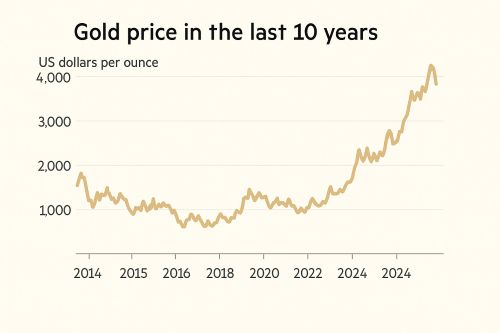

Gold price has retreated from its record high. After touching $4,381.21 per ounce on October 20, 2025, it slipped back to about $3,979 by early November. The decline has prompted the familiar question: has the precious metal run out of steam? History offers perspective. In the last half-century, every sharp upsurge in gold has been followed by long spells of sideways or weaker movement. Yet those corrections never erased the gains of the preceding boom.

The gold price began to rally in October 2022, when the metal traded near $1,617 an ounce. The ascent was modest at first, before accelerating sharply after Donald Trump’s re-election in late 2024. The three-year gain of about 170 per cent looks spectacular, but it is far smaller than earlier surges — a 518 per cent jump between 1976 and 1980, and a 643 per cent rise between 2001 and 2011. Both were followed by long downtrends, yet prices never returned to their pre-rally lows.

This pattern matters. If history repeats itself, gold may enter a phase of consolidation, not collapse.

READ I India’s climate finance strategy for COP30

Central banks fuel gold price rally

Behind the rally lies a structural shift. Central banks have been accumulating gold at a relentless pace. According to the World Gold Council (WGC), official purchases reached about 220 tonne in Q3 2025, taking year-to-date buying to 634 tonne — still far above pre-2022 levels. Even in a soft month like July, central banks added to their holdings; by August, net buying had rebounded to +19 tonnes.

Almost 95 per cent of central banks surveyed by WGC plan to expand reserves over the next year, citing diversification and currency risk. The share of gold in total global reserves has risen to the highest level since the mid-1970s.

Such official demand has created a strong floor under prices. Even after the latest correction, gold remains roughly 50 per cent higher year-to-date.

Dollar, inflation, and the fear trade

The gold price trend continues to track US monetary expectations. When real interest rates fall, gold rises. Markets now anticipate US Federal Reserve rate cuts by mid-2026, weakening the dollar and improving gold’s relative appeal. Inflation in advanced economies remains sticky, keeping investors anxious about the credibility of fiat currencies.

Forecasts differ on magnitude, not direction. UBS expects gold at $3,800 by end-2025 and $3,900 by mid-2026. Bank of America places an upper bound near $5,000 by 2026. Both assume continued central bank buying, de-dollarisation, and geopolitical uncertainty.

What history also teaches is humility: analysts rarely identify inflection points in real time. Gold’s 1970s and 2000s rallies both overshot consensus estimates before plateauing. The present cycle may behave no differently.

India’s dilemma: Reserves up, imports higher

For India, gold is both asset and liability. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) now holds over 880 tonne, valued above $100 billion, or about 15 per cent of total foreign exchange reserves. The stock has risen only marginally this year — about 4 tonnes — but price gains have inflated its value.

At the same time, India’s import appetite has grown. The country imported 64 tonnes ($5.4 billion) in August 2025, widening the trade deficit to a 13-month high in September. Every $100 increase in the global price adds roughly $400 million to the monthly import bill. The rupee, hovering near ₹ 85 per dollar, feels the strain.

Gold’s allure is not confined to households. Investment demand has shifted from jewellery to financial products. Gold ETF inflows reached ₹ 83.6 billion in September 2025, with assets under management nearing ₹ 901 billion (77 tonnes). Yet jewellery demand fell 31 percent year-on-year, showing how high prices deter consumption.

Is gold still a reliable hedge?

Gold remains the preferred refuge against monetary disorder. But the case for perpetual appreciation is weak. The WGC cautions that a rebound in the dollar or real yields could cap the rally. Indeed, after past peaks, gold did not crash; it simply drifted sideways for years. From $692 in 1980, it fell to $256 by 2001 — a 63 per cent slide that still left prices well above 1970s levels. From the 2011 peak of $1,902, gold lost 44 per cent before bottoming in 2015.

In that context, the pullback from $4,381 to $3,979 is modest. The rally is the third-largest in percentage terms over five decades, far behind the earlier manias. That suggests the metal could rise further without breaking historical precedent.

For investors, the lesson is balance. Gold is a hedge against inflation, currency debasement, and geopolitical turmoil — not a substitute for productive assets. It earns no interest, but it preserves trust when paper promises look fragile.

Policy choices for India

Three policy imperatives stand out. First, reduce import dependence. India’s households hold an estimated 25,000 tonnes of idle gold. Reviving the Gold Monetisation Scheme and expanding hallmarking and recycling infrastructure could tap this dormant wealth.

Second, deepen financial alternatives. Sovereign Gold Bonds and ETFs allow savers to benefit from price gains without drawing down foreign exchange. The government should publicise these products as inflation hedging tools rather than speculative assets.

Third, manage reserves with prudence. The RBI’s growing gold share diversifies risk, but valuation swings can distort reserve metrics. A balanced mix of gold, foreign currencies, and IMF SDRs will protect stability.

Beyond these, communication is crucial. Policymakers should remind investors that gold’s virtue lies in steadiness, not excitement. A temporary retreat should not provoke panic, nor should a fresh surge encourage complacency.

The current gold price correction may look dramatic, but in historical context it is routine. The metal’s long-term uptrend remains intact, supported by central bank demand and global uncertainty. What follows is likely to be a period of consolidation, not collapse. For India, the challenge is to harness gold’s financial potential while containing its macroeconomic risks. A coherent policy — combining monetisation, digital gold, and calibrated imports — can turn volatility into strength. Gold may rest, but it has not lost its lustre.