Trump executive order on deep-sea mining: The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, adopted in 1982, remains the cornerstone of global maritime governance. It provides a comprehensive legal framework regulating the use of the world’s oceans and marine resources—from navigation rights to the sustainable management of biodiversity and seabed minerals. It also led to the creation of the International Seabed Authority, which oversees mineral-related activities in international waters—defined as the area beyond national jurisdictions.

Now, in a bold and controversial move, US President Donald Trump has issued an executive order—outlined in a 2025 White House fact sheet—that bypasses this multilateral regime. The order directs US agencies to expedite seabed mining permits, effectively disregarding the ISA’s authority and the widely ratified Seabed Treaty, which the United States has never formally endorsed.

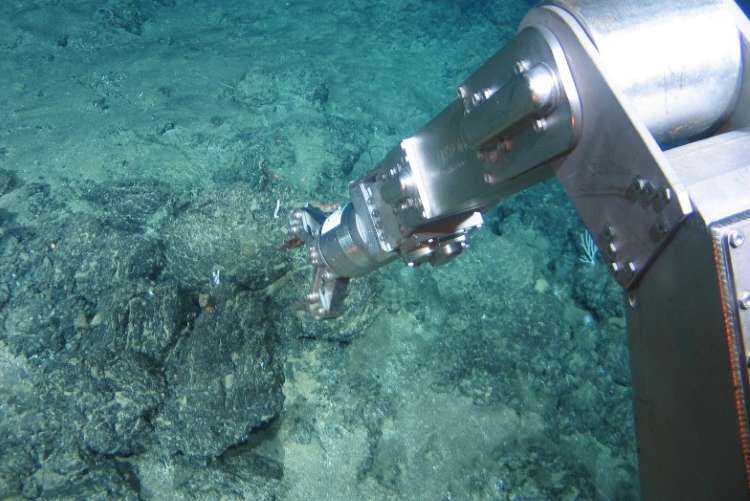

This unilateral step not only challenges the legitimacy of international ocean governance but also poses a significant threat to the ecological integrity of the Blue Pacific region, home to some of the richest untapped reserves of nickel, cobalt, copper, and rare earth elements. These deep-sea ecosystems are among the planet’s most fragile and least understood. Scientists warn that commercial mining operations here could result in irreversible harm.

READ I US-UK trade pact is more optics than opportunity

A challenge to UNCLOS and multilateralism

The executive order on deep-sea mining comes at a critical juncture for ocean governance. From April 14–25, 2025, global leaders convened in New York for the first session of the Conference of the Parties to the 2023 Agreement on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ)—a legally binding extension of UNCLOS focused on protecting marine life in the high seas.

Adopted by consensus in June 2023 and now signed by 114 countries and 21 regional parties, the BBNJ Agreement marks a historic effort to regulate human activity on the high seas through science-based and equity-driven principles. The US presidential order, in contrast, pushes aggressively toward resource extraction, without safeguards for ocean health or the rights of affected communities.

Deep-sea mining order eyes critical minerals haul

Trump’s directive seeks to cement American dominance in offshore mineral extraction, citing strategic interests and national security. It aims to accelerate US capacity for exploring, extracting, and processing deep-sea minerals, thereby reducing dependence on foreign suppliers—particularly China.

The deep-sea mining order mandates the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to fast-track permits for mining in both international waters and the US Outer Continental Shelf. It also instructs the Secretary of Commerce to streamline approvals under the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act, fostering private-sector investment and exploration.

To facilitate this agenda, the administration is mobilising a wide range of institutions—including the International Development Finance Corporation, the Export-Import Bank, and the US Trade and Development Agency—to offer financial support for domestic and international mining ventures.

National security framed as ocean control

In a further assertion of strategic priorities, the order links critical mineral extraction to US defence readiness, suggesting the use of the National Defence Stockpile for storing seabed-derived materials. The government plans to map high-priority seabed areas and identify minerals essential for energy, infrastructure, and military needs.

This policy essentially removes regulatory guardrails, creating a permissive environment for industrial-scale mining. The potential consequences—loss of biodiversity, habitat destruction, carbon release from disturbed sediments, and disruption of oceanic nutrient cycles—are scarcely acknowledged.

The Blue Pacific’s alternative vision

The Blue Pacific Continent, an idea championed by Pacific Island nations, offers a diametrically opposite vision rooted in Indigenous stewardship, cultural identity, and intergenerational responsibility. With rising sea levels, biodiversity loss, and increasing socio-economic precarity, the Pacific nations have emerged as global leaders in advocating for a sustainable and just ocean regime.

Through regional frameworks like the 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent and the Pacific Ocean-Climate Action Plan, these countries emphasise equity, conservation, and resilience. They are calling for climate financing, legal reforms, and partnerships that amplify Pacific voices and traditional knowledge systems.

This approach offers a rights-based, participatory model of governance—a sharp contrast to unilateral, extractive policies that serve narrow geopolitical aims.

A race that ignores planetary health

At its core, the executive order on deep-sea mining is a declaration of intent to industrialise the ocean floor, despite scientific consensus that the long-term risks far outweigh the short-term economic gains. Unilateral action in this sensitive domain undermines decades of multilateral progress and threatens to derail the momentum generated by the BBNJ and other sustainability pacts.

Anthropogenic stress on the ocean has already reached alarming levels. From acidification and warming to plastic pollution and overfishing, the marine environment is approaching a tipping point. Deep-sea mining, conducted without robust global oversight, could push it over the edge.

The Trump administration’s push for seabed mineral supremacy might benefit U.S. industries in the short run, but it does so by sacrificing the long-term health of the planet, disregarding global consensus, and weakening institutional frameworks built to safeguard the ocean commons.

The international community must now decide whether it will allow strategic rivalry and resource nationalism to define ocean governance—or defend the ocean as a shared heritage of humankind. That means reaffirming the principles of equity, precaution, transparency, and collective stewardship enshrined in UNCLOS.

It also means backing Pacific leadership, empowering Small Island Developing States (SIDS), and supporting new legal and financial mechanisms that put planetary health and human well-being at the centre of policy.

Because protecting the ocean is not just about protecting biodiversity—it is about protecting humanity’s future.