Japan interest rate hike: After three decades of ultra-easy money, Japan has begun to move—slowly, deliberately, and with global consequences. In December 2025, the Bank of Japan raised its policy rate to 0.75%, the highest level since the mid-1990s. Japanese 10-year government bond yields crossed 2%, a level not seen since 1999. Inflation, excluding fresh food, has stayed close to 3%, while the yen has weakened to a ten-month low against the US dollar.

This is not a routine tightening cycle. Tokyo has been the world’s largest exporter of capital and a cornerstone of global liquidity. Even marginal changes in Japanese yields alter portfolio decisions across advanced and emerging markets. But the pace and durability of this shift are constrained by a factor that looms over all Japanese policymaking: the country’s extraordinary public debt burden, now exceeding 260% of GDP. Monetary normalisation, therefore, doubles as a fiscal stress test. Markets know that sustained yield increases will quickly translate into higher debt-servicing costs, limiting how far the Bank of Japan can proceed without renewed intervention.

READ | India must emulate Japan’s compact city model

Why Japan interest rates matter globally

Japan’s prolonged low-rate regime enabled global investors to borrow cheaply in yen and deploy capital elsewhere. That era is ending. As Japanese yields rise, the incentives that sustained large cross-border carry trades are weakening.

The mechanics are straightforward. Higher domestic yields reduce the appeal of funding positions in yen to invest in higher-yielding assets abroad. Arbitrage opportunities narrow as interest rate differentials compress. Japanese institutional investors—among the largest holders of US Treasuries and European sovereign debt—now face a credible domestic alternative offering higher returns with lower currency risk.

Even modest repatriation flows matter. A shift out of US and European bonds puts downward pressure on prices and pushes yields higher. The result is tighter global financial conditions, steeper yield curves, and increased risk aversion—particularly damaging at a time when the US Treasury is issuing record volumes of debt and the Federal Reserve is continuing balance-sheet reduction. In this setting, Japanese capital is no longer marginal; it has become systemically important to global bond market stability.

READ | India-Japan ties enter decisive phase with 10-year plan

End of yen carry trade comfort zone

For years, the yen’s weakness amplified returns for global investors. Borrowing in yen, investing in dollar assets, and repaying liabilities in a depreciating currency was a low-risk strategy. That asymmetry is now eroding.

As Japanese rates rise, the cost of funding increases while currency depreciation is no longer assured. The carry trade becomes less forgiving. This change has implications well beyond hedge funds. Japanese life insurers, pension funds, and banks—traditionally stable buyers of overseas bonds—are likely to rebalance incrementally towards domestic assets.

Yet this rebalancing is not linear. Japan’s fiscal arithmetic places an upper bound on yield tolerance. Should rising borrowing costs threaten fiscal sustainability, markets will expect the Bank of Japan to slow, pause, or partially reverse course. That uncertainty itself adds volatility to global markets, as investors must continuously reassess whether Japan’s policy shift represents a durable regime change or a limited adjustment.

Spillovers to emerging markets

Global capital does not move in isolation. Portfolio rebalancing towards Japan affects advanced economies first, but the spillovers reach emerging markets quickly.

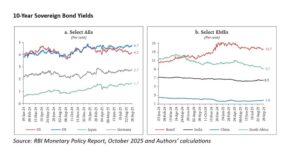

In September 2025, benchmark bond yields stood at roughly 13.7% in Brazil, 6.5% in India, 1.9% in China, and 9.2% in South Africa. These yields softened in recent months as several emerging-market central banks adopted a more accommodative stance. That relative easing now collides with tightening liquidity conditions originating elsewhere.

For India, the challenge is compounded by trade and currency linkages within Asia. Japan sits deep inside regional supply chains that feed India’s electronics, machinery, and auto-component sectors. A sustained appreciation of the yen would raise the cost of imported inputs even as it improves the competitiveness of Indian exports to Japan. The net effect is therefore uneven—supportive for some exporters, inflationary for others—revealing that financial spillovers cannot be cleanly separated from real-economy effects.

READ | Stability shaken: Japan’s economy to pay the price of political turmoil

What this means for India’s capital account

Japan has long been a stable source of foreign capital for India, both through portfolio flows and long-term institutional investment. A narrowing interest rate differential weakens that advantage. Investors can now earn higher returns in Japan without assuming emerging-market risk.

This shift could exert pressure on the rupee, especially if global risk sentiment deteriorates further. Currency volatility would complicate trade and external financing conditions. There is, however, a partial offset. A stronger yen improves the competitiveness of Indian exports to Japan by lowering prices in yen terms. For firms already integrated into Japanese value chains, this may provide incremental gains.

The larger concern lies in financial markets. Indian bond yields have shown volatility even as policy rates eased, reflecting sensitivity to global cues rather than domestic fundamentals alone. As Japanese yields rise and US borrowing needs expand, India’s capacity to insulate its bond market through domestic policy alone becomes increasingly limited.

A narrow path for policy

Japan’s monetary normalisation does not demand an immediate response from India, but it does narrow the margin for error. Global liquidity is tightening from an unexpected direction, even as headline inflation eases across many economies.

The response must be pragmatic rather than doctrinaire. Greater clarity on forward guidance, calibrated intervention to smooth excessive volatility in bond and currency markets, and continued liberalisation of foreign portfolio and direct investment rules would help anchor investor expectations. Instruments to attract stable non-resident deposits can provide buffers without distorting domestic rates.

Most importantly, policymakers must recognise that Japan’s policy turn is conditional and reversible. That uncertainty itself is the new global risk. When the world’s largest capital exporter adjusts course under heavy fiscal constraints, the effects are neither distant nor benign. India’s challenge is to remain responsive without becoming reactive.

Dr Siva Reddy is a faculty member at Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics (GIPE), Pune, and Chinmay Joshi is a Research Associate at the Economics and Policy Area at Bhavans’ SP Jain Institute of Management and Research (SPJIMR), Mumbai and a Research Scholar at Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics (GIPE), Pune.