India-EU FTA: After nearly two decades of negotiations, India and the European Union have closed a free trade agreement that is large in scale, cautious in design, and unmistakably strategic in intent. The deal arrives not as a triumph of free-trade idealism but as a response to disruption caused by US tariff volatility, supply-chain re-shoring, and the erosion of predictability in global trade.

The announcement by Narendra Modi and Ursula von der Leyen is best read less as a commercial breakthrough than as an act of economic statecraft. For both sides, the agreement is a hedge against an unreliable United States and a recalibration toward partners that still value rules, scale, and institutions.

READ | GSP withdrawal by EU tightens the squeeze on Indian exporters

Why India-EU FTA now

Trade negotiations between India and the European Union were relaunched in 2022 after a nine-year hiatus. What changed was not the technical feasibility of the deal, but the strategic environment. Washington’s turn toward unilateral tariffs, culminating in a 50% duty on Indian goods and the collapse of a bilateral India-US trade pact, altered incentives on both sides.

For Europe, the India deal follows agreements with Mercosur, Indonesia, Mexico, and Switzerland. For New Delhi, India-EU FTA complements recent agreements with the UK, New Zealand, and Oman. The pattern is unmistakable. Middle powers are building trade buffers to insulate themselves from a US that has become transactional, erratic, and politically inward.

The economic weight of the agreement

India–EU trade already stands at $136.5 billion annually, making the EU India’s largest trading partner. Together, they account for roughly a quarter of global GDP and nearly two billion people. This agreement is the largest trade pact ever concluded by either side.

READ | India-EU FTA and the emerging global economic power

European estimates point to a doubling of EU goods exports to India by the early 2030s, annual duty savings of around €4 billion, and tariff elimination or reduction on roughly 90% of tariff lines. India gains preferential access to a high-income market that remains open to services trade, skilled labour mobility, and standards-driven manufacturing.

The scale matters. But so does the structure.

Tariffs: asymmetric liberalisation by design

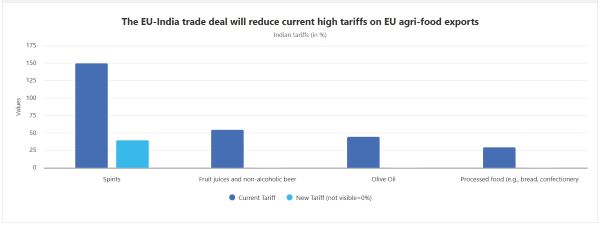

India enters this agreement with some of the world’s highest applied tariffs, particularly in automobiles, alcohol, and agri-food. Duties on imported cars, for instance, can exceed 100%. The deal does not dismantle this wall overnight. Instead, it introduces quotas, phased reductions, and safeguards that protect domestic manufacturers while allowing controlled market entry for European firms.

This asymmetry is intentional. India has learned from earlier FTAs where rapid tariff liberalisation outpaced domestic adjustment. The EU, for its part, retains full protection for politically sensitive farm sectors such as beef, dairy powders, sugar, rice, poultry, ethanol, while allowing limited access under strict safeguards.

The result is not free trade in the classical sense. It is managed openness, calibrated to domestic political economy on both sides.

Services and labour mobility

The most consequential gains for India lie outside tariffs. The agreement expands access for Indian IT services, digital firms, engineers, and professionals into European markets where demographic ageing and skill shortages are structural.

While the deal stops short of unfettered labour mobility, it improves recognition of qualifications, short-term entry for professionals, and market access in areas such as financial services, maritime transport, and digital trade. For an economy where services account for over half of GDP and a rising share of exports, this is a material advantage.

It also explains Europe’s interest. India offers not only a consumer base of 1.4 billion people but a deep pool of human capital at a time when productivity growth in Europe is under strain.

Global value chains, not import substitution

The agreement signals a subtle but important shift in India’s trade strategy. Rather than treating FTAs as export-promotion tools alone, New Delhi is using them to reposition itself within global value chains.

Lower tariffs on European machinery, components, and capital goods reduce the cost of producing in India for export. This is particularly relevant for electronics, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, and automotive components. The EU–Vietnam FTA offers a precedent: when tariff cuts are paired with investment and standards alignment, export upgrading can be rapid.

This outcome is not automatic. Indian firms will face stringent European requirements on quality, traceability, environmental compliance, and labour standards. The agreement opens the door; it does not carry firms through it.

Sustainability and standards

The EU has insisted on strong commitments on labour rights, climate obligations, and sustainability. India has accepted these, including alignment with the Paris Agreement and cooperation on environmental standards.

The risk of regulatory overreach is real. Compliance costs can be high, especially for small exporters. But the alternative, remaining outside high-standards markets, is costlier in the long run. As carbon border measures, due-diligence laws, and ESG norms spread, access to Europe will increasingly depend on regulatory convergence.

In that sense, the deal accelerates a reckoning India cannot indefinitely postpone.

Consumers gain, but slowly

Indian consumers will see tangible effects over time. Tariffs on European wines, spirits, olive oil, processed foods, and medical equipment will fall gradually. Premium automobiles will enter under quota-based lower duties. The impact will be visible but not transformative. Luxury will become more attainable, not mass-market.

More important are indirect effects: cheaper inputs for hospitals, manufacturers, and exporters; greater competition in high-quality segments; and pressure on domestic firms to upgrade.

Price outcomes will still depend on GST, state taxes, logistics costs, and firm strategy. The deal shapes direction, not final outcomes.

READ | India-EU FTA: Strategic deal, limited ambition, real gains

What the deal does not do

It does not replace the US market. India’s trade surplus with the US is nearly twice that with the EU. Nor does it resolve all irritants such as investment protection, geographical indications, and dispute settlement will be handled in parallel agreements.

Nor is implementation immediate. Legal vetting will take months, ratification longer, with full operation expected around 2027. Political durability will be tested not at the signing ceremony but in parliaments, courts, and customs offices.

Domestic execution is the real test

The agreement’s success will hinge less on Brussels than on New Delhi. Can India align skills, apprenticeships, testing infrastructure, and regulatory capacity with European benchmarks? Can state governments, customs authorities, and regulators deliver predictability? Can small firms be helped to navigate compliance rather than priced out of it?

Trade deals do not generate growth by themselves. They reward preparedness and punish complacency.

The India–EU trade agreement is not a celebration of globalisation’s past. It is an adaptation to its present. Both sides are hedging against a fractured world, using scale and rules where force and tariffs have become fashionable elsewhere.

That makes this deal less romantic than the rhetoric suggests—and more important than it appears at first glance.