India needs consistent sin tax regime: India’s public health spending, at just 1.3 per cent of GDP, remains one of the lowest among G20 countries. This is despite repeated claims of health being a national priority, and the launch of flagship programmes such as Ayushman Bharat and digital health missions. Meanwhile, lifestyle diseases—driven by rising consumption of tobacco, alcohol and sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs)—have quietly become the dominant cause of premature death and disability.

The economic toll is rising: higher household medical bills, lost productivity, and a cumulative intergenerational health burden that will weigh on future earnings and savings. The need for a coherent, nationwide health-financing strategy is urgent. And among the tools available, none is more underutilised—or more politically neglected—than health taxes.

READ I Dalai Lama succession: Uncertain years ahead for Tibet

Global push for corrective taxation

At the UN Conference on Financing for Development held in Seville in July 2025, the World Health Organisation launched a major new initiative: the “3 by 35” plan. It calls on countries to raise the real retail price of tobacco, alcohol, and sugary drinks by 50 per cent by 2035, using targeted and inflation-indexed sin taxes. Crucially, the proposal reframes these levies not as moral statements but as mechanisms to fund the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially universal health coverage.

The initiative has secured the backing of the World Bank, Bloomberg Philanthropies, and several member states. It presents a practical model for governments—especially fiscally constrained ones—to mobilise domestic resources without foreign borrowing or structural adjustment programmes.

Sin taxes make economic sense

Health taxes, once dismissed as “nanny state” interference, are now supported by a growing body of evidence. The goals are simple: discourage harmful consumption and raise revenue for public goods. According to WHO estimates, well-designed health taxes could generate over $1 trillion globally by 2035.

Experience bears this out. Between 2012 and 2022, over 140 countries increased sin tax on tobacco products, leading to a 50 per cent rise in real prices and significant declines in smoking rates. A 10 per cent increase in the price of sugar-sweetened beverages cuts consumption by 15 per cent, according to a meta-analysis of 62 studies. Mexico saw a 12 per cent drop in soda sales, South Africa recorded a 29 per cent fall in sugary drink intake, and the UK achieved product reformulation by manufacturers—all following the introduction of sugar taxes.

The benefits are clearest among lower-income groups, who are more vulnerable to tobacco- and alcohol-related diseases. When paired with social spending, health taxes are not only efficient but also equitable.

India’s inadequate sin tax regime

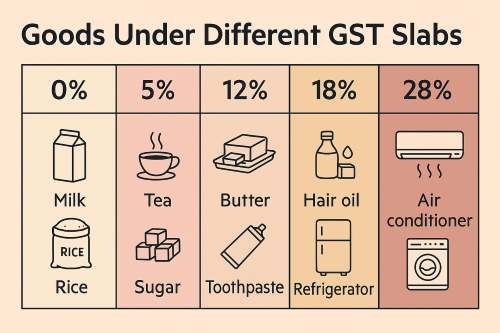

India’s current sin tax regime lacks consistency and health focus. Tobacco products like bidis, widely consumed in rural India, are lightly taxed—despite being more harmful than cigarettes. Alcohol taxation is left to state governments and is often driven by revenue needs, not public health considerations. And while sugary drinks are taxed under the GST at 18–28 per cent, there is no specific excise duty linked to their sugar content.

This fragmented system fails on both counts: it doesn’t disincentivise harmful consumption effectively, and it leaves potential revenue untapped. A more rational approach would link tax rates to the actual quantity of harmful ingredients—such as nicotine, ethanol, or added sugar—while indexing them to inflation and income growth to preserve their deterrent effect.

A case for reform and revenue recycling

Health taxes work best when paired with transparency and targeted redistribution. Earmarking revenues for nutrition programmes, school meals, rural health centres or cancer care can turn a regressive levy into a progressive policy. Countries like the Philippines and Thailand have shown that revenues from tobacco taxes, when channelled into healthcare subsidies, can enhance public trust and improve outcomes.

Claims that health taxes lead to job losses, inflation or disproportionately hurt the poor often fail under scrutiny. These products are non-essential and discretionary. Reducing their use lowers disease burdens, especially among the poor, who bear the brunt of the health costs but benefit most from reduced consumption. Redirecting revenues into social services amplifies the redistributive effect.

Need technically sound policy design

The structure of sin taxes matters as much as their presence. The WHO and World Bank both recommend specific taxation—a fixed amount per unit of harmful ingredient—as more effective than ad valorem (percentage-of-price) systems. This approach simplifies enforcement, reduces loopholes, and avoids regressivity.

Moreover, taxes must be indexed to inflation and income growth, to retain their real value over time. Without this, the deterrent effect erodes, and consumption rebounds. Finally, citizen buy-in improves when revenues are explicitly linked to health and nutrition goals, not simply absorbed into general budgets.

A window for political courage

India’s past reluctance to impose robust sin taxes stems largely from political caution. But post-Covid, the politics of health has changed. Citizens better appreciate the value of preventive investment. The economic case has also sharpened: rising debt, urban health stress, and the need for new domestic revenue sources make health taxes a logical tool.

A uniform national health tax regime, backed by inter-ministerial coordination and transparent use of funds, can offer both fiscal space and developmental dividends.

The country’s health crisis today is not just about access—it is about resilience, equity, and sustainability. Health taxes offer a rare alignment of economic logic and social justice. They reduce what harms and finance what heals. Framed well, they are not punitive but transformative.

The WHO’s “3 by 35” framework gives India a roadmap to act boldly and wisely. The choice is no longer between taxation and liberty, but between prevention and paralysis. It is time to tax harm—for the greater public good.

Dr Chitra Saruparia is Assistant Professor (Economics), Assistant Dean (UG Council), and Director, Centre for Economics, Law and Public Policy at National Law University, Jodhpur.