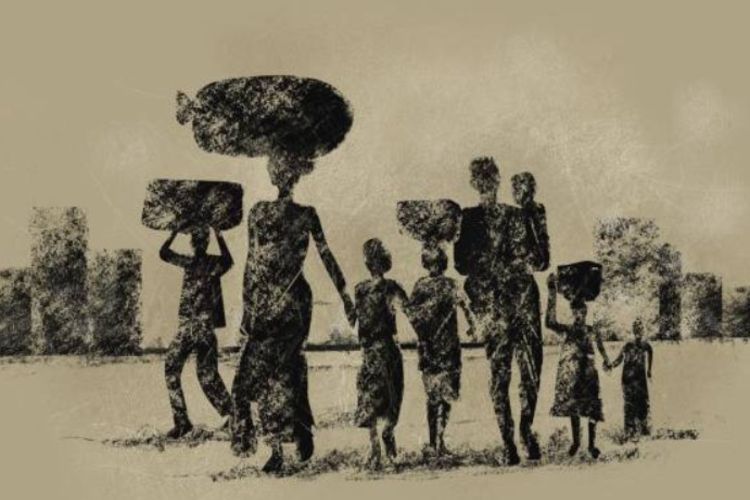

Migrant workers power India’s factories, construction sites, farms, transport hubs, and digital platforms. They form a large share of both the organised and unorganised labour markets, yet the country still lacks an accurate and contemporary understanding of who migrates, why they move, and how mobility shapes their lives. Much of the official thinking rests on outdated data from a very different India — one without smartphones, job apps, or platform work.

The ministry of statistics and programme implementation seeks to change this. It has announced a comprehensive National Migration Survey for 2026–27, a long-overdue attempt to update the evidence base for labour, welfare, and urban policies. Until now, policymakers have relied on decennial Census figures and occasional migration modules in National Sample Survey rounds. These datasets have been too coarse to capture the insecure and circular mobility patterns that now define India’s workforce.

READ | Urban homelessness exposes deep policy failures

The stakes are high. Every major reform, from labour codes and social protection schemes to urban planning and welfare portability, depends on an accurate picture of migrant movement. The pandemic made the gaps stark. Millions walked hundreds of kilometres because the state did not know where they lived, worked, or earned. When data is missing, policy operates in a vacuum.

Urban migration trends and gender gaps

Recent surveys underline how migration has changed. The NSS Multiple Indicator Survey 2020–21 reports that nearly three in 10 Indians are migrants, rising to 34.6% in urban India. Women still dominate migration counts due to marriage-related moves. But male migrants tell a different story: one in two moved for employment, signalling deep labour-market frictions in home states.

Yet focusing only on marriage migration obscures a structural shift. Women are increasingly migrating for work, not just for family reasons. PLFS data shows rising female mobility linked to domestic work, food processing, garments, and electronics manufacturing, especially in southern and western states. These jobs offer income but little safety. Workers often live in cramped dormitories, lack secure housing, and face high vulnerability to harassment. This shift signals the feminisation of labour migration, a trend the new survey must capture with clarity.

Migration remains highly local. Most people move within their district or state. Yet work-related migration shows a different trend—40% of employment-related mobility is inter-state, compared to just 5% for marriage-related movement. Sharp variations in job opportunities across states continue to shape these flows. States with limited industrialisation or chronic rural distress send far more workers out than they receive.

What official data misses

Official statistics fail to capture the rhythms of modern labour mobility. Research by India Migration Now, the International Labour Organisation (ILO), and state labour departments shows that temporary and circular migrants form the backbone of construction, logistics, hospitality, and seasonal agriculture. Their work spells—15 days on a site, two months in a warehouse, three weeks in a factory—do not fit older survey definitions. Many underreport hardship or insecurity, further deepening the data gap.

Migration also reflects India’s uneven development. Kerala, Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Telangana attract migrant workers due to stronger job markets and deeper urbanisation. Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Odisha remain major sending states—a pattern entrenched over generations, not decades. The recent Bihar election cycle brought this issue back into public debate, as parties acknowledged that workers migrate not for aspiration but survival.

The new survey proposes a critical update: redefining short-term migration to include spells of 15 days to under six months. This aligns with how workers actually move today. Another key feature is categorising households by remittance dependence. For states like Bihar, Jharkhand, and Odisha, remittances act as a de facto welfare system—sustaining consumption, financing education, and enabling asset creation. Yet India currently relies on fragmented state surveys and scattered academic studies to understand this essential flow.

From counting migrants to tracking outcomes

The most important innovation is conceptual. For the first time, migrants will be asked not just why they moved, but what happened after they moved. Did incomes rise? Did access to housing, healthcare, or education improve? Did mobility enhance opportunities or deepen precarity? Did they face discrimination or unsafe working conditions?

This brings India closer to global best practice. Countries such as Mexico, the Philippines, and Indonesia run regular migration surveys that track earnings, family separation, wellbeing, and long-term outcomes. The World Bank’s KNOMAD initiative has repeatedly emphasised that outcome-based data is the foundation of sound migration governance.

Why better data matters for policy

Accurate migration data can reshape policymaking in three critical ways. First, it can improve labour protections. Current laws categorise workers by job type, not mobility pattern. Better data could help tailor social security to those who move frequently across states and sectors.

Second, it can guide urban planning. Migrants often live in informal settlements with limited access to water, sanitation, or healthcare. Data on seasonal surges can help cities plan infrastructure and services more efficiently. Third, it can strengthen welfare portability. Despite progress under One Nation, One Ration Card, millions still fall through cracks because social protection remains tied to place of residence. Good data can help design truly portable benefits.

Social security for a mobile workforce

India’s social protection architecture remains designed for a workforce that stays in one place. Migrant workers fall outside almost every formal safety net. The e-Shram portal has registered around 290 million workers, but registration alone has not translated into secure benefits. Coverage under ESIC and EPFO remains thin for workers who shift employers or worksites rapidly.

Maternity benefits, accident insurance, and health coverage rarely travel across state boundaries. Most welfare systems still assume stable employment relationships—conditions that simply do not exist in construction, logistics, domestic work, or gig employment. Without redesigning social protection around mobility, millions will continue to work without meaningful security.

Administrative capacity and survey’s success

The ambition of a comprehensive migration survey is commendable, but its success hinges on execution. Survey capacity has weakened over the years as the NSS network grapples with staffing gaps and inconsistent training. Migrants often work night shifts, live in temporary settlements, or move frequently—making them difficult to enumerate.

Field capacity varies widely across states; Kerala and Maharashtra may produce high-quality data, while poorer states may struggle to track even basic indicators. Effective coordination across ministries and better-resourced field teams will determine whether the survey can correct old blind spots or merely reproduce them.

Migration is not a marginal issue. It is central to India’s growth story—from construction and logistics to festival-season manufacturing and digital platforms. Yet migrants remain poorly documented and weakly protected. The upcoming National Migration Survey cannot solve every challenge, but it can offer something India has lacked for decades: a clear, modern, and outcome-oriented picture of mobility.

India’s economic engine relies on the movement of people. It is time national policy recognised them not as temporary populations but as workers, contributors, and citizens whose mobility keeps the economy running. A robust migration survey is the first step towards that overdue recognition.