The delicate balancing act between the demands of welfare schemes and maintaining prudent fiscal management has always been a challenge for India’s political leadership. During election seasons, politicians often make extravagant promises to sway voters, frequently disregarding the government’s financial constraints, exacerbating the fiscal deficit. The recently elected Karnataka government wasted no time in announcing free bus ride for women and free electricity up to 200 units, a strategy that has found favour among voters. While these initiatives seek to alleviate financial hardships for women and the needy, it is vital to recognise that they come at a significant cost to public finances.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has cautioned against the culture of freebies, which he referred to as the ‘revari culture.’ However, during elections, his own party often ignores this warning. The root of the issue lies in the absence of a clear distinction between freebies and welfare schemes, exacerbated by the lack of a legal framework to differentiate between the two. While some of these offerings genuinely enhance the welfare of citizens, many do not bring about any substantive improvement. Failing to distinguish between welfare schemes and freebies can have severe repercussions, as politicians frequently exploit this ambiguity as an effective election strategy.

READ I Cartels to face heat from Leniency Plus rules

Why welfare schemes

Welfare schemes are designed to promote social equality by providing access to essential services for low-income, marginalised, deprived, and elderly populations. Examples of welfare schemes include the public distribution system, which offers essential commodities, and healthcare initiatives such as the Ayushman Bharat Yojana, which provides health insurance benefits. In contrast, freebies target a broader audience and seek to achieve specific objectives, often involving tangible goods like laptops. In essence, welfare schemes aim for long-term economic stability and sustainable development, while freebies provide immediate short-term benefits.

It is essential to evaluate the positive aspects of freebies and ensure they contribute to legitimate public spending. India has implemented several economic and social reforms to achieve this goal, introducing policy measures that can be considered legitimate freebies. For instance, the public distribution System (PDS) provides free or subsidised essential commodities, while subsidised employment programmes like MGNREGA guarantee rural households a certain number of days of wage employment.

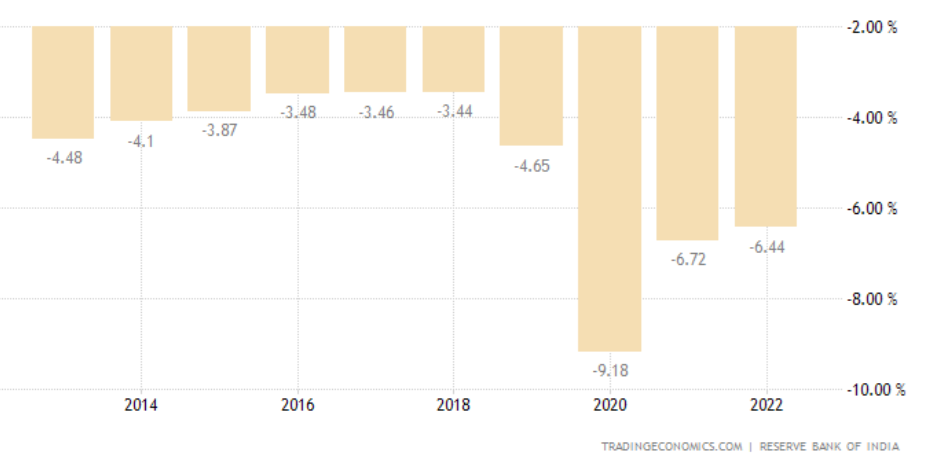

Fiscal deficit of Union government

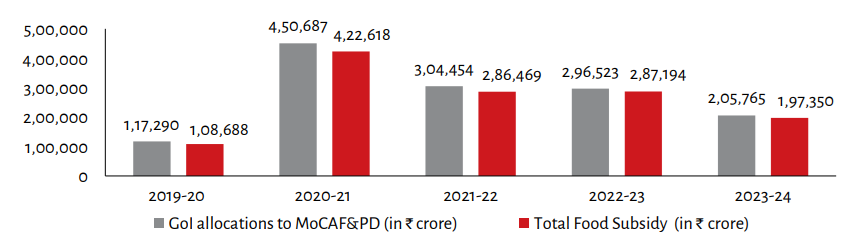

Union budget allocation for food subsidy

Income transfer schemes like the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) promote financial inclusion and uplift disadvantaged communities socioeconomically. However, such freebies require substantial funding, impacting the fiscal balance of states. Therefore, freebies must align with long-term development goals, or else states may bear significant financial burdens that hamper their fiscal capacity.

The downside of government subsidies is that they come at a cost, affecting various consumer categories, and potentially resulting in revenue shortfalls if not offset by the government. Consider the electricity sector in India, which serves industrial, agricultural, and household consumers. Unequal tariff setting leads to varying payments among these groups, resulting in cross-subsidisation driven by social justice but often exploited for political gain.

This distortion in pricing leads to neither group paying the correct price for power, creating revenue shortfalls. When states borrow to provide free electricity and compensate distribution companies, it increases their public debt and interest payments. Several Indian states, including Punjab, Andhra Pradesh, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Kerala, Haryana, and Bihar, have been identified by the Reserve Bank of India as facing significant financial burdens due to their expenditure on free utility distribution to influence elections.

A critical dilemma arises when discussing the allocation of funds between freebies and welfare schemes in the education sector. Although Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman has clarified that investments in education services should not be categorised as freebies, literacy rates in states like Punjab, Rajasthan, and Andhra Pradesh remain below the national average despite efforts to provide free education and improved infrastructure.

The truth is that politicians’ tendency to provide freebies to secure voter support can lead to financial catastrophe for states. Increased expenditure on free services and schemes escalates states’ debt levels, constraining their ability to secure additional funds from the market and the central government due to their weakened financial health. Sri Lanka’s recent financial crisis serves as a cautionary tale for Indian states distributing free goods and services to attract voters, further compromising their financial stability. Unless states recognise these potential consequences, they are teetering on the brink of experiencing the dire repercussions of unchecked freebie distribution.

The trend of politicians embracing the “revari culture” should be approached with caution, as it may prove unsustainable in the long run. While some positive outcomes, such as improved infrastructure and expanded access to education and healthcare, may result, states often allocate resources beyond their capacity, resulting in unsustainable schemes and services.

To ensure the fiscal sustainability of such programmes, support for freebies should be limited to a predetermined percentage of both central and state government expenditures, pending improvements in revenue ratios. Effective allocation of resources for welfare schemes should involve a careful assessment of income and price elasticity as key indicators. Ultimately, prudent fiscal management must walk hand in hand with the goals of social and economic convergence.

(Abhishek Seth and Swayamshree Barik are PhD students in Economics at the Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee. The food subsidy graphic is from a CPR report.)