Bengaluru Metro fares and commuter behaviour: Indian cities increasingly run on a simple promise: everything, now. The same instinct that makes a 10-minute grocery delivery feel normal also shapes how urban residents value commuting time, waiting, and predictability. When the labour ministry nudged quick commerce firms to stop advertising “10-minute delivery” on safety grounds, it was not just a labour intervention. It was an admission that speed has become an organising principle, and that public policy is playing catch-up.

That shift has a less visible spillover. Stress rises, congestion hardens into routine, and commuters quietly stop behaving like the “rational” price-sensitive travellers assumed by clean microeconomic models. Bengaluru’s metro fare changes offer a useful lens. Not because the fare itself is unusually high, but because the behavioural response looks increasingly decoupled from price.

READ I Municipal finance is India’s urban faultline

Quick commerce normalises impatience

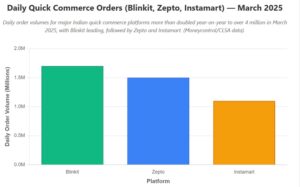

Quick commerce is not a niche service anymore. By March 2025, Blinkit, Zepto and Swiggy Instamart were together delivering over four million orders a day, with Blinkit alone at roughly 1.65–1.75 million daily orders, Zepto at 1.45–1.55 million, and Instamart around 1.05–1.15 million.

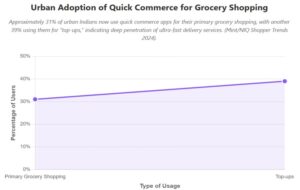

Source: Data from NIQ Shopper Trends 2024

This scale matters because it resets consumer reference points. A household that is trained to treat “waiting” as an avoidable inconvenience does not compartmentalise that preference. It carries it into other decisions: getting to work, returning home late, choosing between a predictable ride-hail pickup and a multi-leg public transport journey with last-mile uncertainty.

Policy debates that treat quick commerce as a standalone regulatory problem miss this demand-side transformation. Urban India is not only consuming faster. It is learning to dislike friction.

Source: Daily order volumes reported in March 2025

READ I Budget 2026: India needs urban governance, not big transport assets

Bengaluru metro fares: No textbook mode-shift

Standard theory would predict a fare hike nudges commuters towards cheaper substitutes: buses, cycling, walking, shared mobility. In Bengaluru, the observed pattern often runs the other way. A meaningful segment continues to buy predictability through Uber, Ola, Rapido or autos, even when cheaper public transport exists. That is not a mystery. It is a reminder that “price” is only one input into a commuter’s utility function.

The recovery of metro ridership has also been uneven across stations and corridors, with the system drawing strong volumes overall but not always translating that into seamless end-to-end journeys. The BMRCL’s 2024–25 annual reporting, referenced in public coverage, put average daily ridership at about 7.58 lakh passengers.

The more interesting question is why a fare signal struggles to discipline behaviour. The answer is found in non-price costs: time uncertainty, transfer penalties, crowding anxiety, and the perceived risk of the last mile.

READ I Budget 2026: Urban policy evolves from smart cities to City Economic Regions

The last mile is where “affordability” breaks

The evidence on last-mile behaviour is unusually clear. A WRI India working paper on metro access across Bengaluru, Delhi and Nagpur found that users, especially women, are averse to waiting; when last-mile service frequency exceeds 10 minutes, it becomes unlikely to be preferred. It also observed that women often pay more to access the metro even while travelling shorter last-mile distances, because aversion to waiting pushes them into faster, costlier options.

This is the real elasticity point. Fare changes may not move demand much if the last-mile experience remains fragile. But small deteriorations in feeder frequency, safety, lighting, or predictability can quickly erode ridership, particularly among shift workers, elderly commuters and women.

A Bengaluru survey reported in July 2025 captured the same logic from the other side: nearly 95% of private vehicle users said they would shift to public transport if last-mile connectivity were ensured.

Put together, these findings suggest that “cost” is not the main barrier for many commuters. The barrier is unreliability, and the cognitive load of stitching a trip together.

Behavioural biases make fare hikes weaker

Behavioural economics explains why price signals can look blunt in real cities.

Present bias makes immediate comfort and time certainty feel disproportionately valuable, even when the long-term financial cost is large.

Mental accounting encourages commuters to treat a daily ride-hail trip as a necessity, while treating a metro pass as a discretionary purchase that must be justified.

Default effects lock in habitual choices: once a commuter has built a routine around app-based mobility, a fare increase does not automatically trigger a re-optimisation.

Quick commerce amplifies these biases. When daily life is engineered around near-instant fulfilment, tolerance for waiting, transfers and “planning” drops. Even a well-run metro can feel rigid if the last mile is messy. The commuter is not merely buying movement. They are buying the absence of uncertainty.

What a serious policy response should target

Responses to the hikes in Bengaluru metro fares still centre on revenue, price revisions, and headline affordability. Those are necessary, but incomplete. The credible policy agenda is about reducing friction costs that commuters experience as stress, delay, and risk.

- Treat last-mile connectivity as core infrastructure, not an accessory.

Design standards should be explicit: feeder frequency thresholds, safe and well-lit walking access, enforceable service-level agreements for feeder operators, and station-area management that prioritises pedestrian flow. The evidence on 10-minute waiting aversion is not a curiosity; it is a planning parameter. - Build real integration, not poster integration.

A single ticket across metro and feeders is useful only if it removes transaction friction: unified payments, predictable interchange, and consistent information. The point is to make public transport the easy default, not the virtuous choice. - Use incentives sparingly, and only when service quality is credible.

Short-run trials, time-bound discounts, and targeted commuter offers can help break habits, but they do not substitute for reliability. Evidence from incentivisation research shows financial nudges work best when the underlying service experience meets minimum standards of comfort and predictability. - Measure commuter stress, not just ridership.

Ridership counts tell you who entered the system. They do not tell you how many people gave up because the last mile felt unsafe, or because a transfer added uncertainty they could not afford. A city serious about mode shift needs behavioural diagnostics, not just ticketing data.

Speed has changed the city’s demand curve

Bengaluru metro fares should not be treated as isolated pricing events. In a consumer-driven urban economy where speed and predictability are increasingly treated as entitlements, public transport competes on more than cost. It competes on time certainty, safety, and the mental effort required to complete a trip.

Quick commerce did not cause this shift, but it has accelerated it by normalising impatience at scale. If transport policy remains stuck in a narrow fare-and-subsidy frame, it will keep misreading commuter behaviour. Indian cities will then end up with the worst mix: expensive private mobility for households, weak public transport finances for operators, and rising congestion for everyone.

Suyasha Raikwar is 4th year BA student, and Savitha KL Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, Christ University, Bangalore Yeshwanthpur Campus.