Why does an Indian student of public finance know more about Adam Smith’s invisible hand than Kautilya’s philosophy of taxation, which likens statecraft to the art of a bee collecting honey—gently, without hurting the flower? Why are Musgrave and Keynes taught in every economics classroom, while ancient Indian treatises like the Arthashastra remain conspicuously absent?

These questions go to the heart of a deeper malaise. India’s public finance education, while firmly grounded in modern global theory, has failed to engage with its own intellectual heritage. In doing so, it perpetuates an incomplete and chronologically inconsistent understanding of economic thought.

READ | From poverty to precarity: India’s uneven growth story

A tilted pedagogy

Public finance—concerned with taxation, public expenditure, budgeting, and debt—forms the backbone of state governance. It is not merely about collecting revenues but about distributing them equitably to foster stability, growth, and justice. Yet in India, this subject is still taught almost exclusively through a Western lens. Canonical figures like Adam Smith, with his four canons of taxation—equity, certainty, convenience, and economy—are standard fare. But few students are taught that similar principles were articulated by Kautilya over two millennia ago.

This curricular skew is not just a relic of colonial influence. It reflects a deeper epistemological gap—an unwillingness to treat indigenous knowledge systems as intellectual equals. The result is a pedagogy that sidelines India’s own contributions to economic and fiscal theory, reducing them to historical curiosities rather than living frameworks.

A rich tradition of public finance

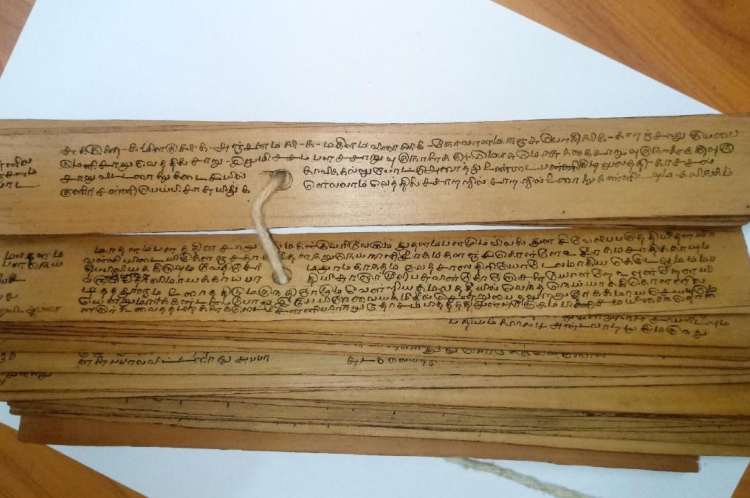

Kautilya’s Arthashastra, written in the 3rd century BCE, remains one of the most comprehensive ancient treatises on statecraft and economic governance. At its core lies the assertion: “From the treasury comes the power of the government.” Kautilya outlines tax systems that are equitable, predictable, and designed to avoid burdening the taxpayer. His prescriptions for land taxes, trade duties, and occupational levies are grounded in administrative cost, economic utility, and social equity.

The Manusmriti, composed between 200 BCE and 200 CE, brings a normative dimension to this discussion. It prescribes tax rates—one-sixth of agricultural produce, one-fiftieth of gold, one-twelfth of trade profits—tailored to a citizen’s capacity and occupation. Despite its embeddedness in a hierarchical social order, Manu’s insistence on proportional and non-arbitrary taxation echoes the logic of modern progressive tax systems.

Thiruvalluvar’s Thirukkural, a moral treatise from the 1st century BCE, frames governance in ethical terms. While not a fiscal manual, its teachings on justice, equity, and the responsibilities of rulers implicitly critique extractive governance. It demands that statecraft serve the people, not exploit them.

These texts form a triadic foundation: Kautilya provides the administrative blueprint, Manu sets ethical boundaries, and Thiruvalluvar offers philosophical purpose. Together, they construct a robust, culturally rooted framework for public finance—yet one that modern curricula largely ignore.

Global parallels, missed opportunities

Ancient India was not alone in grappling with public finance. China’s Guanzi (7th century BCE) discusses price controls and state intervention to ensure economic stability—an early articulation of Keynesian logic. Rome, with its twin treasuries—the aerarium and fiscus—designed tax systems to fund infrastructure and the military, not unlike today’s fiscal frameworks.

Despite these global traditions, India’s educational institutions remain bound to Western theorists. Musgrave’s three functions of public finance—allocation, distribution, stabilisation—are widely taught. Yet Kautilya’s tripartite resource allocation—for the sovereign, public goods, and disaster relief—receives scant attention, even though it predates Musgrave by centuries and mirrors his ideas in substance.

Decolonising the fiscal canon

Critics may argue that these ancient texts are context-specific, rooted in monarchies and caste-based societies, and hence unsuited to democratic modernity. But this line of reasoning risks throwing out ethical and pragmatic principles with the bathwater of historical specificity. The core tenets of just taxation, accountable governance, and welfare-driven policy are not exclusive to any time or system—they are universal.

A comparative, pluralistic approach to public finance would enrich Indian classrooms. It would allow students to analyse multiple frameworks, identify resonances and tensions, and form more grounded judgments about fiscal policies. This is not about cultural revivalism or nationalist tokenism. It is about intellectual integrity—and about decolonising knowledge without discarding rigor.

A curriculum for the future

India can continue importing economic frameworks wholesale, or it can draw from its own traditions to complement global thought. Integrating ancient Indian economic philosophy into mainstream economics curricula is not about replacing Musgrave with Kautilya or Adam Smith with Thiruvalluvar. It is about placing them side by side and inviting students to compare, contrast, and learn.

This rebalancing is long overdue. Ignoring indigenous traditions fosters a lopsided education that distorts the lineage of economic thought and constrains innovation to Eurocentric paradigms. India—with its deep repository of fiscal wisdom—is uniquely placed to lead this intellectual transformation.

Such a shift would not just correct a historical oversight. It would enrich public discourse, nurture critical thinking, and prepare a generation of economists and policymakers attuned not only to global models but also to local realities and ethical imperatives.

Reclaiming this legacy is not a nostalgic retreat into the past. It is a leap toward a more inclusive, reflective, and resilient economic education. That, too, is a public investment worth making.

Debdulal Thakur is Professor, Vinayaka Mission’s School of Economics and Public Policy, Chennai. Shrabani Mukherjee is Associate Professor, Department of Economics, Shiv Nadar University, Chennai. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position, or endorsement of any institution they are affiliated with.

Debdulal Thakur is Professor, Vinayaka Mission’s School of Economics and Public Policy, Chennai.