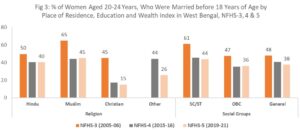

West Bengal presents a troubling paradox. The state performs reasonably well on several gender-development indicators, including girls’ school enrolment and maternal health. Yet it continues to record one of the highest rates of child marriage in India, particularly in rural districts. According to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5, 2019–21), about 42% of women aged 20–24 were married before the age of 18, rising to 48% in rural areas. More recent Sample Registration System (SRS) 2025 estimates reaffirm West Bengal’s position at the top of the national rankings.

This persistence makes clear that child marriage is no longer explained by poverty or ignorance alone. It is sustained by a dense interaction of educational deficits, social norms, risk perceptions, and local vulnerabilities. Economic progress and legal prohibition, by themselves, have proved inadequate.

READ | Distress migration: Anti-trafficking policy must focus on mental health

Education, not income, is the strongest shield

NFHS-5 data point to a consistent and powerful conclusion: education is the most effective deterrent to child marriage. Girls who complete secondary education—and especially those who progress to higher secondary or college—are far less likely to be married before 18. This relationship holds across income groups and geographies.

The decline in child marriage begins earlier in urban areas, where secondary education already has a protective effect. In rural Bengal, however, the impact becomes visible only when girls cross higher educational thresholds. The implication is stark. Without sustained schooling, even modest social progress fails to delay marriage.

Why household wealth offers limited protection

Household income plays a weaker and more uneven role. In urban areas, girls from wealthier households are indeed less likely to be married early. But in rural West Bengal, child marriage remains prevalent even among higher wealth quintiles. NFHS-5 shows that income alone does not offset entrenched norms when girls are out of school.

The contrast is revealing. Poor but educated girls face a lower risk of early marriage than wealthier girls with limited schooling. This establishes education—not income—as the decisive variable. Policies that rely primarily on cash transfers or general poverty reduction are therefore insufficient.

Social norms and parental anxiety

Field evidence from districts such as Malda helps explain why education matters so much. Interviews with parents and adolescents reveal a persistent belief that marriage is the primary life goal for girls. Delaying marriage beyond the mid-teens is often seen as reducing a girl’s “value” in the marriage market.

Parental anxiety plays a central role. Families fear elopement, premarital relationships, and social stigma. Early marriage is perceived as a form of protection and control rather than deprivation. In this context, legal prohibitions carry limited weight because the practice is socially validated.

Gendered schooling choices and early dropout

Education itself is shaped by gender bias. Many families prioritise schooling for sons while preparing daughters for domestic roles. Spending on girls’ education is often viewed as wasteful, especially when marriage is expected to follow soon after. Some parents also believe that educated girls become “less adjustable” or harder to marry.

These attitudes drive school dropout during adolescence—the very stage at which the risk of child marriage rises sharply. Once a girl leaves school, marriage often follows within months.

Contextual shocks reinforce early marriage

Local vulnerabilities intensify these pressures. Several high-prevalence districts face recurrent flooding, disrupting schooling and household incomes. Seasonal male migration adds another layer of insecurity. When adult men migrate for work, families perceive adolescent girls as more vulnerable, increasing pressure to arrange early marriages.

In such settings, child marriage becomes a coping strategy—a response to uncertainty rather than a relic of tradition alone.

Law exists, enforcement does not

India’s Prohibition of Child Marriage Act (2006) provides a clear legal framework. Yet enforcement remains weak, particularly in rural areas where marriages are often unregistered and conducted with tacit community consent. As with many social legislations, law collides with custom—and loses.

This underlines a crucial policy lesson. Legal deterrence cannot dismantle a practice that is normalised, locally sanctioned, and socially rewarded.

What policy must prioritise

A more effective response requires re-sequencing priorities. First, secondary and higher-secondary education for girls must be treated as a core social-infrastructure investment, not a welfare add-on. Schemes such as Kanyashree Prakalpa—which links financial incentives to continued schooling—have demonstrated potential, but need stronger targeting in high-risk districts.

Second, interventions must address local barriers. Flood-prone areas require schooling continuity plans. Unsafe travel routes demand transport and hostel solutions. Migration-affected households need community-level protection mechanisms.

Third, norm change must be local and sustained. Community engagement, parental counselling, and adolescent mentoring are essential complements to financial incentives. Without altering perceptions of girls’ agency and value, schooling gains will remain fragile.

West Bengal’s experience exposes a broader truth. Child marriage can persist even amid economic growth and progressive legislation. Ending it requires shifting the centre of policy from income support to education, social norms, and local resilience.

The objective is not merely to delay marriage. It is to expand choice. When girls stay in school, marriage ceases to be an inevitability and becomes a decision. That transition—quiet, structural, and deeply political—is the real measure of progress.

Pintu Paul is an Assistant Professor at the Indian Social Institute, New Delhi. Email: pintupaul383@gmail.com