India’s toy industry, once awash in low-cost imports and subject to little regulation, is undergoing a quiet transformation. The catalyst: the Toys (Quality Control) Order, 2020, issued by the department for promotion of industry and internal trade. This regulatory move requires all toys sold in India — whether produced domestically or imported — to comply with the Bureau of Indian Standards norms. These standards are harmonised with the benchmarks of the International Organisation for Standardisation, giving Indian manufacturers a quality framework to compete globally and access export markets more confidently.

The policy signals a shift from a laissez-faire approach to one rooted in quality assurance and consumer safety. It also seeks to reduce India’s dependence on imports, especially from China, while reviving domestic toy industry through regulatory discipline.

READ I Crypto governance gap threatens the $4 trillion market

Trade patterns reflect the shift

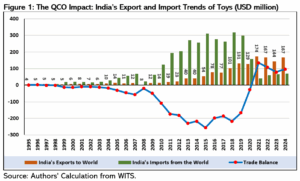

The implementation of the QCO has redrawn India’s toy trade profile. Exports rose from $131.5 million in 2019 to $167 million in 2024. A more telling shift occurred in 2021 when toy exports touched $174 million, compared with $129 million the previous year. Since then, India has consistently exported toys worth over $140 million annually—indicating a new floor has been established in terms of global market competitiveness.

The impact on imports has been equally striking. From a peak of $318.9 million in 2018, toy imports fell to $157 million in 2020 and further plummeted to just $40 million in 2021. For the first time in decades, India registered a trade surplus in toys: from a deficit of $256.62 million in 2015 to a surplus of $134.2 million in 2021 and $96.44 million in 2024.

The United States leads demand

The US has emerged as India’s largest toy export destination, with exports increasing from $1.25 million in 1995 to $78.6 million in 2024. Its share of India’s toy exports has risen to nearly 47%, up from 31.86% three decades ago. The UK, Australia, and the UAE have also become significant destinations.

Meanwhile, China’s dominance in the Indian toy market has weakened. Once accounting for nearly 90% of India’s toy imports, China’s share has dropped by 23.8% since the QCO was enforced. In contrast, imports from the EU have increased by 5% during the same period, suggesting these regions have adjusted swiftly to the new standards.

The export gains are most visible in categories governed by HS codes 95030010 (Electronic Toys) and 95030020 (Non-Electronic Toys). Exports of electronic toys rose from an average of $3.73 million during 2017–2019 to $18.01 million between 2021 and 2024. Non-electronic toys saw an even more dramatic rise—from just $0.58 million to $40.18 million over the same periods. In contrast, exports of plastic dolls (HS code 95030030) declined from an average of $56.54 million to $44.71 million, suggesting that gains have not been uniform across categories.

A new map of trade and manufacturing

India’s toy trade is gradually moving away from low-cost sourcing hubs and aligning itself with higher-standard export markets. Imports from the EU and EFTA countries, which already conformed to stringent standards, have grown in relative terms. This hints at a reconfiguration of India’s global supply chain in favour of quality-compliant economies.

Data from Panjiva reveals that both domestic and foreign firms have benefitted from these shifts. DHL Logistics was the top exporter, with toy exports worth $20.47 million. Indian-owned firms like Micro Plastics, Damco India, and Sar Transport Systems also featured in the top ten, with average exports ranging from $2.76 to $2.94 million. On the import side, many firms are subsidiaries of global players based in the US, Germany, Luxembourg, and Denmark—showing how multinational supply chains have adapted to India’s new regulatory regime.

Not protectionism, but strategic regulation

The QCO, though regulatory in nature, has avoided the trap of crude protectionism. Instead, it has functioned as a targeted tool to improve safety and catalyse competitiveness. Countries such as the US, Germany, and Denmark have not been disadvantaged; on the contrary, their firms—accustomed to high safety standards—have integrated smoothly into India’s compliance regime.

By aligning domestic standards with global norms, the QCO serves not as a barrier to trade but as a bridge. It allows Indian manufacturers to meet export requirements more easily while filtering out substandard imports. This dual-purpose approach—protecting consumers while nurturing global competitiveness—is a notable departure from the usual tariff-led trade measures.

Lessons from toy industry reboot

The apparent success of the QCO in the toy sector may offer a template for similar interventions in other industries. Well-designed technical regulations—transparent, enforceable, and harmonised with international norms—can simultaneously advance public interest and economic goals. But for such measures to succeed more broadly, India must address the structural challenges faced by smaller manufacturers.

Most BIS testing labs are located in urban areas, leaving small-town producers struggling with logistics and compliance costs. Without decentralised support infrastructure, the regulatory burden risks tilting the playing field in favour of large firms with deep pockets and foreign linkages.

India’s toy industry transformation is no longer just about phasing out hazardous imports. It is emerging as a case study in smart regulatory design—one that can balance trade, industrial revival, and consumer protection.

As global debates over non-tariff barriers and product safety grow more intense, India’s measured approach to toy quality control might be the pragmatic model other developing economies are looking for.

Murali Kallummal is Head of Administration at the Centre for Research on International Trade (CRIT) and Professor at Centre for WTO Studies (CWS), IIFT, New Delhi. Simran Khosla, and Ankit Kundu are Associate and Young Professional, respectively at the CWS.

Murali Kallummal is Professor, Centre for WTO Studies, CRIT, IIFT, New Delhi. Views are personal.