Delhi air pollution crisis: Delhi-NCR enters each winter with the same expectation: that the State will finally treat toxic air as a public health emergency. Instead, the 2025–26 winter has produced a different truth — India’s political and administrative system has normalised hazardous air. The three pillars of the State have simultaneously stepped back from their basic responsibility to protect life in one of the world’s most polluted urban regions.

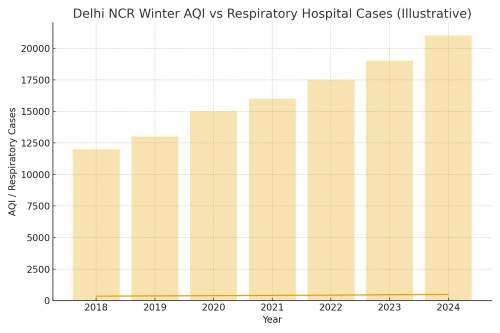

The air quality index shows that fine particulate pollution reduces life expectancy in North India by more than 8 years. During November–December, average AQI levels in the NCR often exceed 500, according to the Central Pollution Control Board. These are levels that global health agencies classify as “hazardous.” Yet the institutional response remains weak, fragmented, and predictable.

READ I Higher education: How to turn scale into quality

Legislative paralysis and weak environmental governance

Delhi air pollution crisis reflects structural governance failures rather than seasonal surprises. The legislative architecture has not kept pace with the environmental demands of a rapidly urbanising economy. India lacks a strong, enforceable framework to restrict single-use plastics, despite repeated notifications from the ministry of environment, forest and climate change. Segregation at source under the Solid Waste Management Rules remains incomplete, and landfill capacity in the NCR continues to expand.

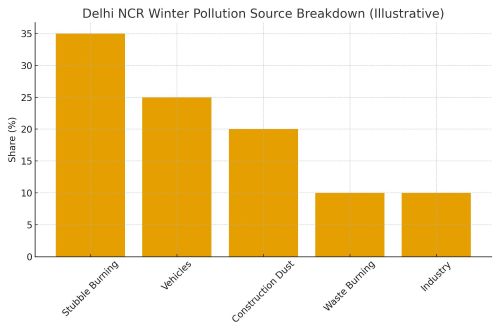

Construction norms are outdated. Real-time monitoring, dust-control systems, and green construction standards should have become mandatory years ago. The continued absence of these rules is remarkable given that construction dust contributes almost 30% of Delhi air pollution in winter months, according to the Delhi Pollution Control Committee. Stubble burning remains the most intractable problem because political incentives constrain enforcement across state borders. The annual spike in particulate matter that follows the crop cycle is the most visible symptom of this misalignment between economic incentives and environmental outcomes.

Delhi air pollution and judicial fatigue

For many years, courts offered the only meaningful intervention. The Supreme Court and the National Green Tribunal (NGT) repeatedly issued directions on construction dust, waste burning, and firecracker bans. However, the intensity of judicial engagement has diminished. The shift has come at a time when respiratory illnesses rise sharply in the NCR’s winter months. The Indian Council of Medical Research links prolonged exposure to PM2.5 with higher incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lower respiratory infections.

Weaker enforcement encourages non-compliance. When courts signal that a crisis is not urgent, day-to-day violations multiply. The problem is not the lack of laws but the absence of sustained institutional attention.

Administrative drift and breakdown of local enforcement

The executive’s failure is the most visible on the ground. Municipal bodies often report shortages of equipment and manpower. Dust suppression measures are episodic rather than continuous. Illegal construction, open waste dumping, and roadside burning occur in broad daylight. Complaints to municipal helplines and police numbers frequently go unanswered.

The stubble-burning problem captures the scale of administrative drift. ISRO satellite data shows consistent hotspots each year in Punjab and Haryana during October–November. Enforcement remains weak because deterrence is minimal and alternatives to crop residue disposal are inadequate. The pattern repeats annually without significant administrative correction.

Media as the only active institution

The media has emerged as the sole pillar maintaining vigilance. Newsrooms, researchers, and citizen journalists continue to highlight illegal dumping, stalled enforcement, and toxic hotspots. Their work has not been partisan. It has been factual and relentless.

But media attention cannot replace institutional enforcement. It can amplify public frustration and mobilise civic pressure, but it cannot implement regulations. What it can do is create a channel for collective action when formal institutions falter.

Citizen behaviour and pollution control

Any honest assessment must also acknowledge the role of citizens. Household consumption patterns contribute significantly to the pollution load. The NCR generates more than 11,000 tonnes of solid waste every day; segregation rates remain below 60%, according to the Swachh Bharat Mission dashboard. Plastics, thermocol, and disposable cups continue to dominate urban retail and social events despite restrictions.

Individual choices matter. Open dumping, construction without dust nets, indiscriminate use of firecrackers, and daily reliance on disposables create a cumulative burden that no government machinery can manage without citizen cooperation. Sustainable behaviour—reusing bottles, carrying cloth bags, composting, reporting violations—remains limited.

Institutional reform and collective responsibility

The policy lesson is straightforward: Delhi’s air crisis is not merely an environmental failure. It is a governance failure. A credible response requires three shifts.

First, modern legislative frameworks are essential—covering waste management, construction norms, and single-use plastics. Second, predictable judicial enforcement must replace episodic interventions. Third, municipal capacity must be strengthened with investment in monitoring, waste logistics, and real-time public reporting.

But systemic reforms will work only if citizens change behavioural norms. Collective action can raise political costs for inaction and reshape incentives for enforcement agencies. Civic responsibility is not a substitute for State action but a necessary complement to it.

Clean air is not a luxury in a modern economy. It is a constitutional right. Institutions must act decisively—or risk presiding over a slow-motion public health disaster.

Angira Singhvi Lodha is Partner at Khaitan and Khaitan, a leading Indian law firm.