Organisations, nations, and society at large reserve their efforts for gender diversity to lip service on the International Women’s Day. Gender diversity cannot be achieved through on-and-off efforts, but requires ongoing intervention and cultural shifts. Research supports the notion that a country can significantly benefit from increased female participation in the workforce. The IMF suggests that aligning India’s female labour force participation rate with that of men could boost India’s GDP by 27%. The labour force participation rate (LFPR) measures the percentage of the working-age population that is either employed or actively seeking employment.

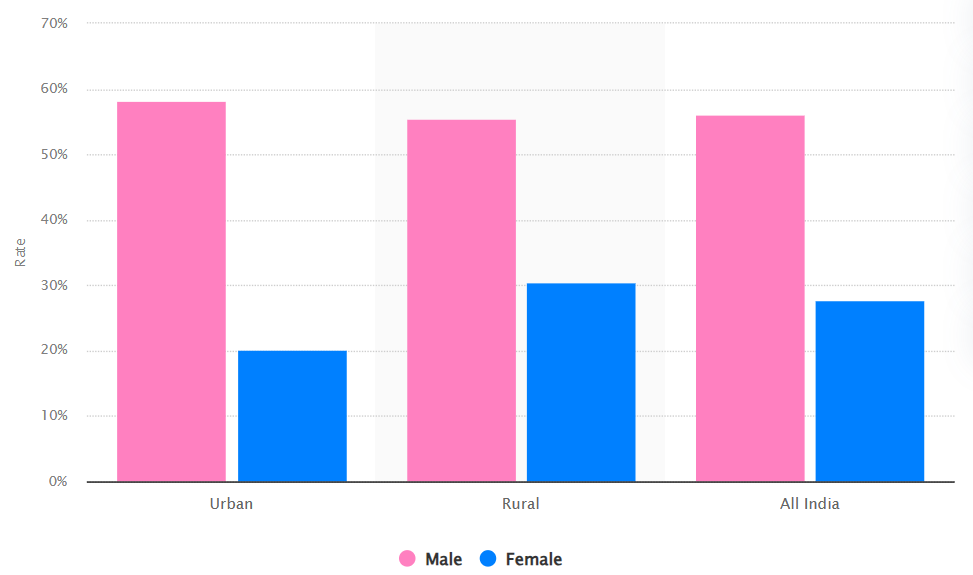

India’s female labour force participation rate has been historically lower than the global average — about 28% compared with 50% globally, while male LFPR stands at 78.5%, surpassing the global average of 73% (ILO). This disparity has resulted in a 40% gap between male and female LFPR in India, compared with a global figure of 25%. Although LFPR of females peaked at 30.5% in the early 2000s, it has declined since then despite an economic boom, averaging 26% post-financial crisis until 2017. However, the past five years have seen a sharp increase in India’s FLFPR from 23% in FY18 to 37% in FY23, according to the periodic labour force survey.

READ I Labour market: Concerns over informalisation of workforce

Rate of labour participation as of June 2023

Is India experiencing the well-documented U-shaped female LFPR curve? Claudia Goldin’s Nobel Prize-winning research in Economic Sciences in 2023 explored the dynamics of female labour force participation in relation to economic growth, challenging the notion of a positive linear relationship. Her findings indicate that at lower economic development levels, women’s workforce participation is higher, particularly in agriculture-based economies.

As economies develop and incomes rise, female participation in low-paid or unpaid roles tends to decrease as women withdraw from the workforce. However, as the manufacturing and services sectors expand and female education improves, women enter the workforce, attracted by the opportunities in skilled and higher-paying jobs.

Rising female labour force participation

The increase in India’s FLFPR, particularly in rural areas, raises the question: is India at the ascending phase of a U-shaped FLFPR curve, where economic growth and the availability of skilled jobs are driving the trend? A 9.5% surge in FLFPR between FY18 and FY23 was largely due to increased female participation in rural areas, from 24.6% to 41.5%, while urban FLFPR rose modestly from 20.4% to 25.4%.

The jump in rural FLFPR can be attributed to the growth in self-employed women, encompassing own-account workers and unpaid household enterprise helpers. Despite this increase, the proportion of women in regular/salaried jobs has remained stable, suggesting that the rise in FLFPR is fueled by self-employment rather than an increase in salaried positions.

This trend indicates two main points: a notable rise in women’s workforce participation, especially in self-employment in rural areas, and a nearly constant proportion of women in salaried jobs, implying that FLFPR growth is driven more by self-employment than job availability. However, this rise in self-employed women could signal an increase in female entrepreneurship, a potentially positive development.

Policy interventions play a crucial role in closing the gender gap in labour force participation. The government and private sector can implement several measures to encourage female participation in the workforce. For instance, introducing more flexible working hours and remote work options can help women balance their professional and personal responsibilities. Moreover, offering maternity leave and child care support can alleviate some of the burdens that often deter women from remaining in or re-entering the workforce.

Enhancing access to education and vocational training for women, especially in rural areas, would equip them with the skills required for higher-paying and more secure jobs. Additionally, policies aimed at promoting gender equality in the workplace, including equal pay for equal work and anti-discrimination laws, are essential for creating an environment where women can thrive professionally.

Alongside policy interventions, a shift in societal attitudes towards women’s employment is fundamental for achieving gender parity in the workforce. Cultural norms and expectations often dictate a woman’s role primarily as a caregiver, limiting her career opportunities. Raising awareness about the value of gender diversity and equality through education and public campaigns can help change these perceptions. Engaging men as allies in the quest for gender equality is also vital, encouraging shared responsibilities at home and advocating for women’s rights in the workplace. Such societal shifts, supported by policy frameworks, can create a more inclusive and equitable labour market for women in India.

Yet, caution is advised when interpreting these trends. The Azim Premji University’s ‘State of Working India 2023’ report suggests that post-Covid lockdown, the increase in female FLFPR, driven by declining household incomes, pushed more women into self-employment due to economic distress. This situation challenges the notion of a rise in high-quality self-employment for women.

Moreover, the PLFS survey for FY22 highlights that nearly 45% of women cited childcare and homemaking commitments as primary reasons for leaving the workforce, pointing to the persistent structural and societal norms that hinder women’s participation in India’s labour force. To realise its full economic potential, India must address these barriers to increase female workforce participation.

(Prachi Priya is a corporate economist based in Mumbai.)