The 2023 G20 India summit underscored the significance of digital technology, illustrating how India could be a pioneer in this domain. A particular emphasis was placed on the role of digital technology in promoting financial inclusion. However, introducing technology to the broader population demands specific measures. In this context, the impact of common services centres, which evolved under the Digital India programme, is noteworthy.

Today, most government schemes need online enrolment. This process, which involves tasks such as uploading documents, can be daunting for the average citizen. The common services centres, operated by certified village-level entrepreneurs (VLEs), bridge this gap. They set up outlets to facilitate these online registrations and applications, and assist with government ID registrations for a nominal fee.

READ I Beyond price tags: India’s food inflation crisis explained

Common services centres and digital governance

These centres democratise e-government services for those without digital literacy or internet access. Notably, they further financial inclusion by enabling VLEs to provide banking services like balance checks, deposits, and even crop insurance in rural locales. As of May 2023, over 5 lakh CSCs are operational across India (source: csc.gov.in). The digital foundation of these centres empowers women to undertake micro-entrepreneurship from home, navigating socio-cultural barriers, and ensuring a decent income along with various social advantages.

The prominence of these centres is particularly heartening, given the low and decreasing labour force participation of women in India. Data from CMIE reveals that, as of April 2022, 31% of Indian women aged 25-29 were unemployed, in stark contrast to only 11% of their male counterparts. Thus, offering profitable employment opportunities to women remains paramount, just as it is essential to leverage digital technologies for the common good. By facilitating self-employment and optimising digital platforms to amplify the reach of government services, CSCs present considerable potential.

Research in Karnataka, undertaken by the author for Azim Premji University, disclosed that the average income of female CSC entrepreneurs was Rs 18,500—a figure marginally exceeding that of their male counterparts. Furthermore, three-quarters reported that initiating their CSC enterprise expanded their social networks. This increased social interaction often leads to enhanced decision-making power for these women, both domestically and within their communities, thereby significantly enhancing their well-being.

Yet, fully realising this programme’s potential is impeded by challenges. Intense competition among CSCs jeopardises their long-term viability. Additionally, some resort to unscrupulous means to augment their revenues. Consequently, a few state governments such as Karnataka’s have annulled CSC licences for citizen registrations, impacting both CSC revenue and the public’s access to services. Proper oversight might mitigate these malpractices, ensuring the effective distribution of government welfare. The absence of a grievance redressal mechanism hampers entrepreneurs from notifying officials about performance-inhibiting issues. Kerala, however, stands out with its well-monitored Akshaya Kendras.

Starting a CSC requires a significant investment, averaging around Rs 1.2 lakh for essential equipment. Most survey respondents financed this personally, indicating potential barriers for those without savings or access to credit. Despite government financial inclusion efforts, such as the Jan Dhan Yojana and MUDRA Yojana, credit access remains elusive and requires attention.

Digital literacy is another concern for women. Many, despite owning a CSC, depend on male family members for operations, curtailing their independence. Training programmes focused on equipping women with digital skills could significantly boost their entrepreneurial prospects and empowerment in this digital era.

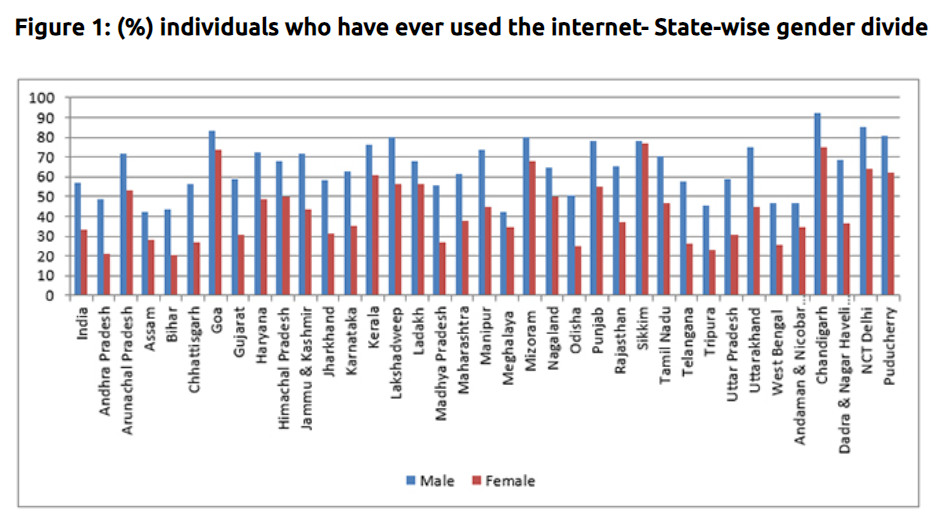

India, with its vast population and diverse socio-economic landscape, faces a pronounced digital divide. While urban centres and the younger generation have largely embraced the digital revolution, vast swathes of rural India remain disconnected or only partially connected. This digital chasm is influenced by factors such as limited infrastructure, financial constraints, and lack of digital literacy.

The disparity manifests not just in terms of access to internet-enabled devices but also in the quality of internet services available. High-speed connections, which urbanites take for granted, are often a luxury in many remote areas. Moreover, the content predominantly available in English poses an additional barrier for non-English speakers. This inequity in digital access has significant implications, particularly in the realms of education, healthcare, and economic opportunities, wherein the digitally disadvantaged find themselves at a distinct disadvantage.

To bridge this digital divide, it is imperative for both the government and the private sector to collaborate. Initiatives like the Digital India programme have made commendable strides, but the journey is far from complete. The focus should not only be on infrastructure development but also on fostering digital literacy across all age groups and demographics.

Tailored content in regional languages can make the digital world more inclusive. Additionally, innovations that consider the unique challenges of India’s vast rural landscape, such as low-cost devices and offline content solutions, can further narrow the divide. As India aspires to be a global digital leader, ensuring equitable digital access for all its citizens becomes not just a social obligation but a necessity for holistic national progress.

(Meenakshi Rajeev is RBI Chair Professor, Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore)