At the UN General Assembly in New York, a landmark agreement was struck between Unitaid, the Clinton Health Access Initiative, and Wits RHI to make the HIV prevention drug lenacapavir globally accessible. Under this arrangement, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories will produce generic versions, while the Gates Foundation will fund Hetero Drugs with volume guarantees to lower costs. The outcome could be transformative: a reduction in annual treatment cost from $28,000 to just $40 per patient, enabling affordable prevention for millions across more than 100 countries starting in 2027.

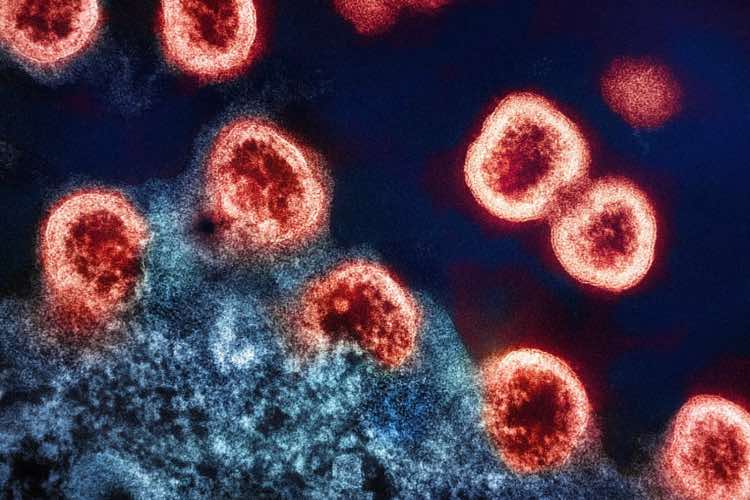

The twice-yearly injectable lenacapavir, approved by the US FDA and endorsed by both the WHO and European Commission, marks a new era in HIV prevention. Long-acting injectables could overcome adherence challenges associated with daily medication, offering near-complete protection to high-risk populations.

READ | Menstrual leave is a partial remedy, not a panacea

India’s role in generic medicines

India’s pharmaceutical industry—often dubbed the pharmacy of the world — has once again emerged at the forefront of global public health. The country accounts for about 20% of global generic medicine exports and supplies over 80% of antiretroviral drugs used in developing countries. In FY2025, India’s pharma exports reached $30.5 billion, with projections to double by 2030. Its major markets include the US, UK, South Africa, and Brazil.

India’s dominance stems from a robust ecosystem of innovation and affordability. The 1970 Patents Act, which allowed process patents, enabled Indian firms to reverse-engineer expensive drugs and produce affordable versions. Institutions like NIPER, combined with a large scientific workforce and government incentives for R&D and exports, have strengthened India’s global position. With more US FDA-approved plants than any country outside the US, India produces over 60,000 generic brands across 60 therapeutic areas, ensuring quality and scale.

Yet, the industry’s success faces new headwinds. The US FDA has increased inspections, tightening compliance norms. Supply chain disruptions and dependence on Chinese active ingredients expose vulnerabilities that India must address through domestic API parks and production-linked incentives. Without such course correction, the country’s cost advantage may erode.

HIV prevention and the Indian advantage

The latest initiative builds on a long-standing partnership between global health organisations and Indian manufacturers. In 2024, Gilead Sciences signed voluntary licensing agreements with six generic producers — including Dr. Reddy’s and Hetero — to supply low-cost lenacapavir to 120 low- and middle-income countries. Such collaborations accelerate access to new prevention tools, eliminating the years-long lag between innovation and availability in poorer nations.

The affordability of Indian generics has transformed HIV from a fatal illness into a manageable condition. Widespread access to affordable antiretrovirals (ARVs) has boosted viral suppression rates, sharply reducing new infections and AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS data show that 1.3 million people contracted HIV in 2024 — three times the 2025 target — and warns infections could reach 6.6 million by 2029 without renewed funding and innovation.

Global health impact and funding challenges

The success of lenacapavir could significantly alter the trajectory of the epidemic, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where the burden remains highest. South Africa, with under 1% of the world’s population, accounts for nearly 20% of people living with HIV. Despite wide coverage of oral preventive therapy, adherence challenges persist. A biannual injection could close this gap, but rollout challenges remain.

Global health agencies plan to reach 2 million people initially, though experts estimate at least 10 million must receive the drug to meaningfully impact transmission. Funding constraints pose a serious risk—especially as the Trump administration considers limiting financial support to specific groups such as pregnant and breastfeeding women. Without sustained investment, even the most effective innovations may fall short of their potential.

India itself continues to face one of Asia’s largest HIV burdens, with about 2.4 million people living with the virus. Integrating new prevention tools like lenacapavir into India’s national AIDS control programme could dramatically improve adherence rates and reduce infections, particularly among high-risk urban and migrant populations.

India’s opportunity in global health diplomacy

India’s capacity to manufacture affordable generics has not only transformed health outcomes but also bolstered its global standing. From HIV/AIDS to tuberculosis and malaria, Indian pharmaceuticals have been instrumental in scaling public health interventions across the Global South. Yet, despite these achievements, India lacks a coherent health diplomacy strategy that leverages its pharmaceutical prowess for geopolitical and developmental advantage.

Developing such a strategy would allow India to consolidate its leadership as a reliable supplier of affordable medicines, negotiate better terms in global health governance, and ensure equitable access for low-income countries. This is particularly urgent as stricter patent regimes, API dependence on China, and tightening regulatory norms threaten the competitiveness of Indian generics.

READ | Menstrual leave is a partial remedy, not a panacea

Sustaining innovation and access

The future of the global HIV response hinges on maintaining policy space for generic production and encouraging innovation that prioritises public health over profit. India must expand its investments in biotech research, ensure supply-chain resilience, and push for global frameworks that recognise the legitimacy of compulsory licensing and voluntary technology transfer.

Global access to generic medicines will also hinge on the outcome of ongoing WTO negotiations over TRIPS waivers for essential drugs. India and South Africa have argued for broader IP flexibilities to cover HIV prevention medicines — an agenda that could define the next phase of global health equity.

Access to generic medicines — driven largely by India’s pharmaceutical ecosystem — has turned ambitious goals like ending AIDS as a public health threat by 2030 into realistic possibilities. The next frontier lies in long-acting therapies like lenacapavir. If India aligns its industrial strength with strategic diplomacy, it can secure its place not just as the world’s medicine maker, but as a pillar of global health equity.