US-UK trade pact skirts key topics: On the 80th anniversary of Victory Day, President Trump and Prime Minister Keir Starmer announced what both leaders called a historic trade pact. It was heralded in Washington as a triumph of Trump’s uncompromising trade strategy, and in London as a lifeline for beleaguered industries. But beneath the soaring rhetoric and ceremonial pronouncements, the deal is best described not as a transformative free trade agreement, but as a narrowly framed economic détente—a ceasefire of sorts in an increasingly fragmented global trade order.

Yes, the US-UK trade pact brings relief to British steelmakers, car manufacturers, and a segment of the American agricultural lobby. Yet, it fails to answer the foundational questions: Can trade diplomacy function under duress? And can two mature economies deepen ties when trust is replaced by transactionalism?

READ I India-UK FTA will boost jobs, exports and strategic ties

A deal of quotas and quiet concessions

At the heart of the US-UK trade pact lies a carefully calibrated quota regime. The United States will allow up to 100,000 British-made vehicles—mostly luxury cars—to enter under a 10% tariff. Any volume above that faces the full 25% Trump-era levy. For an industry that exported over £9 billion worth of cars last year, this is partial reprieve, not liberation.

Similarly, British steel and aluminium are granted full tariff exemption, lifting a weight off a sector teetering on the brink. In exchange, the UK will welcome tariff-free imports of 13,000 metric tonnes of U.S. beef and 1.4 billion litres of ethanol—moves that are already drawing protests from British farmers worried about the viability of domestic agriculture and the precedent it sets.

And therein lies the design: tit-for-tat bargaining under a populist microscope, not the architecture of a long-term strategic partnership.

US-UK trade pact: Narrow path for broader gains

Even as Trump and Starmer strike celebratory tones, economists and trade experts have been less effusive. The deal reveals “rising desperation” within the White House to avert economic blowback from escalating tariffs. The changes are pretty narrow—a rebranding of the status quo rather than a reset.

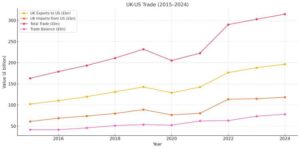

More revealing is what’s absent from the agreement: no rollback of the 10% baseline tariff imposed globally by the US; no breakthrough on services trade, despite the fact that Britain exported £137 billion in services to the US last year—more than double its goods exports; and no resolution on digital services taxes, which continue to antagonise Big Tech and their Capitol Hill patrons.

Worse, there is no mention of exemptions for pharmaceuticals or the film industry, both vital UK exports, now threatened by Trump’s next round of tariffs. This isn’t so much a negotiation as a game of economic triage.

Agriculture remains the most politically sensitive—and uneven—terrain in US-UK trade. While the American Farm Bureau Federation called the deal an important first step, the UK’s National Farmers’ Union expressed grave concern. Its president, Tom Bradshaw, lamented that British farmers are being “singled out” to shoulder the burden of tariff concessions for other industries.

The compromise to allow beef trade—within strict food safety norms—has done little to quiet the disquiet. US producers gain access to a lucrative foreign market while British arable farmers brace for the impact of tariff-free ethanol. If the US-UK trade pact’s litmus test is balance, this section fails it outright.

A framework in name, fragmentation in spirit

The White House has framed the US-UK trade pact as part of a broader Economic Prosperity Deal, aligning it with Trump’s so-called America First doctrine. For Trump, the win lies not in the details, but in the declaration—a televised event, a headline, a validation of unilateralism repackaged as bilateralism.

For Starmer, the US-UK trade pact comes with political dividends. It provides a respite from domestic economic turbulence and a counternarrative to protectionist drift. But it also exposes the UK’s vulnerability in a post-Brexit world, where it races to keep pace with a trade order being redrawn by executive fiat, not multilateral consensus. The bigger prize—an enduring, comprehensive FTA—remains elusive.

The economic impact: Modest and uneven

Despite its “historic” billing, the economic boost from the pact is likely to be modest. Analysts at JP Morgan caution that the “still-uncertain global backdrop” will blunt any short-term gains. UK growth forecasts have already been downgraded in response to tariff-induced uncertainty, and this agreement—limited to select goods—does little to change that.

The Bank of England’s recent rate cut to 4.25% underscores the fragility of Britain’s recovery. Tariff reprieves may lift sectoral sentiment, but they cannot substitute for a broader industrial revival. Nor will they insulate the UK from global shocks, particularly as tensions escalate with China, where the real trade war—and the greater economic risk—lies.

A diplomatic win, strategically thin

That Britain is the first country to strike a trade deal under Trump’s second term is significant. It signals to other nations that Washington’s tariff regime is pliable—but only through ad hoc, high-pressure diplomacy. It’s an invitation to negotiate, yes, but under terms dictated not by mutual interest, but presidential mood.

This is a departure from the old liberal order. No WTO framework, no multilateral guardrails—just bilateralism with strings. If the objective was to promote “economic security,” the result is instead selective appeasement.

To be clear, the US-UK trade pact is not without merit. Jobs will be protected, markets will open incrementally, and strategic industries like aerospace will benefit from smoother supply chains. But let us not pretend this is a game-changing accord. It is a short-term patch, not a policy platform.

What the US-UK relationship needs is a return to principled trade engagement—anchored in predictability, comprehensiveness, and equity. What it currently has is a fragile arrangement that speaks volumes about the imbalance of leverage and the impermanence of handshake diplomacy. Unless the next chapter addresses digital services, pharmaceutical tariffs, and the broader services trade imbalance, this agreement will remain what it is: a photo-op posing as policy.