Ethical questions over alcohol revenues: It may take some effort to jog one’s memory and recall the incident that enraged the nation at Bisada village in Uttar Pradesh. Bisada assumed notoriety after 55-year-year-old Mohammad Akhlaq was lynched by a mob in September 2015 over suspicion of cow slaughter. While various narratives emerged over the incident, what didn’t gain much traction was an issue raised by the family of the victim – alcoholic ways of local youth.

Rising inebriation is a common concern raised time and again by various voices across the country. Liquor is more accessible with several state governments permitting/ proposing its home delivery, including by e-commerce. Opening of liquor vends after the phase I of the Covid-19 pandemic in New Delhi and many other key cities saw serpentine queues since the lockdown had resulted in forced abstinence for alcohol consumers. Adding complexity to this is the trend of Indian states becoming active participants in liquor trade, eyeing the revenue potential of the business.

READ I TechFins: Why India must stop their unregulated, untaxed run

Liquor taxes in state finances

The principal means employed by the states to raise resources is taxation. Setting up of an efficient and fair tax regime is a complex endeavor involving both polity and policy imperatives. Taxation gives leverage and also prominence to a consistent revenue stream which, in turn, can ensure some sort of an assured appropriation for the funding of the government’s requirements. As economic development progresses, additional needs arise for tax revenues that could finance further public spending.

In the context of Indian states, this additional demand can be met from a handful of sources — income tax, corporate tax and various cesses go to the Union government. States can only earn revenues from out of its share of GST, excise, sales tax, and taxes from registrations. What begs consideration here is the quality of resources so raised through taxation.

- Can taxes and levies have an ethical basis? And even if they can, should they? And how does one define the contours of such ethics?

- How does the State define what’s morally correct?

- Should the color of money be important?

- Can a government entity go in for taxation of a sort that does not target revenue collections alone, but is levied instead from the measurable social impact it can potentially have?

- Both effectiveness (whether the tax enhances or diminishes the overall welfare of those who are taxed) and equity (whether the tax is fair to everybody) matter.

The Finance Commissions, constituted to determine the financial arrangements between the Centre and the States for a five-year period, encourage states to generate their own revenues to fund their activities. To quote from the Fifteenth Finance Commission, “Own non-tax revenues of the states include interest receipts, dividends and profits, royalties, irrigation receipts, receipts from forestry and wildlife, receipts from elections, etc. These revenues grew at a trend rate of 9.9% during 2011-12 to 2017-18.”

Some of the previous Finance Commissions were fulsome in praise for states on this account, noting an overall improvement in state finances, which was felt to be driven by the states’ own initiatives to increase revenues and rationalise expenditure. Yet how some of the states simply increased their revenues is the curious story of them significantly taxing liquor and, in some instances, entering the liquor trade and becoming sole retailers of liquor themselves to boost revenues. It is in this context that the levy on the liquor receipts, now common in most Indian states, merits reconsideration and a more detailed discussion.

READ I India’s fledgling e-commerce industry needs a robust policy framework

Alcohol consumption patterns in India

It is estimated that the Indian alcohol industry is one of the fastest growing industries. Consumption has been receding for several decades in countries such as the US. Last year the decline was less than 1% as liquor companies adopted strategies that are indicative of early signals that liquor consumption could now be an educated choice. Last June, giant brewer Anheuser-Busch In Bev created a role for a chief non-alcoholic beverages officer.

Faced with declining demand for Budweiser and other products, the company is investing in spiked coconut water. Other liquor companies have purchased minority stakes in nonalcoholic spirits, indicative of broad basing their offerings. The Indian alcohol industry is segmented into IMFL (Indian made foreign liquor), IMIL (Indian made Indian liquor), wine, beer and imported alcohol. Imported alcohol has a meager share of around 0.8% in the Indian market. Alcohol is exempted from the taxation scheme of GST.

By volume, India is the world’s ninth-largest consumer of all alcohol (IWSR Drinks Market Analysis). It is the second largest consumer of spirits (whiskey, vodka, gin, rum, tequila, liqueurs). India consumes more than 663 million litres of alcohol, up 11% from 2017 and more whiskey than any other country in the world – about three times more than the US which is the next biggest consumer.

Nearly one in every two bottles of whiskey bought around the world is now sold in India. If we further look at these statistics with the lens of purchasing power parity and per capita GDP numbers, it could defy socio-economic logic. Since 2001, the Indian alcohol market has registered a CAGR of 8.8% and it is expected to reach 16.8 billion liters of consumption by 2022. The popularity of wine and vodka is increasing at a remarkable CAGR of 21.8% and 22.8%, respectively. OECD reports also confirm that alcohol consumption in India has significantly risen by over 55% over a period of 20 years.

The increasing consumption of alcohol is captured by the WHO data which shows that an individual consumes about 6.2 liters of alcohol every year while the average alcohol consumption in India was 5.7 liters per person, up from 4.3 liters in 2010. Moreover, about a third of India’s population consumes alcohol on a regular basis and 11% of the Indians are moderate or heavy drinkers. One-third of males and one-fourth of females in India have made it a part of their lives, causing problems to their physical health, finances and household responsibilities.

Indians are not just drinking more; they are drinking dangerously as well. As many as 57 million people are facing the aftereffects of alcohol addiction. A survey by the Community Against Drunken Driving (CADD) revealed that over 88% of the youth below 25 years of age consume or purchase alcohol. Punjab, Goa, Tripura, Chhattisgarh and Arunachal Pradesh rank high on alcohol consumption.

Uttar Pradesh has the highest number of alcohol drinkers in India. According to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) 2015-16, in India, 29.2% of men in the age bracket of 15-49 years drank alcohol. That means that nearly one in three men in that age bracket is a consumer. The figure for women is significantly lower at 1.2%, and there are only two states where this number exceeds 10% (Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh).

READ I Scrappage policy: A big business opportunity awaits India

Background to liquor levies

The legal drinking age and the laws that regulate the sale and consumption of alcohol vary significantly from state to state, since alcohol is a subject in the State List. Just a few states are dry states which enforce a complete prohibition on sale or consumption of alcohol. Other states permit alcohol consumption and have fixed a legal drinking age for the same. This naturally precludes the practice of locally brewed liquor or illicit liquor. Recognising the market for IMFL sales, some states like Kerala and Tamil Nadu have prohibited private parties from owning liquor stores, making the state government the sole retailer of alcohol within their territories.

India has had a conflicting ideological tryst with prohibition. States have been torn between the need for revenues and the broader problems created by alcohol abuse. On certain days in the year or month, they have been imposing dry days. Some other states have gone the full hog in imposing prohibition: Gujarat (since 1960), Nagaland (since 1989), Bihar (since 2016), Mizoram (since 2019), and most parts of Lakshadweep.

Recently, Andhra Pradesh is again making liquor expensive while it works towards reducing alcoholism. Chief minister YS Jagan Mohan Reddy announced in 2019 his decision to implement prohibition in the state — a poll promise. Since then, the government has taken over the management of liquor shops and cancelled the licenses of bars while making it expensive to renew them. Whatever be the case, the largest part of Indian states’ revenues come from liquor sales.

Alcohol revenues of Indian states

In Kerala, liquor sales through the state-owned Kerala State Beverages Corporation were Rs. 55.46 crore in 1984-85. These went up to Rs 8,818.18 crore in 2012-13. At present, the entire activity of IMFL from procurement to distribution and sale is controlled by the corporation except for loose vending of liquor by bars / clubs and a small portion of the retails by Consumer Federation.

Similarly, TASMAC (Tamil Nadu State Marketing Corporation) was set up in 1983 as a monopoly liquor wholesaler for better control over distribution. For retail, it auctioned licences to the private sector. The results were stupendous — the revenues jumped from Rs 2,828 crore in 2002-03 to Rs 31,157 crore in 2018-19, probably making it top five retailer product categories.

As a percentage of the government’s own revenue, liquor assumes a significant share of the budget in most tates. The sale of alcohol has always been a major source of inflow for states — one of the reasons why the Centre never brought it under the purview of GST. The COVID-impacted economy has compelled the states to fill their coffers with alcohol tax, after their revenues were battered by several months of lockdown.

Rajasthan increased the levy by 10%, Karnataka by 11%, Delhi imposed a cess of 70% and Andhra Pradesh 75%. While sales boomed, people started to throng liquor stores, ignoring protective health measures and Covid appropriate behaviour. The southern states of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Kerala together consume as much as 45% of all liquor sold in the country. The financial position of these states was impacted as the Coronavirus lockdown completely dried up this crucial liquidity tap for them in April 2021.

States are additionally known to raise resources for specific needs from levies on alcohol. A popular scheme of providing Rs 2 kg rice scheme in 1992 in AP was funded in part from liquor levies. With public anger against rampant alcoholism, the government was forced to concede the demand for prohibition. Uttar Pradesh, had imposed a special duty on liquor to collect funds for maintenance of stray cattle.

Currently, AP is making it expensive to consume alcohol rather than experimenting with total prohibition. The state levied Additional Retail Excise Tax ranging from Rs 10 to Rs 250 per bottle making it expensive. The cost of beer has also gone up by Rs 20 to Rs 60, depending on quantity and brand. The government has issued a new policy bringing down the number of bars by 40%. In AP, the state is trying to walk a tightrope without compromising on revenue but reducing consumption. It is to be seen whether this approach will fare better than the model of complete prohibition adopted by Bihar.

Overall, the budgets are balanced by liquor receipts. To understand the significance of liquor revenues, one could look at the case of Uttar Pradesh. A few years ago, it issued a circular to all the district magistrates, directing them to check the declining liquor sale across the state. In pre-prohibition Bihar, the liberal excise policy led to liquor dens cropping up in every corner of the state. The then administration, in response to demands made by women, had stated that prohibition was not a feasible option for the state government as it earned nearly Rs 2,500 crore every year through taxes on the sale of alcohol.

Newspaper reports quoted an official as stating that “In 2014-15, the state generated revenue of over Rs 3,300 crore through liquor sales against the total revenue of Rs 25,621 crore it earned through its own taxes. The state has set a target of Rs 4,000 crore under this head in 2015-16 against the total revenue target of Rs 30,785 crore. From where would such huge money come if prohibition is implemented here?”

The story repeats itself wherever liquor sales have been resorted to as a means to bridge revenue gaps. These are the low hanging fruits for the revenue department. Ironically, what the States collect goes into developmental expenditure such as education and health. Now having built budgets on liquor revenues, the they have to take increased efforts to bottle this genie. On the flip side, at this stage, the consequences of lower revenues from liquor sales are huge: they could well result in a cut-back on government spending leading to reduced infrastructure development, social issues including unrest, inequity, etc.

An oft stated view is that in lieu of restricting sales, alcohol sale prices be raised so that they act as a deterrent. While AP will show the way in this. In fact, prices rise could most possibly result in a reduction of the household savings. To compound matters, the upwardly mobile Indian and the young India view alcohol consumption as a status statement and lifestyle necessity.

Backdoor advertising adds a touch of glamour to liquor usage. The concept of “responsible drinking” has not been promoted well! All in all, it can be broadly concluded that the Indian states have encouraged alcohol access and not balanced its social duty of citizenry health and well-being. The Bihar model can be an alternative. It has been proven that revenues from such sales are dispensable. The state has budgeted Rs 1,86,267 crore in 2021-22 as its revenue receipts, an increase of over 22% over 2019-20. Of this, 22% will be raised from its own resources.

The Gujarat budget has never relied on revenues from this source. In Gujarat, total revenue receipts for 2021-22 are estimated at Rs 1,67,969 crore, an annual increase of 8% over 2019-20. Of this, Rs 1,02,828 crore i.e. 61% comes from the states own revenues comprising Sales Tax, Land revenues, Stamp duties etc. Widening its tax base including tax on electricity etc Gujarat is a good model for an alcohol-tax free budget.

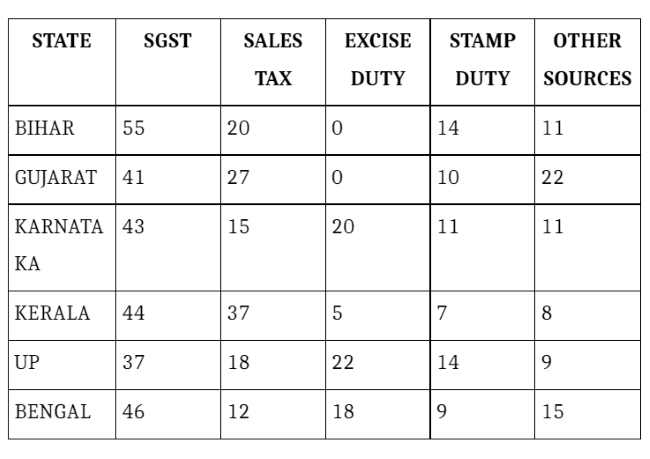

If we compare how the States fare in terms of raising internal resources which excludes borrowing, the chart below details the various levies and duties. Gujarat and Bihar both reflect ‘nil’ collections from excise duty, which is indicative of the fact that they do not gather resources from taxing liquor.

As the above table indicates, budgets can be balanced without liquor taxation. Both State and its society have mutual rights and obligations including on how public resources should be gathered and allocated. Neither can act in isolation. At the same time, it is imperative to balance the citizens’ rights in consuming products that they seek and what is legally available despite the fact that chronic alcoholism and resultant poverty can potentially result in scarce household resources getting transferred to addiction and consequent social malaise.

While revenue from alcohol appears to help in social and economic development in the short term, promoting unbridled alcohol consumption by increasing access and without informed awareness, per se, results in huge social, health and economic (including productivity) costs. With large younger demographics that India has, it is important to understand the context of this background. The crucial need, from a public health perspective, is to prevent alcohol consumption related problems. With these in mind, a greater awareness in public policy making is required along with course correction.

States should distance themselves away from lazy alcohol budgets and find other avenues to fund their activities that would entail tapping into various strengths in terms of natural, human, industrial and trade resources that they can develop. Stitching a long-term sustainable, socially conscious and responsible revenue planning should add to enhancing the strength of the social fabric. States such as Gujarat and Bihar have shown that it is possible sans alcohol.

(With inputs from Srinath Sridharan. Dakshita Das and Bhaskar Choradia are civil servants. Views expressed are personal.)