India’s urban governance continues to grapple with the corrosive influence of middlemen. From real estate dealings to welfare schemes such as MGNREGA, intermediaries often distort public systems for private gain. Even in relatively advanced city administrations like Bengaluru’s BBMP, citizens are forced to depend on layers of informal networks and clientelism to access basic services. This undermines the promise of Viksit Bharat, which envisions technology-driven, citizen-centric governance.

Digitisation offers a path to reduce these distortions. The National Urban Digital Mission (NUDM), launched by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, is a timely intervention. It aims to provide governance services on demand while empowering citizens through digital infrastructure. As digital platforms mature and penetrate deeper into urban life, the traditional role of intermediaries and patronage politics is being challenged. This article explores how e-governance—backed by emerging technologies like AI—can help eliminate middlemen, level the playing field, and restore equity in urban service delivery.

READ | Trade deficit falls, but crude price risk persists

Evidence from smart cities

India’s urban governance has historically been shaped by unequal citizen representation and informal power structures. Studies have shown how access to municipal services often depends more on one’s social capital than on legal entitlements. Marginalised communities face bureaucratic delays, while the middle class leverages RWAs or personal networks to fast-track service delivery. The result is a fragmented, inequitable system that weakens accountability and fuels corruption.

A shift, however, is underway. According to a December 2024 report by IIM Bengaluru, the Smart City Mission has enabled mobile-based platforms—such as the Smart City Mission Application (SCMA)—that allow citizens to raise grievances, apply for water and sewage connections, building permits, and access other civic services. These applications also enable payment of property taxes, electricity bills, and solid waste fees directly, bypassing middlemen and brokers.

Grievance redressal in urban governance

The grievance redressal feature is particularly transformative. Traditionally, citizens would rely on local councillors or MLAs to escalate their complaints—an arrangement fraught with political gatekeeping. Now, with mobile apps providing direct, trackable channels, this dependency is being reduced. Citizens from all socio-economic backgrounds—regardless of their proximity to power centres—can lodge complaints, receive updates, and hold local bodies accountable.

While researchers like Smitha and Sridhar have documented the prevalence of direct interactions between citizens and elected officials, especially among middle-class populations, the digital route promises a more egalitarian and structured approach. Reducing the reliance on informal actors such as party workers, community clubs, or local fixers is essential to streamline urban service delivery and eliminate opportunities for rent-seeking.

From transactional to intelligent governance

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into mobile-based governance platforms marks the next phase of urban digitisation. AI-enabled applications can simplify interfaces, guide users through complex procedures, and even auto-fill forms or resolve common queries. This is particularly relevant in bridging the digital divide for older citizens or those unfamiliar with navigating bureaucratic websites.

Moreover, AI tools can analyse complaint patterns, prioritise urgent civic issues, and evaluate the performance of municipal bodies based on resolution timelines. These features not only enhance transparency but also create a feedback loop that drives systemic improvements. For example, AI-driven insights could inform ward-level planning, allowing governments to allocate resources more efficiently and address service gaps before they escalate.

The ripple effects are wide-ranging. Citizens empowered with data and real-time tracking may also be more inclined to participate in sustainability initiatives—such as composting, water conservation, or community waste management—making governance participatory rather than top-down.

Still, the full promise of such tools remains distant for many. Awareness and usability gaps persist. In smaller cities and towns, digital literacy levels are low, and access to smartphones and the internet remains uneven. These limitations underscore the need for human support systems and community outreach to complement technology rollouts.

Between vision and ground realities

While digital governance holds enormous potential, its widespread adoption faces structural challenges. Many city-specific mobile apps offer only limited functionalities and are underutilised due to poor user awareness. A large share of urban residents—especially in tier-2 and tier-3 towns—still depend on physical interactions with municipal staff or intermediaries to get work done.

At the National Urban Conclave 1.0, Dr Debolina Kundu, Director at the National Institute of Urban Affairs, highlighted these constraints. Citing the example of the UPYOG platform, she noted how digital systems must be designed to be open, reliable, and inclusive. While platforms have improved service delivery in larger cities, scaling them to smaller urban centres with fragile technical capacities remains a major hurdle.

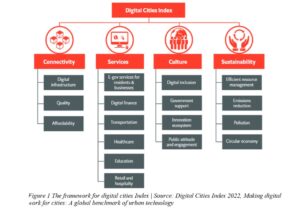

The framework for digital cities, as envisioned under NUDM, rests on four pillars: enhanced connectivity, ease of service delivery, improved quality of life, and citizen participation. But realising this framework requires more than just apps and dashboards. It calls for digital literacy campaigns, robust internet access, and political will to dismantle entrenched patronage networks.

Current rankings under the Digital City Index show that most Indian cities are still far from optimising their digital potential. A focused reform push—combining policy, infrastructure, and public engagement—is critical to bridge this gap.

If India is to achieve the ambitions of Viksit Bharat@2047, urban governance must be freed from the grip of intermediaries and opaque systems. Digital platforms, when thoughtfully designed and equitably deployed, can democratise access to services, reduce corruption, and restore citizen trust. But for this vision to translate into everyday reality, cities must invest not just in technology, but also in people—training them, informing them, and including them in the governance process. Only then can the middleman truly be taken out of the equation.

Riya Bhattacharya is a Senior Research Fellow, Institute of Social and Economic Change, Bengaluru.