Female labour force participation: In India, unpaid gendered burden of housework enabled by cultural norms functions as a trap which leaves women with limited opportunities to engage in the labour market or forces them into premature exit from work. Improved literacy and educational attainment among women in India are not accompanied by increased work participation. Apart from cultural norms and low availability of decent childcare facilities, labour market discrimination is also an important barrier.

This article draws on data from the Time Use Survey (TUS) 2019 and annual Periodic Labour Force Survey 2019-20 (PLFS) to highlight high participation in unpaid housework and low work participation among women in India.

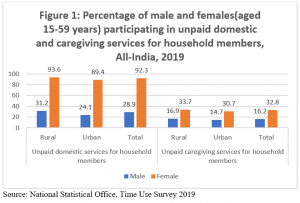

Figure 1 shows the magnitude of unpaid housework and caregiving burden on women. While more than 90% of women were engaged in unpaid domestic services, only around 30% of men were similarly engaged and this gap was more pronounced in rural than urban areas. Further, while nearly a third of women provided unpaid caregiving services for household members, less than a fifth of men were involved in this activity. The proportion of men involved in unpaid caregiving was slightly higher in rural than urban areas.

READ I NSO data: Unemployment rate falls, but, women participation still lags behind

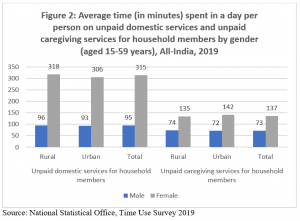

In addition to the high level of participation in unpaid housework, Figure 2 reveals that women also spend longer hours on domestic services (nearly 5 hours in a day) and caregiving (nearly 2 hours in a day) compared with men (almost 1.5 hours on domestic services and 1 hour on caregiving).

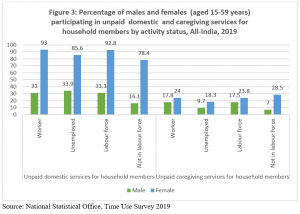

The disproportionate burden of unpaid housework does not diminish with workforce participation. Figure 3 shows that a larger percentage of women workers (93%) than men (31%) were engaged in unpaid housework. Also, participation in unpaid housework was highest among women workers than women who were unemployed or not in the labour force. Unpaid caregiving responsibilities were also quite high among women workers. This suggests that the double burden of housework and work participation could be a reason for women exiting the workforce prematurely.

READ I Crimes against women: What causes the rise in gender-based violence

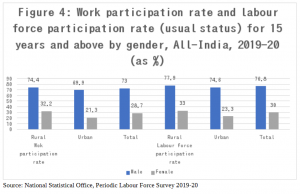

In India, literacy rate (7 years and above) among males was 85.2% and females was 71.5% in 2019-20 (PLFS 2019-20). The proportion of males who had completed secondary schooling and above was 44.2% and 32.7% among females. Figure 4 shows the huge gender gap in work participation (15 years and above) with nearly three fourths of men and less than 30% of women in the workforce. Further, female work participation was lower in urban than rural areas.

Women workers earn much less than men whether employed as regular workers, casual labour or self-employed. While gender discrimination in the labour market is one of the important factors behind lower earnings among women, cultural norms that trap women into long hours of housework is another crucial factor. The time spent on employment and related activities was lower among women (nearly 6 hours) when compared to men (nearly 8 hours).

Related to lower wage earnings among women compared with men, information from National Family Health Survey 5, 2019-21 (NFHS) clearly highlights that even when women earn wages, nearly half of them reported that they earn less than their husband and only around a fifth of them had control over the decision on how to utilise their own earnings.

Unpaid housework weighs on labour force participation

The overwhelming burden of housework and caregiving responsibilities accompanied by an absence of paid work, employment in low paid work or exit from paid work, which creates a perception of being second class economic citizens, could result in immense amount of mental stress among women. This is reflected in a large share of housewives who die by suicide.

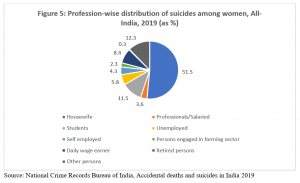

While male suicide mortality rate is higher than that of females, data on suicide by profession from accidental deaths and suicides in India 2019 reveal that among the 41,493 women who died by suicide, housewives accounted for the highest number (21,359). Figure 5 displays the percentage distribution of suicides among women by their profession. The category housewife accounted for half the share (51.5%) of total female suicides, followed by students (11.5%) and daily wage earners (8.4%).

Family responsibility functions as a penalty or a tax on women’s work. In fact, women pay the price of male work participation as it is their unpaid housework which involves time and physical effort that allows men to work. Society valorises unpaid housework by women and there is no discussion on sharing of housework and caregiving by men and women. Besides, some political parties promised a cash transfer to housewives which will only serve to entrap women into slavery.

It is time policy makers in India woke up to the problem of the Great Indian House Trapand initiate measures to encourage sharing of housework, provision of decent childcare facilities, regulate labour market gender discrimination and enabling equal opportunity to participate in the workforce to break this trap.

(Dr Gayathri Balagopal is an independent researcher based in Chennai. She works on social protection and health.)