India’s edible oil sector exemplifies a policy paradox. Despite being the fourth-largest producer of oilseeds globally, the country imports nearly 60% of its edible oil needs. The annual import bill — exceeding $15 billion — not only deepens the trade deficit but also highlights the vulnerability of India’s food system to global supply shocks.

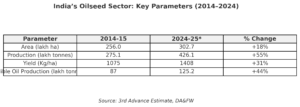

Oilseed production has grown significantly over the past decade. Between 2014-15 and 2024-25, output rose by 55%, thanks to an 18% increase in acreage and a 31% improvement in yield. Government schemes like the National Mission on Edible Oils – Oil Palm and Oil Seeds laid the foundation for progress. Yet, these gains have been offset by even faster growth in demand.

READ I Rate cuts make sense — but only if banks pass them on

Growing demand, stagnant self-reliance

India’s edible oil consumption touched 27.8 million tonnes in 2023-24—up sharply from a decade ago. Per capita consumption now stands at 19.3 kg annually and is projected by NITI Aayog to rise to 25.3 kg by 2028. This is driven by rising incomes, urbanisation, dietary shifts toward processed foods, and the proliferation of hotels and restaurants.

Such growth, while economically symptomatic of prosperity, has deepened reliance on imported palm, soybean, and sunflower oils—now exceeding 16 million tonnes annually. The result: substantial foreign exchange outflows that could otherwise fund infrastructure or rural development.

Caught in the cobweb

Oilseed cultivation suffers from classic boom-bust cycles—akin to what economists term the Cobweb Model. A price surge, as seen during the 2021 soybean boom, encourages expanded planting. But global adjustments soon follow, depressing prices. With limited procurement and no functioning market-based risk hedging, farmers are left to sell at a loss.

The Minimum Support Price (MSP) remains mostly nominal. Unlike rice and wheat, where procurement is institutionalised, oilseeds rarely see systematic support. Crops like mustard and groundnut have experienced similar cycles, leaving growers disillusioned and further away from the goal of self-sufficiency.

The irrigation dilemma

Oilseeds are naturally suited to rainfed agriculture. Yet, as irrigation networks expand, farmers shift to water-intensive and better-supported crops like paddy and sugarcane. These offer better price realisation and procurement security. The result is oilseeds being relegated to marginal lands with lower productivity and inadequate institutional support.

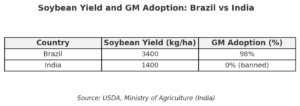

This structural disadvantage ensures India’s average oilseed yield remains at 1,408 kg per hectare—less than half that of countries like the U.S. and Brazil, which average over 3,200 kg. The technology gap is a key factor, especially the absence of genetically modified (GM) seeds that dominate global production. Brazil, for example, uses GM varieties on 98% of its soybean acreage.

India’s moratorium on GM food crops has stifled yield potential. A cautious, evidence-based rethink is overdue, especially if productivity is to catch up with global benchmarks.

An uneven policy playing field

The policy framework remains conflicted. On the one hand, low import duties help contain food inflation and serve consumer interests. On the other, cheap imports depress domestic prices, hurt farm incomes, and stymie investment in local processing and value chains.

This balancing act—between protecting the consumer and securing farmer livelihoods—has weakened incentives for growing oilseeds and developing domestic processing clusters.

A systems-based strategy

India’s edible oil challenge cannot be solved through piecemeal interventions. What is needed is a coordinated, systems-based approach that combines productivity gains, institutional reform, infrastructure investment, and consumer engagement. Six key focus areas emerge.

Seeding the next generation

Quality seed is the first lever of productivity. India must accelerate the development and dissemination of high-yielding, climate-resilient, pest-resistant oilseed varieties. The National Mission on Edible Oils has rightly emphasised long-term seed planning. Budget 2025 proposes a new mission focused on high-yielding seeds across crops, with R\&D for oilseeds and pulses a priority.

To be effective, this effort must overcome structural gaps in India’s seed innovation ecosystem. Public-private partnerships, faster regulatory clearances, and international collaborations in gene-editing are essential.

Reforming price and procurement

MSP without procurement is symbolism. A functioning Price Deficiency Payment Scheme (PDPS), already piloted in states like Madhya Pradesh, could provide income assurance without creating stockpiles. Integrating procurement platforms with digital infrastructure—such as AgriStack and e-NAM—can improve transparency and build farmer trust.

Recent successful pilots by NAFED and NCCF in digital procurement show that scalable models exist, but require stronger institutional push.

Cropping smarter

Policy must reward sustainability. Oilseeds use less water, enrich soil, and offer better carbon efficiency. Linking schemes like PM-Kisan to crop choice, redirecting subsidies, and integrating carbon markets could make oilseeds more competitive, especially in ecologically stressed regions.

This would encourage farmers to view oilseeds not as fallback options, but as profitable and climate-aligned choices.

Strengthening the value chain

Self-reliance in edible oils requires more than farm-level interventions. Processing infrastructure—solvent plants, oil mills, protein extractors—must expand in oilseed-rich belts. Fiscal incentives, easier credit, and FPO-led models can build regional value chains.

Secondary oil sources such as cottonseed and rice bran remain underutilised. India produces over 1.2 million tonnes of rice bran oil annually—a healthy and sustainable alternative that deserves policy attention.

Value addition must extend from seed to shelf, emulating models seen in Brazil and the U.S., where vertically integrated systems ensure efficiency, scale, and farmer profitability.

Reducing post-harvest losses

Oilseeds are susceptible to post-harvest damage. Aflatoxin in groundnut and soybean, exacerbated by poor storage and moisture stress, results in high losses.

Modern storage infrastructure—especially moisture-controlled facilities in production zones—must be prioritised. This would help farmers avoid distress sales and allow better market timing. A robust commodity futures market for oilseeds and oils, once revived, can offer price signals and hedging tools to reduce risk.

Influencing consumption

Supply-side interventions must be complemented by behavioural change. Domestic oils like mustard, sesame, and rice bran need branding, labelling, and nutrition advocacy. Tamil Nadu’s successful campaign promoting cold-pressed sesame oil—backed by FPOs and NGOs—saw local demand rise by 20% in a year.

The Prime Minister’s call to reduce oil consumption by 10% is a welcome nudge. A national campaign, tied to health messaging and self-reliance goals, can reshape demand and reduce the pull of cheap imports.

Dynamic tariffs and trade vigilance

India needs a smarter tariff policy. During global price slumps, higher import duties can shield farmers. When prices spike, temporary duty cuts can protect consumers.

Such flexibility demands institutionalised, data-driven mechanisms. Revenues from high-duty phases must be reinvested into farm support, R\&D, and infrastructure.

Equally important is reviewing FTAs that allow duty-free oil inflows from countries that are not original producers. Loopholes that undercut domestic interests must be plugged if self-reliance is to be achieved.

Reclaiming control of the oil bowl

India’s edible oil story is one of both potential and vulnerability. A fragmented approach has delivered incremental gains, but not strategic transformation.

What is required now is coherence—between technology, pricing, trade, infrastructure, and consumer behaviour. A diversified oilseed basket, stronger processing backbones, empowered FPOs, and smarter demand must together form the new framework.

Until that happens, India’s oil bowl will continue to depend on foreign shores—an economic and strategic liability that the country can no longer afford.

Ajeet Kumar Sahu is Joint Secretary and Rishi Kant is Additional Economic Adviser in the Department of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare. The views are personal.