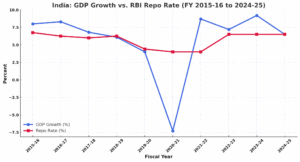

RBI monetary policy review: The new GDP print—6.5 % for FY 2024-25—arrived on 30 May with little fanfare and even less cheer. At that pace, India will fall woefully short of its own ambition: to lift per-capita income from roughly $2,880 today to $17,000 by 2047. Simple arithmetic says incomes must rise by more than 8% a year for 22 straight years; headline GDP, therefore, has to motor along at around 9%, given the modest growth in population. The current growth path is not a mere statistical shortfall—it can weigh on India’s development ambitions.

Some policy makers feel that sustained high growth is impossible in the current global context. History disagrees. South Korea, battered and resource-poor, clocked nearly 8% between 1962 and 1989; China averaged double digits from 1980 to 2010. Both countries did this while oil shocks, recessions, Asian financial turmoil and the birth—and death—of hyper-globalisation raged outside their borders. The lesson is blunt: decisive policy can drive Indian economy towards take-off.

READ I RBI to target core inflation in monetary policy reset

A faltering engine room

Beneath the aggregate numbers lie worrying trends. Real gross value added in manufacturing collapsed from 12.3% last year to 4.5%. Electricity, construction, and financial services also lost momentum. Coal, crude, cement, steel consumption, vehicle sales, port cargo and airport passengers—all the nimble indicators of real-time demand—are decelerating. The Index of Industrial Production shows red ink across mining and an uncomfortable range of factory lines, from rubber and plastics to machinery and automobiles.

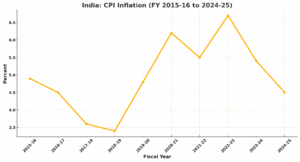

Inflation is the lone bright spot. Headline CPI cooled to 3.16% in April; food inflation is a negligible 1.78%. Wholesale prices have stayed subdued for months. Oil, hovering at $63–65 a barrel, has refused to misbehave, and reserves of $691 billion—11 months of imports—buffer the rupee. Yet low inflation alongside slack private investment is a reminder that demand, not supply, is the binding constraint.

Banks are flush; borrowers, not so much

Indian banks booked record profits in FY 25, helped by treasury gains and lower bad-loan provisioning. Deposits have drifted into fixed-rate buckets, and credit growth has tapered. A risk-averse financial system, awash with liquidity but shy of new borrowers, is a powerful brake on animal spirits.

Capital outlays by government have pushed gross fixed capital formation up to 33.7% of GDP, yet the private share of that pie is shrinking. Public investment can crowd in private capital—but only if the return calculus looks attractive. At the moment it does not.

What the MPC cannot duck

The RBI forecasts another 6.5 %year in FY26 while projecting CPI at a comfortable 4%. A benign price path gives the Monetary Policy Committee room to move. History suggests that unless real rates fall decisively—and stay there—boardrooms will not reopen their cap-ex spreadsheets. Housing, autos, construction materials, commercial vehicles: every big-ticket purchase in India is interest-sensitive. The signal needs to be clear.

Cut the policy rate by 50 basis points now, and telegraph a bias to do more unless inflation threatens to rip. That is the minimum down-payment on 9% growth.

The strategic pivot RBI needs

The RBI’s inflation target of 4% ±2 % sits uneasily with India’s three-decade average of around 6%. By squeezing tolerance bands too tight, policy risks throttling the investment cycle, employment and the demographic dividend that will fade in two short decades. Better a clear, credible 5–6 % corridor that matches long-run realities than a sanctified 4 % that condemns the economy to under-performance.

Switching the policy anchor from headline CPI to core inflation—stripped of food and fuel—may look like an elegant way for RBI to duck the inevitable tomato-and-onion spikes that torment Mint Street each monsoon, but elegance can be costly. Core inflation, by design, filters out the very price movements that batter households and shape popular expectations; when policy makers pretend the kitchen budget does not matter, they risk losing credibility faster than they gain analytical tidiness.

The policy pivot must be three-pronged: first, push real borrowing costs below expected returns by loosening the policy rate and letting banks price credit competitively rather than defensively; second, deploy public capital expenditure as a magnet for private money—roads, digital networks and clean power grids that make boardrooms reach for cheque books instead of excuses; and third, reset the inflation anchor to a credible 5–6% corridor so that businesses can plan, workers can bargain and households can spend without fearing a sudden monetary U-turn.

All these steps are urgent. If India wants the mantle of Viksit Bharat by 2047, it must swap comfort for conviction. The window is open now—and, like all demographic windows, it will not stay open for long.

Dr Charan Sigh is a Delhi-based economist. He is the chief executive of EGROW Foundation, a Noida-based think tank, and former Non Executive Chairman of Punjab & Sind Bank. He has served as RBI Chair professor at the Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore.