Income-share agreements vs education loans: The academic community is still debating ‘what should be taught to the young generation’ even after almost 75 years of independence. The idea is to sanctify the essence of human needs and values. This debate has become intriguing at a time when several reports suggest that 85% of the jobs that will be available to the Generation Z are yet to be invented. The fast-paced changes in technology will see several such disruptions in the coming years.

Skilling, upskilling and reskilling of this generation have become an urgent need to combat the uncertainties. However, the higher education institutions have their own limitations in terms of consistently upgrading the curricula in line with the demand and supply dynamics of the labour market.

The National Education Policy (NEP 2020) has addressed the very purpose of education. It states: “to develop good human beings capable of rational thought and action, possessing compassion and empathy, courage and resilience, scientific temper and creative imagination, with sound ethical moorings and values”. Therefore, quality higher education in today’s world must strive to create more vibrant, socially engaged, cooperative communities and a happier, cohesive, cultured, productive, innovative, progressive, and prosperous nation.

READ I Public health policy must focus on non-communicable diseases

All these values can be imbued via higher-order cognition proposed by NEP 2020 which includes the capacities for self-directed independent learning, critical reading, critical thinking, rational inquiry, innovative problem-solving, and clear, precise, and effective communication. These skill sets are more perennial and less volatile, and can be addressed by designing and implementing the curriculum. The same is not true with the skill sets for employability or economic well-being which are more volatile. Now the question is how it can be addressed?

Historically, investment for nurturing human capital and capabilities through building and strengthening research and development has been the most powerful weapon to combat uncertainties of all kind. Over time, the government of India has realised this and has taken several steps. But the effort has, so far, been inadequate. The government has its own budgetary limitations to match the needs of the country’s enormous workforce.

Challenges in funding higher education

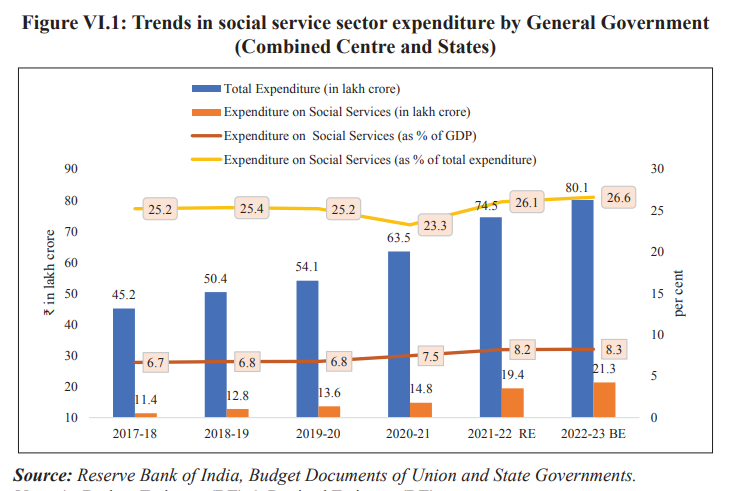

Over the years, India’s expenditure on research and development to the GDP has virtually remained stagnant in the range of 0.56%-0.70% which is less than the global average of 1.80%. Even the spending on education has remained stagnant over the last many years. The data on educational expenditure suggests that it has been 2.8 to 3.5 % of GDP over the last decades. Although, several committees including the committee on NEP recommended 6% of GDP, the government’s fiscal situation cannot afford that kind of spending. Over the years, the government spending on education as a percentage of total expenditure has been in the range of 8.5-10.8%.

Over the next few decades, India will have the highest young population in the world. So, the future of the country will be determined by the quality and magnitude of educational opportunities for its young population. The current data suggest that the proportion of skilled workers is extremely low — 4.69% of the total workforce compared with 24% in China and 52% in the US. This is India’s position at a time when we have the world’s largest higher education system with about 1,000 universities and 40,000 colleges. Therefore, it demands serious policy interventions.

Government’s corrective steps

The government is taking corrective action by balancing inclusion and excellence. The fund allocation to the education sector in this year’s budget is the highest ever. Skill development has been the subject of special attention over time. The establishment of National Digital University, as envisioned by NEP (2020), has very strong potential to skill, reskill and upskill the youth.

The budget 2023 has announced the revamp of the government’s flagship skilling scheme, the Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY 4.0). Under this scheme, emphasis is given to skilling lakhs of youths through on-the-job training, industry partnership and alignment of courses with need of the industry. The scheme also covers new age courses for Industry 4.0 like coding, AI, robotics, drones, and soft skills. To skill the youth for international opportunities, an announcement is made to set up 30 Skill India International Centres.

Allowing FDI and external commercial borrowing in higher education; constituting the higher education commission (HEC) for accreditation and regular funding of colleges and universities; allocating Rs 50,000 crore to National Research Foundation (NRF) to boost the quality and quantity of research; implementing New Education Policy (NEP); and collaborating with foreign countries are such initiatives taken in this direction in recent years.

The government has its limitations as far as the allocation of funds are concerned. The government must maintain the balance between fiscal prudence and the funding needs across various schemes. But this cannot be the rational logic when competing with the rest of the world to combat volatilities, uncertainties, complexities and ambiguities. Hence, India needs to look beyond the budget allocation and government expenditure if it were to win the race.

Policy interventions needed

The government should focus on some parallel self-interlocking mechanism where an investor can invest in an individual’s future earnings, unlike an education loan. Therefore, the government should incentivise such start-ups and design policies for an inductive ecosystem where such business entities can profit from skilling, upskilling and reskilling.

India has benefited from the efforts by the government. For a long time, the country has been dependent on government expenditure to improve the education sector. It is high time to look beyond this, and there is an urgent need for a shift in policies but not at the cost of the deprived sections. The vulnerable, the poor, and the deprived sections of the population should remain the responsibility of the government.

Income-share agreement: A smart alternative

The current situation reminds us of Nobel prize-winning economist Milton Friedman’s 1955 essay on the role of government in education. He argued for equity investment in an individual’s future earning prospect- income share agreements. He wrote, “Investors could buy a share in an individual earning prospects to advance him the funds needed to finance his training on the condition that he agrees to pay the lender specified fraction of his earnings. In this way, a lender would get back more than his initial investment from relatively successful individuals, which compensate for the failure to recoup his original investment from unsuccessful”.

It works like this. If a student wants to enrol in an institution but doesn’t have the money to do so for want of collateral, the school will intervene and find a way to pay for their education. This is done under the proviso that if the student graduates and secures a job with a certain salary, he or she would be required to pay back a portion of monthly income with the institution.

Income-share agreement is an alternative to education loans where repayments are based on a student’s future income. The service provider funds the college education of a student who agrees to pay the provider part his/her salary for a period of time. Globally, the rate is 2-10% of the student’s future income. That means the higher the salary, the higher would be the ISA payment. Unlike loans, there is no interest payment involved in the case of ISA funding.

It is worth emphasising that income-share agreement becomes fully functional only if the student earns a minimum salary after finishing the programme. When a student’s income falls below a certain threshold, they are exempt from making repayments. The same applies to joblessness. In this way, the new innovative methods of funding ease the burden placed on students, unlike in the case of education loans, while simultaneously resolving the issue of social-economic disparity in higher education. Therefore, ISA could be a source of financing where the investor’s interest lies in the student’s growth.

Ultimately, the institution must impart the requisite skills and match market demand in order to place students. Otherwise, its funds will be lost without a return. Under ISA, students have no legal obligation to work in a specific industry. It is illegal for investors to coerce them into a particular job. Such nature of its functioning eliminates the possibility of indentured servitude.

Some Startups like AttainU, InterviewBit, Pesto Tech and AltCampus are offering the income-share agreement model in India. Parallelly, we need to develop an ecosystem where an investor can also explore the possibility of rational investment in this sector.

(Dr Shashank Vikram Pratap Singh is Assistant Professor at Shri Ram College of Commerce, University of Delhi.)