Debt crisis threatens Global South economies: A disturbing shift has unfolded in global finance: developing nations are now paying more to service debts owed to China than they receive in fresh loans. A Boston University study published this week found that net debt transfers from China to developing countries turned negative in 2022 and 2023, with borrowers repaying nearly $3.9 billion more each year than they borrowed. This is not merely a technical rebalancing of accounts. It signals a profound crisis of debt sustainability — one that could sap growth, erode fiscal stability, and slow the green transition in the Global South.

Yet it would be facile to reduce this phenomenon to debt-trap diplomacy, the term often used to describe China’s opaque, collateral-heavy lending. That narrative paints developing countries as helpless victims of a predatory creditor. The truth is more inconvenient: many nations have willingly stepped into the trap, seduced by easy money and blinded by weak governance and due diligence. The debt crisis of today is as much a product of borrower behaviour as of Chinese design.

READ I India at the heart of global HIV strategy

China – capital provider to debt collector

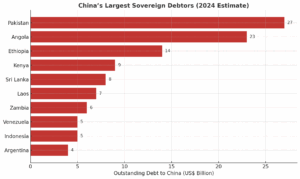

Over the last decade, China’s role as the world’s largest bilateral creditor has changed fundamentally. Once hailed as the financier of roads, ports and power grids, it is now increasingly acting as a debt collector. According to the Lowy Institute, repayments and interest costs have outpaced new disbursements. The poorest 75 nations, by Lowy’s count, are expected to pay a record $22 billion in debt service to China in 2025 — a stark reversal of the previous decade’s credit boom.

This is compounded by opacity. AidData estimates that up to $1.3 trillion in Chinese loans are missing from official databases such as the World Bank’s, which record only $123 billion in public and public-guaranteed debt to China. AidData research shows that Beijing’s lending ecosystem — spanning policy banks, state-owned enterprises and commercial lenders — operates through parallel financial structures that obscure the true scale and terms of exposure. This lack of transparency grants China extraordinary leverage, allowing it to refinance or restructure debt without multilateral oversight.

But opacity is not deception alone; it is complicity when borrowers ignore the warning signs. Many governments, fully aware of these conditions, still signed agreements because Chinese loans came with fewer governance strings and faster disbursements. The convenience came at a heavy price.

Governance failures and debt crisis

China may have provided the money, but the governance failures that led to the debt crisis are largely homegrown. Across Asia and Africa, borrowing decisions have been guided more by political vanity than by economic logic. Projects were pursued for their grandeur, not their returns. Institutions responsible for appraisal, audit, and procurement were sidelined or silenced.

In Pakistan, the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor became a byword for both ambition and mismanagement: power projects and motorways were built, but contractual opacity and inflated costs left the economy struggling to service debt. In Sri Lanka, it was domestic profligacy and reckless fiscal expansion, not Chinese loans alone, that precipitated default. Analysts have noted that Chinese lending formed less than a fifth of Sri Lanka’s external debt at the time of crisis. Kenya’s Standard Gauge Railway — financed by the China Exim Bank — has become another cautionary tale of weak oversight and poor financial projections.

These examples underline a simple truth: debt distress flourishes in the shadow of weak governance. When state institutions are pliant, oversight is absent, and politics rewards short-term spectacle over long-term prudence, debt becomes destiny.

The due diligence deficit

A recurring feature in these crises is the absence of rigorous due diligence. Borrower nations rarely subjected large infrastructure loans to the kind of stress testing or cost–benefit evaluation that prudent fiscal management demands. Projects were approved without realistic projections of revenue or foreign-exchange generation, and with little assessment of contingent liabilities.

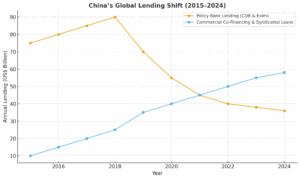

The nature of Chinese finance has changed as well. Research by ODI Global shows that Beijing’s policy banks — once the backbone of the Belt and Road Initiative — have reduced concessional lending in favour of commercial co-financing and syndicated loans led by state-owned or private Chinese banks. These instruments carry shorter maturities, variable interest rates and limited grace periods. They shift repayment risk squarely onto the borrower.

Many governments, desperate for funds, agreed to conditions that subordinated their fiscal sovereignty. Some allowed commodity revenues or port earnings to be placed in offshore escrow accounts controlled by Chinese creditors — an arrangement revealed in AidData’s debt-contract analysis. Others accepted confidentiality clauses that barred public scrutiny. When domestic institutions sign such contracts without parliamentary approval or public debate, the debt crisis ceases to be a diplomatic scheme and becomes a domestic failure of accountability.

The debt crisis is not solely of China’s making

There is no doubt that China’s opaque practices and geopolitical ambitions have contributed to the debt crisis. But to treat every distressed borrower as a victim of Beijing’s machinations is misleading. Many countries entered into these arrangements willingly, driven by the allure of fast money and the political optics of development.

The evidence suggests that China’s so-called “debt-trap diplomacy” is less a deliberate conspiracy and more an opportunistic response to borrower weakness. In Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port deal, for instance, China gained a long-term lease, but at the cost of investing further capital and managing an unprofitable facility — hardly a clear-cut case of asset seizure. The broader lesson is that sovereignty is rarely stolen; it is more often mortgaged through poor decision-making and fiscal indiscipline.

Governance failure, not Chinese cunning, is the first domino in this cascade. When nations mortgage their future revenues to build projects of questionable utility, they are not victims — they are accomplices in their own debt entrapment.

Reform, resilience and realignment

The way forward demands less rhetoric about the debt crisis and more focus on reform. Developing countries must first bring transparency to their borrowing. Every major credit contract — especially those involving foreign lenders — should be disclosed, debated and audited. Sunshine is the most potent disinfectant against unsustainable commitments.

Next, they must rebuild the institutional machinery of appraisal and evaluation. Independent agencies with technical expertise must scrutinise projects for cost-benefit realism, environmental compliance, and fiscal risk. No foreign loan should bypass this process, however attractive the headline figures.

Third, debt ceilings must reflect not political optimism but macroeconomic reality. Borrowers should account for currency fluctuations, repayment contingencies and potential revenue shortfalls when taking on new debt. Prudence must replace populism.

Diversification of financing sources is equally essential. A mix of concessional loans from multilateral development banks, regional funds and climate-finance institutions can offer cheaper and more stable capital than reliance on a single creditor. Borrower nations should also press for a global consensus on debt transparency, binding all major lenders — including China — to uniform reporting and restructuring standards under the G20 or the Paris Club.

Finally, the most enduring solution lies within. Countries that raise adequate domestic revenues are less vulnerable to external leverage. Strengthening tax systems, widening the base, and improving compliance can reduce dependence on foreign borrowing and bolster fiscal sovereignty.

The debt crisis across Africa and Asia are a warning that sovereignty today is tested not only on the battlefield but in the bond market. External creditors, however powerful, can entrap only those who walk in unguarded. China’s lending practices are indeed opaque, but opacity finds purchase only where domestic governance is weak.

If developing nations wish to escape the next cycle of debt distress, they must build the institutions, discipline, and transparency that make borrowing a tool of growth, not a snare of dependence. The debt trap is not inevitable. It begins — and can end — at home.

Anil Nair is Founder and Editor, Policy Circle.