In 2025 the Republic of Korea will host the celebrations in Jeju under the banner ‘Beat Plastic Pollution’, just two months before governments reconvene in Geneva for what is meant to be the final round of talks on a legally binding plastics treaty.

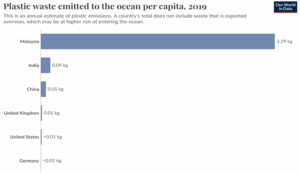

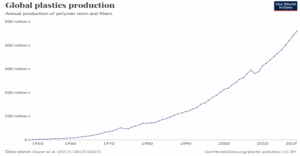

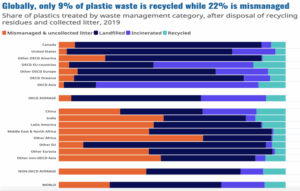

Plastic output has rocketed from 2 million tonnes in the 1950s to about 460 million tonnes today and, without hard policy brakes, could almost triple by 2060. Barely a fifth is ever recycled; the rest is burned, buried or sweeps into rivers and seas. Some 5 million tonnes of scrap plastic moved across borders in 2020, often to places that cannot handle it safely, magnifying the environmental toll.

READ I Ukraine’s drone attack on Russia redefines global deterrence

The plastics treaty imperative

Once adrift, packaging shreds into micro- and nanoplastics that have now been detected in human liver, kidney and even brain tissue, while the OECD puts full life-cycle emissions from plastics at 1.8 billion t CO₂-equivalent a year—roughly the output of Russia—undermining every other climate-

Two negotiating sessions—INC-4 in Ottawa and INC-5.1 in Busan—broke up last year without consensus on production caps or a chemical phase-out list. Delegates meet again in Geneva (5–14 August 2025) with a slimmed-down “chair’s text,” but the article that would throttle virgin polymer output remains bracketed and bitterly contested. Business, too, is split: a coalition of 250-plus firms has endorsed the “Bridge to Busan” declaration calling for mandatory global limits, while petro-chemical producers lobby for voluntary targets.

Waiting for Geneva is not an option. India’s live EPR portal is mapping packaging flows in real time but still leaves informal recyclers to do the heaviest lifting. The European Union’s proposed Packaging and Packaging-Waste Regulation will make every pack on the single market recyclable by 2030, and California’s recycled-content law already forces beverage makers to meet a 25 per cent threshold next year—proof that aggressive timelines are possible.

Designing for a circular future

More than 250 companies—including IKEA, Unilever and Walmart—have signed the Bridge to Busan declaration urging negotiators to agree on “sustainable levels of production of primary plastic polymers” and eliminate the tax hand-outs that keep virgin resin artificially cheap. Their warning is stark: without a binding cap, polymer output could triple by mid-century, wiping out downstream gains and locking in fresh demand for fossil feedstock. The chair’s draft on the Geneva table still contains that option, but petro-state resistance has not softened.

Durability and modular repair have to become the default, not the niche. The EU’s forthcoming PPWR would compel manufacturers to ensure all packaging is reusable or recyclable by 2030 and reward refill systems. In the United States, California’s Assembly Bill 793 ratchets recycled-content requirements to 25 per cent in 2025 and 50 per cent in 2030, instantly creating a premium market for high-quality scrap plastic that ripples through global supply chains.

Algae-based polymers, once a laboratory novelty, are inching towards commercial scale. Start-up Sway will begin selling compostable seaweed poly-bags through EcoEnclose this year, and analysts already size the algae-bioplastics market at more than USD 100 million, growing at 5 per cent annually. Venture capital is pouring into mycelium foams, coffee-waste wraps and other fossil-free substitutes, especially in Europe and India, where retailers scramble to future-proof supply chains.

Finance where leakage is worst

The OECD says USD 2.1 trillion will be needed between 2025 and 2040 to build the waste-management systems that the Global South lacks. The World Bank’s Plastic Waste Reduction-Linked Bond—a $100 million issue that ties investor returns to verified collection credits in Indonesia and Ghana—shows how blended finance can work, but such deals remain flea-sized next to the mountain of need. Treaty negotiators are weighing a dedicated fund, akin to the Green Climate Fund; without it, poorer nations will struggle to implement even the most modest obligations.

Plastic propelled a century of ingenuity; unmanaged, it could underwrite a century of degradation. On this World Environment Day, governments have a narrowing window to align national reforms with a treaty that tackles polymers from the well-head to the waste-bin. If they miss, the most durable quality of plastic will prove to be its capacity to outlast political hesitation—and perhaps the resilience of the planet itself.

Dr Md Mashhood Alam is an independent Climate Change Analyst and Social Worker currently associated with PACE Creative British School in Ajman, UAE.