The defining feature of the inter-war world order was not just the economic collapse. It was the simultaneous breakdown of trust between states, the weaponisation of economic power, and the retreat of leading powers from the institutions they had helped create. What followed was not immediate war, but a decade of improvisation, coercion, and miscalculation which ended in the World War II.

Donald Trump’s return to power has brought the international system closer to that condition than at any point since 1945.

This is not because American unilateralism is new. It is because, for the first time in the post-war era, the United States is dismantling the institutional scaffolding of its own primacy and demanding obedience from allies without assured return. The result is a world order that looks less like the Cold War stability and more like the turmoil of 1930s.

READ I Trump’s Board of Peace: Why the new body will lack credibility

From leadership to leverage

The post-1989 world order rested on a bargain. The US set the rules, but constrained itself through institutions it helped design. Allies accepted the situation because it came with stability, market access, and credible security guarantees.

Trump’s second-term strategy replaces leadership with leverage. Alliances are treated as assets to be monetised. Trade is redefined as a vulnerability. Institutions are tolerated only when they can be bent to presidential will. The creation of the so-called Board of Peace, a pay-to-play conflict forum chaired personally by the US president, was not a diplomatic eccentricity. It was a declaration that legitimacy would now be purchased, not negotiated.

This shift matters because it removes the predictability on which middle powers depend. When rules become optional and enforcement personal, even friendly states must hedge. That is the moment when systems begin to fray.

READ I World order in flux: Testing US power and limits

Economic coercion as default policy

In the 1930s, tariffs and currency manipulation were not side effects of nationalism; they were instruments of statecraft. The same logic has returned.

The threatened tariff regime against the European Union, the repeated use of sanctions as signalling devices rather than calibrated tools, and the casual weaponisation of market access have forced allies to rethink integration itself. The European Parliament’s decision to freeze final approval of the EU-US trade deal was not ideological defiance. It was defensive realism.

When your largest trading partner treats interdependence as a liability, the rational response is to slow integration and diversify risk. That response, replicated across multiple economies, produces precisely the contractionary spiral that defined the interwar years.

READ I US intervention in Venezuela and the Monroe Doctrine

Territorial ambiguity and alliance decay

The Greenland episode should be read less as a territorial dispute and more as a stress test of alliance norms. The United States already possessed extensive basing rights and security access under existing agreements. What it sought instead was ownership rhetoric — symbolic dominance over a NATO ally’s territory.

Europe’s coordinated economic pushback, which ultimately forced a US retreat, demonstrated something important: middle powers can still impose costs when they act together. But the episode also revealed how far norms have eroded. A threat that would once have been unthinkable had become negotiable.

That is the dangerous similarity with the 1930s. Not expansion itself, but the casual re-normalisation of expansionary talk by great powers.

State power, privatised

Another interwar echo lies in the fusion of state authority with private capital. In the 1930s, industrial policy and political proximity reshaped markets across Europe and Asia. Today’s version is more sophisticated, but the logic is familiar.

American industrial policy under the banner of national security has moved beyond regulation into selective partnership. Equity stakes, golden shares, and debt facilities tied to political networks blur the line between public purpose and private advantage. Capital adapts quickly. Risk is no longer avoided; it is priced and hedged.

For foreign firms, this creates a new calculus. Access to the US market increasingly requires political alignment or sponsorship. That is not rule-based capitalism. It is conditional participation — another hallmark of unstable systems.

Why this is not the Cold War

Cold War analogies are comforting because they imply structure. Two blocs. Clear lines. Stable deterrence.

What is emerging instead is closer to the pre-1914 and 1930s environment: multiple power centres, overlapping spheres of influence, and constant pressure on states caught in between. The historian Odd Arne Westad’s warning is relevant here. Multipolarity without strong institutions is not balance; it is volatility.

In such systems, middle powers become arenas rather than actors unless they organise collectively. Greenland is not unique. Supply chains, technology standards, minerals, and even regulatory regimes are now contested terrain.

The responsibility of middle powers

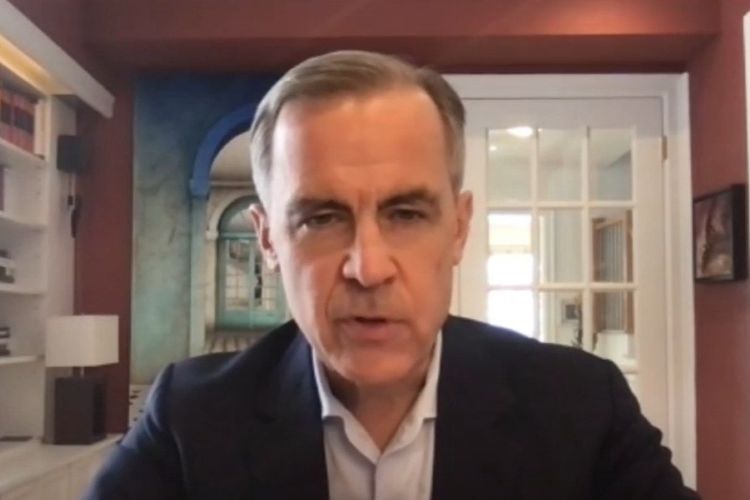

Mark Carney’s Davos intervention mattered because it named the moment accurately. This is a rupture, not a temporary deviation. Nostalgia is not a strategy. But recognition is only the first step. The lesson of the 1930s is that fragmentation accelerates when states respond individually to systemic stress. Competitive hedging deepens instability. Collective action, even if imperfect, slows it.

For today’s middle powers, that implies three priorities.

First, economic coordination beyond bilateralism. Trade diversification, shared industrial standards, and joint resource security are no longer efficiency exercises. They are risk-management tools.

Second, institutional defence. Existing multilateral bodies are flawed, but abandoning them cedes the field to ad hoc power. Reform is slower than replacement, but far safer.

Third, strategic autonomy without illusion. Detaching from American volatility does not mean opposing the United States. It means refusing dependence on unpredictability.

A narrow window

The interwar order did not collapse overnight. It eroded through a series of rational, short-term decisions that collectively proved catastrophic. By the time the danger was obvious, the machinery of restraint had already been dismantled.

Today’s middle powers still have agency. Europe’s response over Greenland showed that coordinated resistance can reset incentives. But the window is narrow. If fragmentation hardens into habit, rebuilding trust will become vastly more expensive.

The tragedy of the 1930s was not that no one saw the danger. It was that too many assumed someone else would manage it. That assumption no longer holds.