Countering US tariff threat: The United States has imposed a sweeping 50% tariff on Indian exports, citing “strategic recalibration” and “domestic industry protection.” The reaction from markets and media was predictably grim: forecasts of collapsing exports, strained foreign reserves, and dark warnings of a looming economic crisis. But this widespread anxiety misses the mark. This tariff may turn out to be a historic opportunity, just like in 1991 for India—a catalytic shock that compels India to do what it should have done decades ago: invest in itself.

The Indian economy, long fixated on export-led growth, now has the chance to pivot decisively towards building internal capacity, expanding domestic demand, and strategically guiding credit creation to fuel the funding for national development. This is not a time to retreat. It is the moment to unleash the full potential of Atmanirbhar Bharat, Make in India, and the transformative vision of Viksit Bharat @2047.

READ I India faces Hobson’s choice as US slaps 50% levy

The Export Dependency Trap

Since the 1991 liberalisation, Indian policymakers have often looked eastward—towards South Korea, Taiwan, and China—for inspiration. The model seemed straightforward: undervalue the currency, incentivize low-cost manufacturing, and export to the West. Yet this model was never a natural fit for a continental-scale economy like India. With a population of 1.4 billion and a rising middle class, India’s most powerful market is internal, not external. Export dependency makes India vulnerable to political volatility in foreign capitals, as the 50% US tariff proves.

This moment must mark the end of the illusion that India’s future lies in chasing foreign markets. Instead, we must build an economy of, by, and for Indians—a model rooted in domestic investment, infrastructure, innovation, and inclusive growth.

The real source of money: Money creation through bank lending

A key question arises: how can India finance this national transformation without increasing taxes or begging for foreign capital?

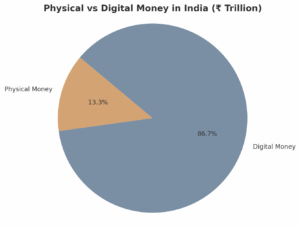

The answer lies in understanding the real mechanics of money creation. Contrary to popular belief, money in a modern economy is not primarily printed by the central bank RBI, nor is it borrowed from abroad. More than 90% of all money in modern economies like the USA, UK, Germany, China, Japan, Singapore, India and others is created when commercial banks make loans.

When a bank extends a loan—say, for a new home or a factory—it creates a new deposit in the borrower’s account, as the accounting entry. This is practically new money coming into existence, and not a redistribution of existing bank deposits, which is the general perception of how banks work. When the loan is repaid, that money created through the loan disappears. At any moment, new loans are being created, while old loans are getting repaid, and the balance remaining expands the money supply.

Instead of an endless debate, this process of money creation through bank lending can be easily validated by reviewing the accounting entries made when any type of bank loan is funded by any bank in India or anywhere in the modern world. This dynamic expansion and contraction of credit is the true source of money that fuels an economy, and the overall growth in a nations wealth.

But here’s the critical insight: not all money creation is equally beneficial.

When banks lend for new productive activity—like building a new house, starting a factory, or buying a new vehicle—it adds to the GDP (Gross Domestic Product), which is the total value of goods and services created in a country, in a given year.

When banks lend to purchase existing assets—like an old house, an old car, or speculative financial instruments—it does not directly add to GDP, but it merely inflates existing asset prices. This distinction—productive vs. non-productive money creation—is at the heart of intelligent economic policy. And it’s where India has a transformative opportunity.

How to guide credit: Differentiate by purpose, not just borrower

India must now implement differentiated interest rate regimes to guide money toward its most productive uses.

Loans for productive investments—such as new infrastructure, green energy, manufacturing, housing, or transport—should be offered at very low interest rates (1–2%).

Loans for non-productive purposes—like speculative real estate purchases, resale of existing assets, or financial asset trading—should carry higher interest rates (8–10%).

This is not theoretical. It echoes Japan’s “window guidance” strategy in the 1950s and 60s, which directed bank credit into steel, autos, housing appliances and electronics—laying the foundation for its post-war boom. China has now used similar tactics to build entire cities, rail networks, and tech hubs.

Interest rates practically are the ‘rental cost’ when one borrows new money created through a loan. Lowering the rental cost of new money when it results in a net addition to GDP encourages and contributes to GDP growth, so this type of money creation should have lower interest rates. But new money created to purchase existing assets, that do not result in a net contribution to GDP, should be made expensive through higher interest rates.

India has already launched many strategic missions that need this kind of financing support:

- Make in India for manufacturing self-reliance

- PLI Scheme for electronics, batteries, solar, and high tech manufacturing.

- PM Awas Yojana for housing for all

- Gati Shakti and the National Infrastructure Pipeline to modernize logistics

- Viksit Bharat 2047 as a national vision for full-spectrum development

These programs don’t just need policy support. They need capital—and the Indian banking system has the ability to generate it.

A financial system that matches national ambition

Let’s dig deeper by looking at comparative financial figures:

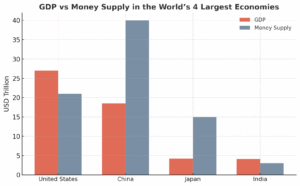

The United States has a total money supply exceeding $21 trillion dollars today, mostly created and supported by nearly 10,000 banks and credit unions, which are not-for-profit banks.

China has over 4,000 banks, having grown from just 4 banks in the 1980’s, with total credit creation exceeding $40 trillion in US dollar terms, which is almost double that of the USA’s total money supply. This is practically visible through China flexing it’s economic muscle all over the world today.

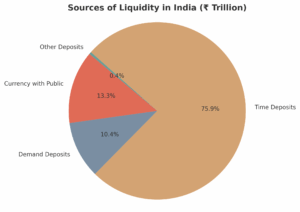

India, in stark contrast, has just 33 Indian scheduled commercial banks conducting over 90% of the country’s banking business today, and a total money supply in dollar terms of just around $3 Trillion.

This is a dangerously narrow financial base for a $ 4 trillion plus Indian economy and GDP. Expanding the money supply through increasing the number of banks —alongside strategic window guidance for productive credit creation—is critical to democratizing credit and unleashing India’s entrepreneurial energies.

But what about inflation?

The conventional fear is that too much money creation will cause inflation, which is the rise in prices of essential items, tracked by the CPI (Consumer Price Index). But history shows that India’s inflation spikes are typically caused by supply-side shocks, and not excess liquidity through expansion of the money supply, as this in fact only increases the demand and consumption of non-essential items.

- Food inflation follows bad monsoons or poor storage infrastructure

- Fuel inflation follows global oil crises

- Housing inflation follows restrictive regulations and limited supply

If new money is used for productive output, to increase supply, it is not inflationary—it is in fact disinflationary. For example:

- Loans for cold storages reduces food waste = lower food prices

- Loans for solar factories reduces oil imports = stable energy costs

- Loans for affordable housing increases supply = lower rents

Loans for semiconductor fabs reduces import dependency = tech price stability

Inflation is not about how much money is created, but where it goes, and also the supply dependencies of essential items.

Viksit Bharat: Now or never

The government of India’s strategic initiatives have already laid the groundwork for development and national transformation:

- Atmanirbhar Bharat to localize production and reduce external dependency

- Make in India to reinvigorate domestic industry and productive output

- PM Awas Yojana to provide homes for all

- PLI Schemes to build high-tech capacity in electronics, batteries, and clean energy

- Gati Shakti and Bharatmala to revolutionize logistics and infrastructure

These are not slogans. They are blueprints. What’s needed now is the financial fuel—credit at scale, at low cost, directed with discipline towards increasing productive output for the country. India’s banks, with proper regulation and government window guidance, can create this money, provided it’s channeled into productive investment. And this, in turn, can make Viksit Bharat not just a dream, but a reality—a lot sooner than we imagine.

The real message of the 50% tariff

The White House may have hoped to weaken India with its tariffs. But in doing so, it may have liberated India from its final illusion—that prosperity lies in pleasing foreign consumers. India’s future lies in building a credit-powered domestic growth engine, aligned with its national goals.

We have the people, being the youngest and most populous country in the world, with an average age of 29, compared to the USA at 39, China at 40, Japan at 50, and Europe at 48. We have the skills. We have the institutions. And yes, we can ‘create’ the money we need to grow.

Let us use this moment not to retreat, but to accelerate—toward a sovereign, resilient, and globally respected India. This is not a crisis. This is the spark that can ignite the Indian Century!

For any individual or traditional ‘economist’ debating the points expressed in this article, please review the data available publicly, or just ask ChatGPT or Gemini about ‘who creates money in the modern economy, and what percentage of this money created is by central banks versus commercial private banks’.

Vinod Tharakan is Chairman, CUNextGen, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA, and managing director, ClaySys, Kochi, India.