Importance of India-EU FTA: Trump’s tariff shock has hardened trade blocs, pushed firms to “friend-shore”, and made market access a political weapon. India’s renewed push to conclude a Free Trade Agreement with the European Union is best read in that context. This is not a routine tariff bargain. It is India’s attempt to rebalance external economic exposure towards a large, rules-driven market at a time when the United States and China come with rising political and strategic risk.

India’s export performance across the EU, the US and China since 2013 tells a simple story. The US surge after 2020 is real, but it is also the most exposed to domestic politics and unilateral trade action. China is a major trading partner, but India’s dependence is asymmetric and strategically fraught. The EU looks less dramatic, but more dependable.

Exports to the EU rose on a steady path from roughly $45.7 billion in 2013 to over $77 billion in 2024, even though periods of global stress. Exports to China were volatile. Trade balances also diverged sharply. India’s deficit with China widened from about $35 billion in 2013 to more than $112 billion by 2024. With the US, India’s surplus has grown, but remains vulnerable to policy shifts. With the EU, India’s trade balance improved from around $2.8 billion in 2013 to nearly $29.2 billion in 2024, with less volatility than either the US or China.

That is why the EU is not just “another market”. It is a stabiliser in a portfolio that is otherwise overexposed to politics.

READ I India-EU trade deal: CBAM compliance becomes competitiveness

What India sells, what Europe sells

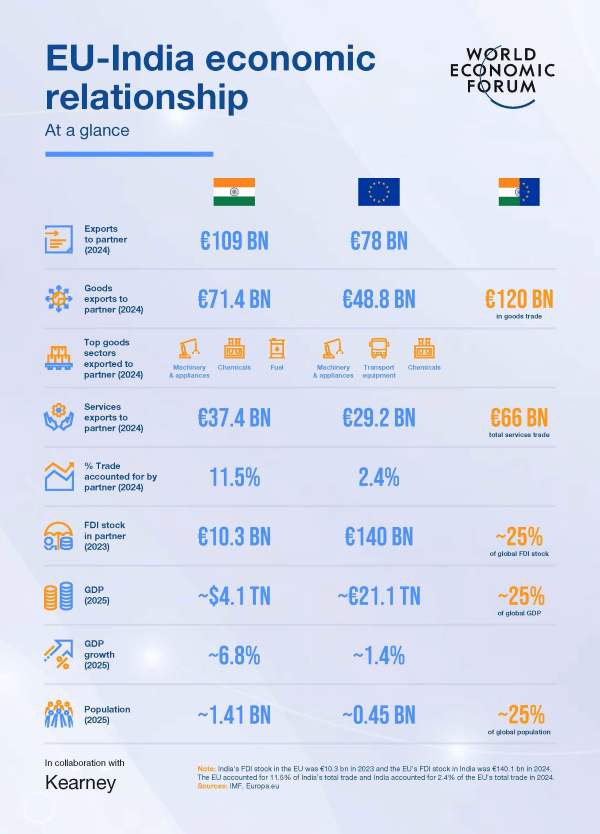

India’s exports to Europe are concentrated in machinery, electrical equipment, chemicals, textiles, and gems and jewellery. EU exports to India skew towards high-technology machinery, transport equipment, pharmaceuticals, and other capital goods. That composition matters for negotiations.

For India, the near-term prize is improved market access for goods and services. The longer-term prize is deeper insertion into European value chains, especially in advanced manufacturing, clean technologies and high-spec engineering where Europe sets global benchmarks.

READ I India-EU trade is set to grow; its environmental costs may grow faster

India-EU FTA and non-tariff barriers

The hardest barriers for Indian exporters are not tariffs. They are European standards and compliance regimes covering environment, labour and product safety. Indian firms also remain thinly integrated into European value chains. Without workable rules of origin, mutual recognition arrangements, and serious regulatory cooperation, Indian suppliers compete at a structural disadvantage.

A credible FTA has to be designed for that reality. If it merely shifts some exports from the US to the EU, it will underdeliver. The point is to reduce the “compliance premium” Indian firms pay and to convert European standards from a barrier into a discipline that lifts competitiveness.

READ I What India-EU FTA means for exports, industry and services

Digital trade, services and procurement

What distinguishes the India–EU FTA talks is scope. This negotiation is not limited to tariff lines. It covers digital trade, services, investment protection, intellectual property, sustainability, and government procurement. That breadth is exactly why it matters.

India cannot treat these chapters as add-ons. For Indian IT and professional services, clarity on cross-border data flows, recognition of qualifications, and predictable regulatory pathways can be as valuable as tariff cuts for manufacturers. Procurement disciplines can open opportunity, but they also demand domestic capacity to compete on quality, timelines and compliance.

Carbon rules: Resist, or upgrade

The EU’s carbon border measures and due-diligence requirements worry Indian exporters. Some of that anxiety is justified. Compliance costs are real. Smaller firms will struggle first.

But a posture of outright resistance is short-sighted. If European markets are going to insist on lower carbon intensity and traceable supply chains, India has a choice. It can treat this as a permanent grievance, or use the India-EU FTA to access European technology, finance and management practices that help Indian industry upgrade. In time, these “conditionalities” may matter less as barriers and more as entry tickets to higher-value markets.

Agri-processing liberalisation

One notable element in the negotiation logic is the focus on value-added agriculture rather than raw commodity liberalisation. High tariffs on processed foods have long constrained branded agri-trade. Tariff reductions on processed foods, alongside steep cuts on items such as wine and olive oil, indicate a shift towards agri-processing and branded trade.

At the same time, excluding sensitive farm products can prevent liberalisation from becoming a political flashpoint. The balance India should seek is simple: expand trade where productivity gains are plausible, and protect lines where asymmetries in subsidies, scale and market power are too stark.

Germany and the missing Europe problem

Within the EU, India’s trade is concentrated. Germany accounts for a large share of exports, especially in machinery, automobiles and industrial inputs. Yet India’s exports to Germany have grown more slowly than imports, reinforcing the bilateral imbalance.

A well-structured FTA can unlock sector-specific gains with Germany, France, Italy and the Netherlands. Lower tariffs on automobiles and components will help, but the bigger opportunity lies in joint ventures, technology transfer, and supplier development that allow India to serve Europe as a manufacturing and engineering base rather than as a marginal vendor.

Trade diversion is already built into EU policy

India also faces a competitive clock. The EU has concluded or upgraded agreements with Vietnam, South Korea, Canada and Japan. Preferential access for these partners erodes India’s competitiveness in precisely the sectors where India wants to scale. EU import demand may grow, but India’s share will not automatically follow. In a world of overlapping FTAs, staying out is not neutrality. It is a choice that hands advantage to competitors.

Critics frame FTAs as threats to domestic industry. That fear is often overstated, but it cannot be dismissed. India’s recent agreements with the UAE, Australia and EFTA show a more pragmatic template: selective liberalisation, phased tariff reductions, safeguards, and clear focus on export-ready sectors. India should apply the same discipline here. The aim is not “openness” as virtue. The aim is strategic integration on terms India can absorb.

The US “softening” is not a reason to relax

Renewed momentum on the India-EU FTA coincides with what looks like a softer US trade posture towards India. This should not be taken at face value. It could be tactical, aimed at extracting deeper access to India’s agricultural markets, among the last heavily protected sectors. Any such opening would have distributional consequences for Indian farmers given asymmetries in subsidies, scale, and buyer power. India should negotiate with the EU on its own merits, not as a by-product of Washington’s mood.

The EU is too large to ignore, too structured to approach casually, and too consequential to postpone. If concluded well, the India-EU FTA can move India from being a peripheral supplier to a more embedded participant in European supply chains.

Process will take time. Draft text, legal scrubbing, translation, approval by the EU Council and European Parliament, and ratification on both sides will still follow. But the strategic question is immediate. It is not whether India should sign an FTA with the EU. It is whether India can afford delay in a world where market access is increasingly pre-assigned through rival FTAs.

Dr Jadhav Chakradhar is Assistant Professor of Economics at the Centre for Economic and Social Studies (CESS), Hyderabad, Telangana, India.