India’s GDP growth: India has set itself an audacious deadline: evolve from a middle-income nation into a fully developed economy by 2047, the centenary of Independence. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s address to the 10th Governing Council meeting of NITI Aayog termed the task as a joint enterprise of New Delhi and the states. In an era of fragile global demand, much of the required momentum must come from within—and from every corner of the federation.

Lifting GDP per capita from roughly $2,500 today to about $14,000 by 2047 demands compound growth of 7–8 per cent a year for more than two decades. Achieving that pace will hinge on narrowing the vast economic gulf that runs east to west and north to south. Some Indian states are already punching at middle-income weight; others remain stuck in low-productivity traps. Unless the laggards accelerate, they will act as a drag on the national project.

READ I FDI crash exposes India’s capital flight risk

Lessons from the pacesetters

Karnataka, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat and Telangana show what is possible when policy and politics pull in the same direction. Karnataka rides a services juggernaut built on Bengaluru’s tech ecosystem; Tamil Nadu’s diversified factories make everything from cars to wind turbines; Gujarat couples’ fiscal discipline with an entrepreneurial culture; Telangana’s emphasis on industrial parks and high-value crops has delivered quick returns. Their common thread? Relentless investment in infrastructure, urbanisation and a business environment that welcomes capital.

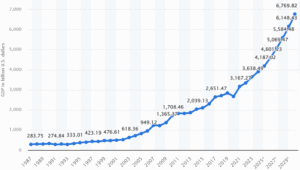

Gross domestic product in current prices from 1987 to 2030 (in $ billion)

Elsewhere the picture is less buoyant. Bihar, Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh continue to wrestle with weak human-capital bases and threadbare infrastructure. Punjab offers its own cautionary tale: once an agricultural powerhouse, it slipped down the income league because it never pivoted from paddy and wheat, while neighbour Haryana sprinted ahead by courting industry around Gurgaon. These divergences are already reshaping each state’s share of national GDP.

What the GDP growth data tell us

A September 2024 paper for the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council by Sanjeev Sanyal and Apoorva Arora mapped states along two axes—share in national output and relative per-capita income. Western and southern states dominate both measures; eastern India still lags; maritime states (with the lone exception of West Bengal) are outperformers; Odisha stands out for a two-decade leap. Liberalisation rewarded regions that entered the 1990s with sound infrastructure, industrial depth and investor-friendly governance.

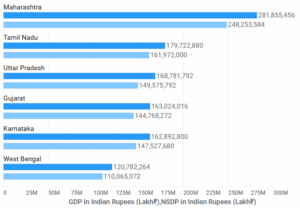

Indian states and union territories by GSDP

Reserve Bank of India research has sharpened the diagnosis. A 2022 risk analysis warned that pandemic-era subsidies, power-sector bail-outs and populist “freebies” have stretched several state balance-sheets. Rising debt and shrinking tax buoyancy recall the early stages of Sri Lanka’s crisis, the authors cautioned, even if most Indian states remain solvent for now. The RBI’s 2023 study of state budgets pressed for a broader local tax base, fuller user charges and tougher scrutiny of contingent liabilities—steps essential if states are to finance the roads, schools and clinics their citizens now expect.

Another 2024 RBI paper on business-cycle synchronisation found that western and southern states have moved increasingly in lock-step with the national economic pulse, largely because they share similar sectoral mixes and trading ties. Eastern and some northern states, by contrast, still dance to different rhythms, underscoring why one-size-fits-all policy often misfires.

Four pillars, one goal

First, industry must become the front-rank growth engine. States need reliable power, rapid clearances and industrial corridors that link regional clusters to global supply chains. That is how Gujarat turned coastal highways into conveyor belts for exports and how Tamil Nadu climbed the auto and electronics value chain.

Second, agriculture has to move beyond calorie security. The priority is value: horticulture, dairying, aquaculture and food processing that lift farm incomes without exhausting groundwater. Digital extension services and precision irrigation can help smallholders tilt from subsistence to surplus.

Third, services deserve equal billing. Vibrant urban centres such as Bengaluru or Hyderabad show how IT, design, health care and tourism feed off each other. Cities that invest in liveable housing, transit and culture attract the skilled migrants whom knowledge economies crave.

Fourth, fiscal policy underpins everything else. States must impose hard budget constraints, publish transparent accounts and modernise revenue collection—from tighter GST compliance to realistic user fees for water and power. Credible finances lower borrowing costs and create space for productive capital spending.

Machine-learning tools can reinforce each pillar—predicting crop yields, flagging tax evasion or optimising hospital staffing—but technology is an amplifier, not a substitute, for clear-eyed governance.

Cooperative federalism

The Centre can help by rewarding reform with larger untied transfers, accelerating GST compensation for early adopters of digital invoicing and ensuring that the next Finance Commission calibrates formulae to incentivise growth and prudence. Equally, successful states should be more willing to share best practice with neighbours; India’s single market will be stronger if Bihar prospers as surely as Gujarat.

Twenty-two years is a blink in development time. Yet India’s demographic window—its youthful workforce—will begin to narrow by the 2030s. Delay is no option. Prime Minister Modi has issued the call. It is now for state capitals, the Finance Commission and every public institution to treat the 2047 target as a hard deadline, not a slogan. If they do, Viksit Bharat will be more than a catch-phrase; it will be a shared national inheritance.

Dr Charan Sigh is a Delhi-based economist. He is the chief executive of EGROW Foundation, a Noida-based think tank, and former Non Executive Chairman of Punjab & Sind Bank. He has served as RBI Chair professor at the Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore.