India’s economic journey can be read in two unequal halves: the first seventy‑five years since Independence, and the next twenty‑five years that will decide whether the country achieves its Viksit Bharat goal by 2047. Savings and investment have risen dramatically and the structure of output has shifted from farms to factories and services, but growth has not always kept pace. The task ahead is to understand the wedge between resources and results — and to close it with efficient, inclusive policy.

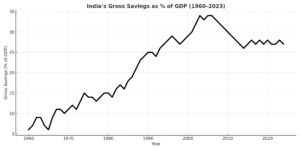

A useful way to summarise seventy‑five years is through three ratios: the saving rate, the investment rate, and the incremental capital‑output ratio (ICOR). At Independence, gross domestic saving (GDS) was near the low teens as a share of GDP; in the 2000s–2020s it has hovered around one‑third. Yet trend growth has climbed only from roughly 4% in the 1950s to about 6–7% recently. When ICOR rises — because projects are delayed, misallocated, or overly capital‑intensive — each percentage point of growth demands more capital, dulling the impact of higher savings.

Gross domestic savings as % of India’s GDP

Recent data bear this out: GDS has been close to 30–33% of GDP in recent years, while long‑run ICOR estimates often lie between 3.5 and 4.5, with cyclical spikes and dips.

READ I Private investment in uranium mining and India’s energy future

Six phases and the policy thread

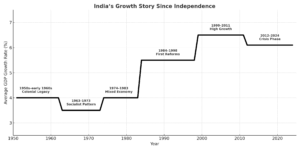

The post‑1950 story can be sketched in six phases. A low‑saving, agriculture‑heavy start produced about 4% growth thanks to a modest ICOR. The socialist‑control era of the mid‑1960s to early‑1970s raised ICOR and slowed growth below 3.5%, not because of cultural destiny but because controls, licensing and heavy‑industry bias hurt efficiency. A mixed‑economy phase through the early‑1980s restored balance as private investment rose and ICOR fell.

The first reform wave of the mid‑1980s to the 1990s — punctuated by the 1991 liberalisation — pushed savings toward 18% and investment above 20%, lifting trend growth to around 5.5%. From the late‑1990s to the global financial crisis, investment breached 30% and growth accelerated to about 6.5% despite external shocks. Since 2012, repeated global crises — including the Eurozone slowdown, commodity swings, and the pandemic — have kept the average near 6%, even as savings stayed robust. The common thread is unmistakable: policy that improves the efficiency of capital turns resources into results; policy that chokes competition or delays projects raises ICOR and depresses growth.

What the national accounts say

The structural transformation is clear in national accounts. Services now provide the largest share of gross value added, industry is second, and agriculture about one‑sixth. On the demand side, private consumption is roughly three‑fifths of GDP while fixed investment is about one‑third. Public capital expenditure has picked up to crowd‑in private capex, but translating investment into output still depends on timely clearances, reliable logistics and predictable regulation.

Per capita income has grown faster than headline GDP because population growth has declined persistently — from above 2% in the 1970s to under 1% today. With GDP at 6–7% and population growth on a downward trajectory, per capita income can compound near 5% a year, doubling roughly each decade—provided job creation and skills keep pace.

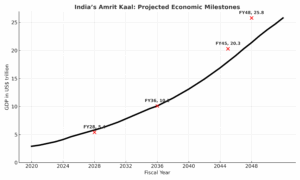

Viksit Bharat 2047: Promise vs premises

Long‑horizon forecasts differ by assumptions, but they share one idea: India’s potential is large if policy stays disciplined. A commonly cited goals of Viksit Bharat — the economy near $26 trillion (market exchange terms) by 2047; third‑largest economy by 2027 and second‑largest by 2075. Such numbers are not inevitabilities; they are conditional promises — on investment efficiency, human capital, and the rule of law.

Three priorities follow from the history. First, raise the efficiency of investment. Centre and states should concentrate public spending on health, education and logistics, while speeding clearances and enforcing contracts. Rigorous project appraisal and time‑bound execution will lower ICOR and lift growth without demanding ever‑higher savings.

Second, ensure equity alongside expansion. Inequalities—regional, urban‑rural, and between formal and informal work—cannot be addressed by growth alone. More and better spending on primary healthcare, foundational learning and targeted skilling is non‑negotiable.

Third, create jobs at scale. India needs a twin engine: labour‑intensive manufacturing (textiles, food processing, electronics assembly, light engineering) and a continued upgrade of services, including global capability centres and tourism. Policies that increase female labour force participation—safe transport, childcare, flexible work—are essential to convert the demographic window into a dividend.

India has climbed the growth mountain in fits and starts, more often constrained by the efficiency of capital than by its supply. With savings near one‑third of GDP and a young workforce, the ingredients for 7% growth exist. Achieving it will require fiscal discipline, predictable regulation, competitive markets and a relentless focus on human capital. If policy converts resources into results—lowering ICOR, broadening opportunity and creating jobs—the Viksit Bharat 2047 milestone will be marked not only by size, but by shared prosperity.