India is quietly scripting a revolution in its agricultural sector—one not driven by new seeds or subsidies, but by satellites. In a country where farming still sustains nearly 40% of the workforce and anchors food security for over a billion people, the shift from hand-drawn crop maps to high-resolution geospatial imaging marks a structural inflection point. By embracing emerging technologies such as satellite imagery, AI-powered analytics, and open data platforms, India is laying the groundwork for a more resilient, efficient, and data-driven agricultural economy—one that could redefine how food is grown, financed, and insured in the developing world.

India has already taken the first definitive steps on this journey. In a significant departure from tradition, the first advance estimates for kharif crop acreage this year—expected in September—will be based not on manual surveys but on satellite data. This marks the beginning of the end for the age-old girdawari system, in which village-level revenue officers recorded crop data by physically visiting farmlands. In its place, a high-precision, digitised approach is being ushered in—one that promises more accuracy, efficiency, and sustainability in agricultural production.

READ I Social security net grows, but gaps remain

Ending the manual girdawari

The ministry of agriculture and farmers’ welfare will soon release its first fully digitised kharif crop acreage estimates. This shift is not symbolic—it represents a tangible break from legacy practices. According to pilot studies, the satellite-based method delivers 93-95% accuracy, offering a far more reliable foundation for policymaking and planning than manual estimates ever could.

The transformation is most visible in states like Uttar Pradesh, which has emerged as a testbed for agritech-driven reforms. Supported by the International Finance Corporation, the AgriStack programme in the state seeks to digitise farm credit processes for nearly 80 million farmers. As part of the push, government APIs now allow private players access to digitised land records and geospatial farm boundaries—laying the groundwork for a data-rich ecosystem.

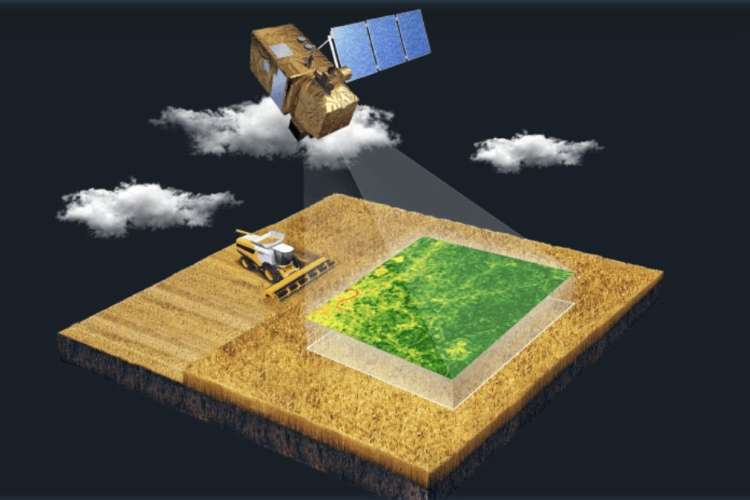

Startups such as Bengaluru-based SatSure are deploying satellite imagery combined with artificial intelligence to detect crop types, monitor plant health, and evaluate climate conditions. These insights generate farm-level risk scores, which are now being used by banks like ICICI and HDFC to assess creditworthiness and income potential of borrowers. Similarly, Hyderabad’s Dhruva Space offers high-resolution imagery through its AstraView platform for improved operational and environmental assessments. Another player, Pixxel, is revolutionising rural banking by enabling hyper-local, real-time assessments that help redesign insurance products and make agricultural lending smarter and more inclusive.

Mapping risk from space

The integration of satellite data—sourced from open platforms like the European Space Agency’s Copernicus and ISRO’s Bhuvan portal—has helped streamline critical agricultural processes. For banks, this means that farm-level risk reports can be instantly generated by simply entering a land parcel’s location. This shift has significantly reduced loan processing times, improved service delivery to farmers, and strengthened the rural credit architecture.

Globally, too, the promise of satellite-based agriculture is gaining recognition. UNCTAD has underlined the value of such technologies in developing countries, where modernisation of agriculture is not just about economic growth but about survival. The transition from traditional to tech-enabled systems represents a major leap forward.

The girdawari system—despite being institutionalised over decades—has serious limitations. It is labour-intensive, time-consuming, prone to human error, and, most importantly, not reflective of India’s evolving agricultural trends. It largely covers the 25-26 major kharif crops—rice, maize, jowar among them—but fails to capture the growing acreage of newer, high-value crops like berries, avocados, and dragon fruit, which are increasingly favoured by farmers diversifying their income sources.

Satellite-based approaches resolve many of these problems. Real-time, high-resolution data allows for dynamic mapping of crops with far greater accuracy and speed. This, in turn, results in more accurate agricultural statistics, fewer post-facto revisions, and more stable policy frameworks. The ministry of agriculture’s efforts through the digital crop survey, in collaboration with state governments, aim to build on this momentum.

Satellite imagery and precision agriculture

Precision agriculture stands to gain significantly from satellite imaging. It enables better tracking of crop health, soil conditions, and yield forecasts, ultimately improving input use efficiency. By reducing waste and improving productivity, it lays the foundation for sustainable farming.

Importantly, satellite imagery can also help farmers prepare for a rapidly changing climate. As UNCTAD has noted, the technology enables better weather prediction, smarter irrigation scheduling, and early identification of pest infestations or nutrient deficiencies. These insights are crucial for timely interventions, especially in drought-prone or ecologically fragile regions. For India—among the countries most vulnerable to climate change—this could be a game-changer.

India’s early experiments have already delivered promising results. During the kharif season of 2024, states like Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat successfully piloted the use of satellite data, achieving notable improvements. The DCS now covers all districts in these states, with recorded increases in reported acreage—especially for rice. These pilot successes provide a template for national roll-out and for other developing nations to emulate.

Challenges of scale

However, modernising agriculture through satellite tech will not be without its challenges. Infrastructure gaps, particularly in rural connectivity and digital literacy, remain major hurdles. Many farmers lack access to internet services or digital devices that can translate satellite insights into actionable decisions.

Data security is another emerging concern—without strong privacy safeguards and equitable access, there’s a risk that only large agribusinesses and intermediaries will benefit. The government must work with international organisations and civil society to ensure these digital tools empower, rather than exploit, small and marginal farmers.

In a world of eight billion people, feeding everyone sustainably will require nothing short of a technological transformation in agriculture. For countries like India, this means moving beyond legacy systems to embrace innovation with urgency and resolve.

The shift to satellite-based agriculture is not just a technical upgrade—it is a strategic necessity. India’s proactive embrace of this transformation offers a compelling model for the Global South, proving that even traditional sectors can be reshaped through the intelligent application of data, science, and state support.