VB-GRAM-G and Karnataka’s shrinking MNREGA access: On December 18, 2025, the Union government introduced the Viksit Bharat – Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin) Bill, 2025, replacing the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA). The bill raised the statutory ceiling from 100 to 125 days of unskilled manual work per rural household member, projecting the reform as part of the Viksit Bharat 2047 framework.

The legal expansion is unambiguous. Its practical relevance is not. In Karnataka, where MNREGA remains a core employment buffer for households with limited labour market alternatives, the question is narrower- does a higher ceiling translate into more accessible workdays? Recent trends suggest the opposite.

READ | MGNREGA recast: Why the mission model risks rural jobs

VB-GRAM-G reform: Shrinking coverage, not falling demand

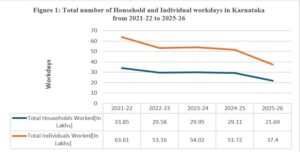

In 2021–22, MNREGA in Karnataka provided employment to 33.85 lakh households and 63.61 lakh individuals. By 2024–25, household coverage had fallen to 29.11 lakh. In 2025–26, it dropped sharply to 21.69 lakh households. This is a 36 percent contraction in household coverage in five years (Figure 1).

The decline is sharper at the individual level. Participation fell from 63.61 lakh workers in 2021–22 to 37.4 lakh in 2025–26 (Figure 1). Fewer individuals per registered household are accessing work. This pattern is consistent with rationing, not with a sudden tightening of rural labour markets.

Low intensity makes higher ceilings irrelevant

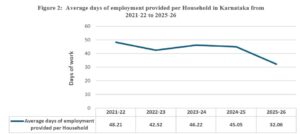

Employment intensity has weakened alongside coverage. Average days of employment per household declined from 48.21 days in 2021–22 to 32.06 days in 2025–26 (Figure 2). At this level of access, raising the statutory limit to 125 days is arithmetically irrelevant to most households.

The erosion is sharper at the top end of entitlement. Households completing 100 days of work fell from 1.76 lakh in 2021–22 to 7,700 in 2025–26 (Figure 3). The share declined from 5.2 percent to 0.04 percent. If households cannot exhaust the existing entitlement, expanding the ceiling does not alter livelihood security.

Supply contraction, not demand exhaustion

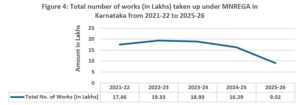

The contraction is visible on the works side. New works declined from 17.46 lakh in 2021–22 to 9.02 lakh in 2025–26. Ongoing works fell from 11.85 lakh to 5.99 lakh over the same period. This is a supply constraint. Fewer sanctioned works mean fewer workdays, irrespective of registered demand.

READ | MGNREGA dilution risks undermining the right to work

This is not a behavioural shift in labour participation. It is an administrative and fiscal bottleneck in work generation.

One part of the explanation lies upstream, in the financing mechanics of the programme. MNREGA is demand-driven in statute but cash-driven in execution. Work creation depends on timely central releases and predictable reimbursement of wage and material costs. When releases are delayed or calibrated conservatively, states tend to ration works rather than accumulate unpaid liabilities.

Karnataka’s contraction in works and employment is consistent with this behaviour. The decline therefore reflects not an exhaustion of rural demand but the limits imposed by centrally mediated funding flows on a scheme whose legal guarantee outpaces its fiscal backing.

READ | MGNREGA reform risks weakening rural India’s last safety net

Distributional consequences

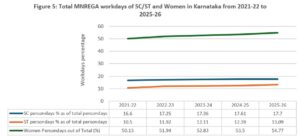

The composition of employment underlines what is at stake. In 2025–26, women accounted for 54.77 percent of person-days, up from 50.13 percent in 2021–22. Scheduled Castes contributed 17.7 percent and Scheduled Tribes 13.09 percent, both rising steadily over five years (Figure 4).

These are not marginal beneficiaries. Any contraction in work availability produces direct distributional effects on vulnerable groups that rely on MNREGA as a fallback labour market.

Entitlement inflation, access deflation

Karnataka now presents a policy contradiction. Legal entitlements are expanding while access is contracting. Average employment stands at 32 days. Completion of 100 days has nearly vanished. Works generation is falling.

In this setting, raising the ceiling to 125 days is a symbolic reform unless accompanied by a structural expansion in sanctioned works, administrative capacity, and fiscal provisioning. Without that, VB–GRAM–G risks becoming a programme of entitlement inflation and access deflation—more rights on paper, fewer days in practice.

A Sajitha is Assistant Professor of Economics, Christ University, Bengaluru.