable rupee surpluses that cannot be redeployed. Unless trade becomes more balanced, even the most sophisticated currency settlement system will struggle to function.

Limits of de-dollarisation workarounds

Efforts to design alternative payment channels have yielded limited results. India and Russia have experimented with settlement through third-country currencies such as the UAE dirham, and have explored linking India’s real-time payment architecture with Russia’s SPFS, a domestic alternative to SWIFT. These solutions offer partial relief but remain exposed to sanctions.

Secondary sanctions can target intermediary banks and shipping insurers, not just direct Russia-linked entities. The broader push to dedollarise trade flows will continue, but its durability depends on the willingness of global institutions to carry compliance risks. For now, the payment system remains vulnerable.

Oil dominates, but its advantage is shrinking

Crude oil still accounts for over 80% of India’s imports from Russia. Since 2022, discounted Russian crude has boosted margins for Indian refiners and supported exports of refined products. But the advantage is narrowing. Discounts have shrunk, compliance risks have grown and shipping disruptions have become more frequent. Even a marginal tightening of sanctions on tankers, insurers or payment channels could undermine this trade.

Such dependence on a single commodity makes the headline trade figure misleading. Without stable, diversified flows, bilateral trade growth will remain exposed to geopolitical swings.

India’s energy relationship with Russia spans more than crude. Russia has become a significant supplier of thermal coal for power and steel production, and long-term contracts for nuclear fuel support existing and planned reactors at the Kudankulam Nuclear Power Plant. Prospects for LNG remain constrained by geography, but Moscow has expressed interest in downstream petrochemicals partnerships. These links hold strategic value but face the same constraints: sanctions, freight risks and Russia’s wartime industrial pressures.

Export optimism runs ahead of reality

The summit projected a dramatic increase in India’s exports to $30–35 billion by 2030. This aspiration faces obstacles in cargo security, payment reliability, and banking access, especially with Russia cut off from SWIFT.

More fundamentally, Russia’s wartime economy has distorted demand patterns. Import needs today are shaped by short-term military requirements rather than structural economic shifts. This makes demand volatile, unpredictable and unsuitable as a foundation for stable export growth. Unlike China, Russia lacks the industrial breadth needed to supply India with high-value electronics, machinery or intermediates.

Any sustained rise in trade flows depends on logistics. This brings the International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC) into focus. The route—running through Iran and the Caspian Sea—offers potential reductions in transit time and cost. But its viability is hostage to geopolitical stability. Sanctions on Iran, capacity constraints in the Caspian region and insurance restrictions on high-risk transit corridors complicate usage. India’s investment in Chabahar port strengthens access to Central Asia, yet it cannot fully shield operators from sanctions-driven uncertainties.

FTA with Eurasian Economic Union

Progress on a free trade agreement with the Eurasian Economic Union has been slow since negotiations began in 2017. Tariff reductions may help at the margins, but they do not fix the underlying issues—payment bottlenecks, logistics risks and shifting geopolitical alignments. Member states have recalibrated priorities as the Ukraine conflict reshapes the region, leaving limited space for fast-tracked negotiations.

India’s engagement with Russia is inseparable from its broader multi-alignment strategy. Moscow’s deepening strategic partnership with Beijing narrows India’s room for manoeuvre. Yet Russia remains vital in defence procurement, nuclear energy, and multilateral coordination through BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. Balancing these interests against India’s far larger economic relationship with the United States is becoming more complex. Engagement with Russia may provide diplomatic leverage, but it cannot replace the scale, investment and technology links that India draws from Western economies.

A grounded view of the road ahead

Even if external risks are moderated, India must address internal constraints to make its export ambitions credible. Exporters face recurring bottlenecks in port capacity, customs efficiency, export credit availability and specialised logistics for pharmaceuticals, engineering goods and perishables. The Economic Survey has stressed the need to modernise freight corridors, improve standards harmonisation and deepen export finance markets. Without these reforms, India will struggle to deliver the multi-fold increase in exports that policymakers foresee in the Russian market.

Putin’s visit signals that Moscow retains influential partners in Asia and that India will continue to pursue an independent foreign policy. But trade projections must rest on economic logic rather than diplomatic sentiment. The architecture of bilateral commerce is shaped by sanctions, logistics constraints and structural imbalances—not summit communiqués.

India and Russia will continue to engage deeply, especially in energy, defence and nuclear cooperation. But the trajectory of their economic partnership will be defined by the realities of geopolitics and global finance, not by ambitious targets. The prudent path is calibrated engagement backed by domestic reforms and diversification. Only then can India secure growth in a market that remains both strategically valuable and economically constrained.