State debt mounts: There was a time when Indian states borrowed primarily to finance growth — building roads, irrigation systems, schools, and hospitals. That pattern has changed. Increasingly, debt has become a lifeline to plug fiscal deficits, fund welfare outlays, and roll over legacy liabilities. According to the Reserve Bank of India, states plan to raise ₹2.82 lakh crore in the current quarter alone — a scale that raises fresh concerns about the sustainability of subnational debt.

Economists have long cautioned that several states, including Punjab, Bihar, Nagaland, and Kerala, are straying from fiscal prudence. Others, such as Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Telangana, continue to use debt as a lever for development rather than dependence. The divergence between these two groups has deepened, making state debt simultaneously a matter of concern and confidence — depending on which balance sheet one examines.

READ | India’s electric vehicles push gains global momentum

Rising state debt ratios and fiscal stress

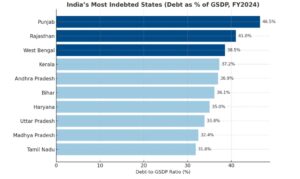

State development loans are the main instrument of borrowing, intended for long-term developmental spending on infrastructure, health, and education. But increasingly, these loans are being used to fund revenue expenditure. The RBI’s ‘State Finances: A Study of Budgets 2024-25’ projects that aggregate state debt will hover at 28.7% of Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) this year — dangerously close to the 30% ceiling recommended under the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) framework.

Post-pandemic pressures have worsened the asymmetry. Some states have managed to preserve fiscal space thanks to buoyant manufacturing and service-sector revenues. Others suffer from what the RBI calls a “quality of expenditure” problem — too little investment in productive assets and too much in recurring commitments.

Punjab, for instance, has a state debt-to-GSDP ratio exceeding 46%, the highest among states. Nearly a quarter of its revenue receipts are consumed by interest payments. Kerala’s fiscal stress is structural, driven by high committed expenditure and weak tax buoyancy. These numbers reflect widening regional fiscal inequality.

Another drag on state budgets is the steep rise in committed expenditure — salaries, pensions, and interest payments — which now absorb nearly two-thirds of total revenue receipts. Pensions alone account for over 12% of state revenues, and the trend is worsening as several governments revert to the fiscally unsound Old Pension Scheme (OPS). Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, and Himachal Pradesh have already rolled back the National Pension System, a move that could add up to one percentage point of GSDP to their liabilities over time. These obligations leave little room for capital investment, forcing states to borrow not for future assets, but to service past promises.

A large part of the state debt burden stems from their growing dependence on central transfers and the unpredictability of devolution. The Union government’s decision in July 2024 to release half of the year’s tax devolution in one tranche — amounting to ₹1.2 lakh crore — underscored both the urgency and fragility of state budgets.

Over the years, successive Finance Commissions have redrawn the revenue-sharing formula, tilting allocations in favour of population-weighted states in the north. This has left fiscally responsible states such as Kerala and Tamil Nadu grappling with declining shares of divisible tax revenue. Add to this the tapering of centrally sponsored schemes and delayed grants-in-aid, and states’ fiscal space has shrunk just when their expenditure needs are growing fastest.

Borrowing for growth vs borrowing for consumption

Borrowing is justifiable when it funds capital assets — roads, power grids, renewable energy, irrigation, and healthcare systems — that expand productive capacity. It is far less defensible when used to finance salaries, subsidies, or populist giveaways. Yet in recent years, the distinction has blurred. Many states now use debt to fund cash transfers, farm loan waivers, and power subsidies — policies that are politically popular but fiscally corrosive.

A recent study by the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP) found that nearly 40% of state borrowings in FY24 financed revenue expenditure rather than capital formation. This is a red flag for long-term fiscal sustainability.

Rising borrowing costs and market concerns

According to the RBI’s market calendar, the second half of FY25 will witness one of the heaviest state borrowing programmes in recent memory. The central bank has urged states to stagger issuances to prevent bunching and elevated yields. Yet, State Development Loan yields have already begun inching up as investors grow wary of subnational credit risk.

When a few states exceed borrowing limits or delay repayments, the contagion effect pushes up borrowing costs for all. Fiscal indiscipline, in short, is infectious.

Reforming fiscal federalism

Austerity alone cannot fix the problem. States account for nearly 60% of India’s public capital expenditure, and throttling their borrowing could cripple national growth. The answer lies in ensuring that every borrowed rupee yields measurable development outcomes.

Tamil Nadu offers an example by strengthening its debt management office and improving project evaluation. Maharashtra has introduced fiscal risk statements and medium-term expenditure frameworks. Linking borrowing to outcomes — through performance-based budgeting and transparent disclosure — can help restore credibility.

Transparency, however, remains patchy. Off-budget borrowings — loans raised by state entities or guarantees extended to power utilities — remain largely opaque. The RBI estimates that hidden liabilities could add 2–3% of GSDP to the state debt burden of some states. Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, and Telangana carry large exposures through power-sector guarantees. The Centre’s 2022 decision to include such borrowings under FRBM limits was a step forward, but compliance remains inconsistent.

States must publish comprehensive debt disclosure statements, including details on guarantees, contingent liabilities, and public-private partnership (PPP) commitments.

Restoring fiscal autonomy and responsibility

With the expiry of GST compensation grants, many states have seen their fiscal autonomy shrink. To restore buoyancy, states must expand their tax bases — through better property tax collection, rational user charges, and digitalised compliance. At the same time, fiscal responsibility laws must evolve to allow counter-cyclical spending without endangering long-term solvency.

The deeper issue, however, is political. Populist schemes — from free electricity to cash transfers before elections — are politically expedient but economically unsound. The RBI has repeatedly warned that such giveaways heighten fiscal risks and delay the process of consolidation. India cannot afford to slide into the debt traps witnessed in Sri Lanka or Pakistan.

Debt, by itself, is not the enemy. Used prudently, it can build assets and generate growth. The danger lies in using it as a substitute for reform or restraint. India’s fiscal health will depend not on how much states borrow, but on how wisely they spend.

The path forward lies in aligning ambition with realism — ensuring that every rupee borrowed today strengthens, rather than mortgages, the future.