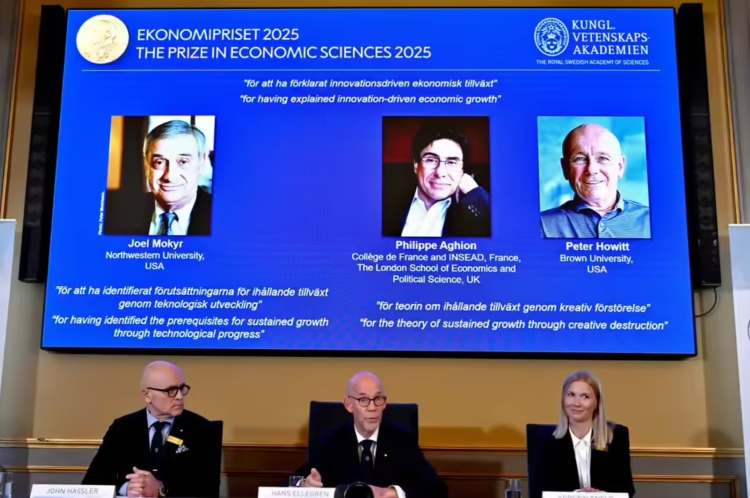

Economics Nobel rewards theory of innovation-driven growth: A 2025 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences has spotlighted a central question: how can growth become self-sustaining in a modern economy? Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt have been honoured precisely for bridging innovation, history and theory to explain that link. Yet the acclaim should not preclude critical scrutiny. Their contributions are indispensable, but also subject to limitations and caveats.

Joel Mokyr has long argued that technological innovation alone is not sufficient to trigger sustained growth; rather, the institutional, cultural and intellectual environment must permit the transmission, evaluation and cumulation of useful knowledge. In A Culture of Growth, he insists that modern growth was premised on a belief in progress, a “republic of letters” committed to open inquiry, and an institutional ecology that tolerated heterodox ideas. His work thus restores agency to unpredictable cultural shifts—something that purely mathematical models tend to suppress.

Role of institutions in Mokyr’s framework

By emphasising the non-economic constraints on innovation, Mokyr’s framework warns that growth can founder on institutional sclerosis even when incentives exist. His historical calibration shows that innovation was not regularly transformative prior to the eighteenth century because the “machine” of cumulative science and technology was fragile.

Critics, however, caution that Mokyr may over-emphasise the weight of “extraordinary individuals” or elite networks. Geoffrey Hodgson, for example, suggests that Mokyr places “too much explanatory weight” on a few pivotal thinkers rather than more diffuse institutional change. Moreover, the task of converting Mokyr’s cultural categories into operational variables in empirical growth regressions remains hard. The mechanism by which “culture of growth” shifts endogenously in a modern economy is underspecified.

READ I Trump’s China tariff threat is more bluff than battle

Aghion–Howitt and creative destruction

While Mokyr anchors the necessary, almost macro-cultural groundwork, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt supply the engine: a formal model of creative destruction. Their 1992 seminal paper, A Model of Growth Through Creative Destruction, introduces a growth process in which new vertical innovations displace old technologies, rendering obsolete prior capital, skills, and industries.

This framework transforms Schumpeter’s metaphor into a tractable structure. It explains how growth may remain perpetual, as firms constantly vie to innovate, displacing incumbents, but also generating welfare losses (from obsolescence, job displacement, and waste). Crucially, laissez-faire outcomes may undershoot optimal innovation because innovators internalise few of the social spill overs or externalities.

From this model flowed a large literature exploring the role of competition, firm dynamics, and optimal policy: when should subsidies to R&D be granted, how to manage transitions, and how to cushion the displaced.

Yet limitations are visible. First, the model is stylised: innovation is treated as a one-dimensional process; the heterogeneity of sectors, complementarities across technologies, and network effects are simplified or omitted. Second, the assumption that innovation always supersedes older technologies may exaggerate the coherence of replacement dynamics. Third, Aghion–Howitt’s model struggles to explain why some economies stagnate despite having incentive structures theoretically favourable to innovation (a “growth trap”).

Finally, the endemic critique of endogenous growth more generally — its reliance on unobservable spill overs, weak micro foundations, and difficulty in explaining convergence — applies. As Wikipedia notes, “too much of it involved making assumptions about how unmeasurable things affected other unmeasurable things.”

Aghion himself, with co-authors, has since refined the theory (for instance, by introducing an “appropriate growth institutions” perspective) in What Do We Learn from Schumpeterian Growth Theory? But even so, reconciling theory with heterogeneous real economies remains a challenge.

Economics Nobel for innovation-growth policy nexus

One virtue of the trio’s work is that it constitutes more than ivory-tower abstraction: it provides policy levers. The Nobel committee stressed that their insights could help steer growth through science policy, competition regulation, openness, and institutional design.

Aghion in particular has been active in public policy domains: he co-chaired a French commission on artificial intelligence, and emphasises that innovation must be balanced by competition policy (to prevent superstar firms stifling new entrants). He warns against protectionism and deglobalisation as threats to the exchange of ideas and scale effects. Mokyr, echoing this, cautions that any policy that discourages immigration may harm innovation, while authoritarian states may undermine academic openness.

The policy message for a developing country is clear: build institutions that value science, ensure inclusive mobility of talent, maintain openness to trade and ideas, and cushion the social costs of disruption. But the translation is far from trivial. How should subsidies be structured across sectors? How to calibrate regulation to allow daring innovation without runaway externalities? How to manage inequality and displacement? The trio’s models and historical interpretation point to these questions but seldom yield ready blueprints.

Culture, equilibrium, and stagnation

Juxtaposing Mokyr’s cultural insight and Aghion–Howitt’s formal machinery reveals tensions as well as synergy.

Causality and feedback loops: Mokyr insists that culture and institutions enable innovation; Aghion–Howitt treat innovation as endogenous but within a given institutional envelope. The feedback from innovation back into institutions is harder to model.

Equilibrium bias: Mathematical models tend to drift toward steady states; historically, growth trajectories are punctuated, path-dependent, occasionally derailed. Mokyr’s historical method better accommodates breaks and reversals.

Stagnation traps: The trio’s framework reminds us growth is not automatic, but neither fully addresses why some regions remain locked in low innovation equilibria despite plausible policy reforms.

Inequality and distribution: Creative destruction is disruptive. Who benefits, who loses? The trio’s framework is weaker on redistribution, social safety nets, and political economy.

The contributions are complementary but not seamlessly integrated. The historian warns of social drag; the theorist gives the engine; the policymaker struggles to connect them in messy real economies.

Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt together have deepened the edifice of growth economics. Mokyr restores the human, cultural and institutional precursors for sustained innovation; Aghion and Howitt formalise the process of creative destruction in ways that can be confronted with data; and all three point toward policy levers to reinforce growth. Yet their work invites critique: the challenge of operationalising culture, the limitations of stylised models, and the gap between theoretical clarity and messy policy design.

For emerging economies—India among them—their message is stark: growth must be engineered not only via capital and incentives, but by cultivating institutions, tolerating disruption, and steering human talent. If stagnation is not the default, it is a risk. The task for policy is to safeguard the “engine room” of innovation even as it tempers its turbulence.